The Sanskrit word ANAHATA roughly translates to unhurt and unbeaten. In its contemporary usage, it speaks to a life of experience unhindered by the burdens of egotism and indulgence. At James Oliver Gallery, the exhibit which bears this name shudders with motion, distorts the human form, and celebrates a life lived deeply and authentically, in digital photo compositions by John Singletary. A companion show by designer Bela Shehu presents experimental clothing constructed with industrial-grade Tyvek. Both artists are interested in forms of healing, but their divergent approaches yield a dynamic exchange.

Singletary, a Philadelphia artist acting as director and photographer transports viewers away from the egocentric and perceptible by thrusting them into the fray of the unconscious mind where emotion and motive give way to raw understanding. In his incursion against the boundaries between the inner self and the rest of existence, Singletary’s black and white images, site-specific setting, and accompanying musical score work to broaden the narrow perspectives that tend to rule our prosaic routines. Philadelphia designer Bela Shehu’s new NINObrand clothing line entitled “I Forgive You,” made entirely from Tyvek, stands in contrast to Singletary’s ethereal vision, and delves into personal and social lamentations by way of her physical fabrications.

A sanctuary of movement

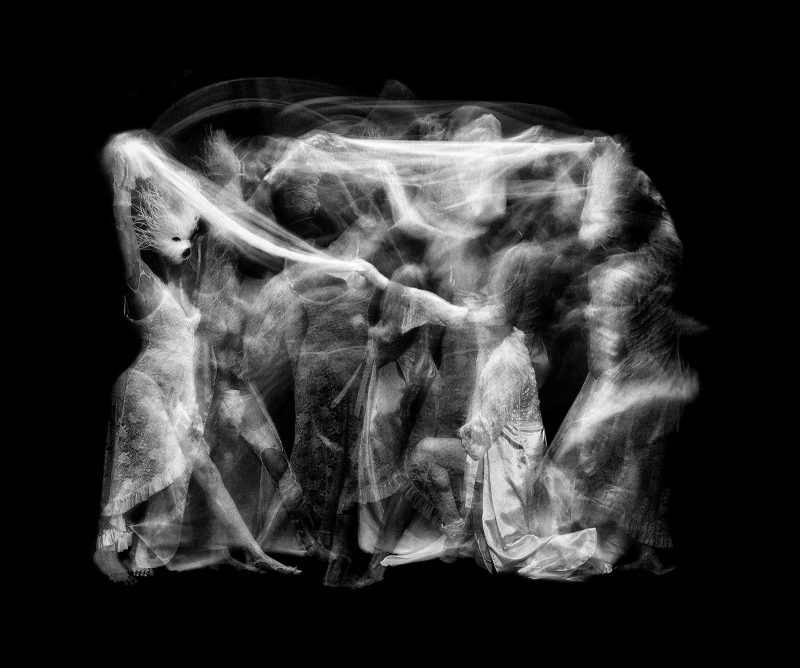

Visitors to the gallery are immediately made to confront a wall of blackout curtains draped across the width of the entire room. Inside this sanctum, Singletary has arranged over a dozen flat, LED monitors against the dark, fabric-draped walls. These screens feature theatrical images depicting costumed dancers coated with reflective UV paint and fabrics in narrative tableaus. The artist has digitally layered any number of discrete shots into one still image of a flurry of movement. Although some of the photos shine forth from only one monitor, others exist as a compilation of multiple frames pieced together to produce a single image. Each individual work is set on its own time interval as it slowly brightens to white before the picture flashes away, leaving only an empty, black screen. Gradually, the photos fade back into view, as if they had never disappeared. The resulting effect bestows each scene with a pulsing spirit or life of its own.

A true theurgy is taking place here as the shamanistic dance rituals that Singletary captures with his camera parallel the hypnotic atmosphere of the gently shifting gleam of the monitors. Instead of reflecting ambient light as with a printed photograph (or radiant, painted dancers and their outfits), these LED images glow with their own luminosity, producing a closed environment within the curtains instead of relying on inputs from beyond the installation.

Everything here observes a sort of rhythm, echoing the universe at large, but also indicating our innate capacity for pattern recognition. As the screens shine forth and dissolve, the hazy actions of the figures that reside therein create an ebb and flow independent of the light show as they return to view. In many frames, the bodies resemble spirits more than living beings. This is most clear in “The Dance of Hades,” where Singletary exchanges the corporeal for a cyclical flow of pure energy, as the dancer seem connected more by light itself than one another. In this piece, the human form presents itself as an addendum to the fundamental components of the cosmos, and the activity is more concerned with physics than human will.

Despite the apparent mantra of connectedness, the enshrouded room seems paradoxically sealed and shut off since it is imbued with its own light, sound, and action, much like the artworks themselves. After spending enough time inside this refuge, the rest of the world – full of its myriad people, problems, and splendors – appears to retreat and diminish.

In “Clarise,” a woman sits alone amidst a cyclone of twisted, goblin-like creatures who are held at bay as she manifests a beam of energy from her raised palms. She dwells in this oasis of her own making much as ANAHATA provides sanctuary for visitors to the gallery. Her feather-covered body is soft and delicate in the midst of this tempest, and strongly at odds with the ogrish beings whose twisted faces taunt but fail to reach her. This steadfast and supernatural act of resilience offers us optimism for confronting a confusing and sometimes hostile world.

Past, present, and future as a surrounding forest

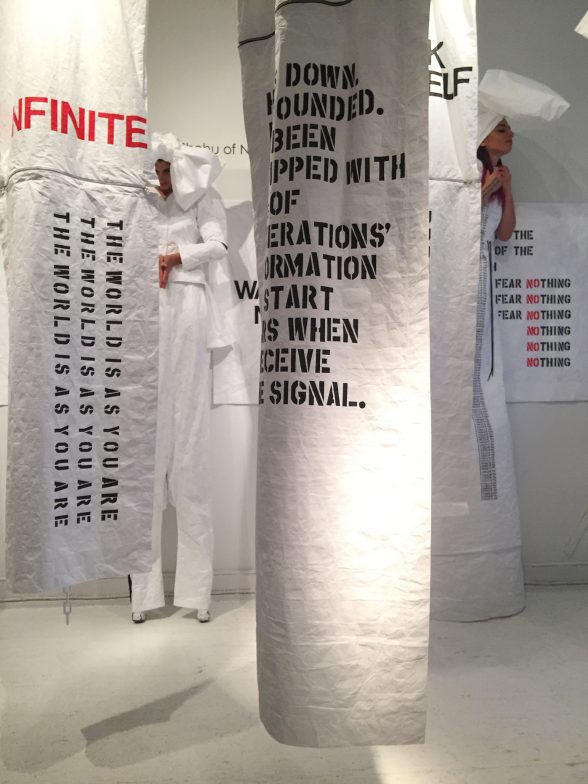

Stepping outside the protection of ANAHATA, Shehu’s garments serve to quickly ground us again. The white dresses dangling from chains on the ceiling are unmistakably tangible compared to the radiant imagery of Singletary’s incorporeal show, and, measuring some eight feet tall from top to bottom, are far too long and cumbersome to wear, emphasizing their physicality. Models at the opening, however, donned stilts in order to endure the unwieldy outfits. Additional ready-to-wear versions made specifically for the exhibition were also available for purchase on a rack across the room from the display.

Tyvek, used in building insulation, shipping, and other industrial applications, is Shehu’s material of choice here. Possessing a waxy, somewhat rigid texture, comfort is clearly not a primary concern for these costumes, even aside from their scale. The sterile, papery apparel is more indicative of a medical or hazmat outfit, or even more unsettlingly, a prisoner uniform.

Printed text lines the otherwise blank attire, reading as much like a personal journal as a means of reassurance for others. Many fears are asserted and assuaged on the surface of these creations: “Fear Nothing,” “Want Nothing,” “Love & Brilliance,” among other phrases, are prominently featured in red and black against the white fields, alongside more extensive passages as well.

The primary messages here deal with acceptance, freedom, and forgiveness. “Dear Ancestors, I forgive you” resonates not only because it contains the title of the exhibit, but mostly because it repeats the second phrase some forty times over down the back of a single dress. We find ourselves steeped in transgressions of the past, uncertainties of the future, and the all-encompassing dilemma of the present moment. The stilt-walking models represent precarious harbingers of the perilous historical moment we inhabit, and they bear the pronouncements of our collective experience boldly for all to see.

Bela Shehu encourages us to speak truth to power, to reclaim unity, and to offer forgiveness across the board, while John Singletary cracks open the inner space of our psyche and taps into the universal cadence that links us all. Each artist represents alternatives to familiar perceptions by either transforming the most outward, stylistic elements of our identities or through reconsidering more hidden, intrinsic qualities of nature. Surely there is no definite path to take in our journey, but each of these artist blazes a trail for us to explore.

ANAHATA is up at James Oliver Gallery, 723 Chestnut Street 4th Floor, until June 9th.