Nkame

Nkame, the retrospective of Cuban artist Belkis Ayón’s work at El Museo Del Barrio, is a visually striking, poignant survey of the artist’s prolific although short career. Ayón’s stylized and androgynous humans compel you to look as they stare back at you in ambiguous tableaus that suggest rituals and smoldering disputes. I confess that I didn’t know much about the artist before this show, but the ambiguity of the subject as well as the blunt, dynamic style of her work, printed in a grouping of inky black collography prints and collaged together into mural-sized pieces, immediately drew me in.

The exhibit, which covers the majority of Ayón’s career, from 1986 when she began art school until her suicide in 1999, shows the artist’s focus was on stories from the founding myth of the male-only, Afro-Cuban Abakuá secret society and particularly, on illustrating the story of the sole female figure in the myth, Princess Sikán.** (see end note). Ayón intended her work as allegorical commentary on contemporary issues of gender in Cuba, and in that respect the work speaks loudly to today’s discussions of gender parity and tolerance of gender non-conformity. She is quoted on her estate’s website as saying in 1998, close to her death, “Sikán’s image is paramount in all these works because, like myself, she led and leads –through me-, a disquieting life, looking insistently for a way out.”

Perfidia

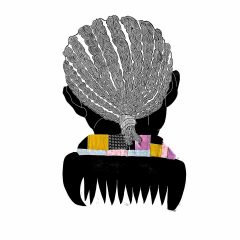

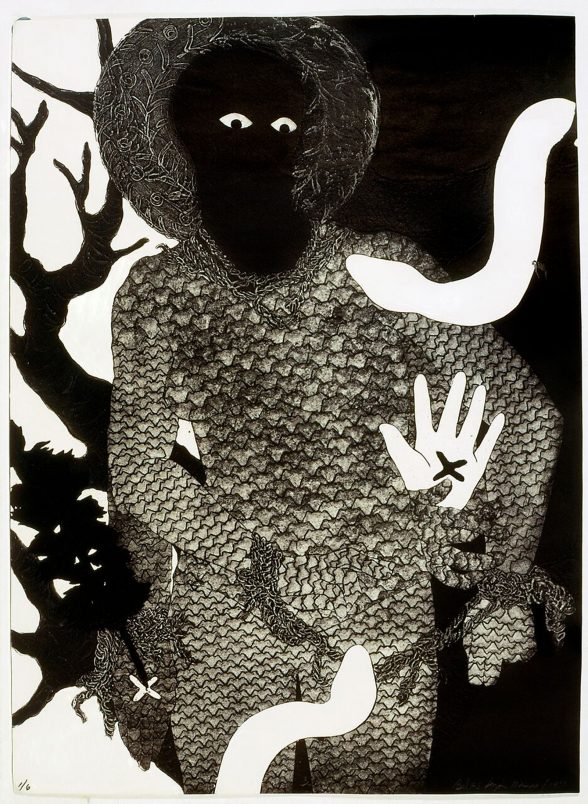

Princess Sikán’s story is a cautionary tale illustrating the perfidy and disobedience of women and establishing the basis for their exclusion from the Abakuá society. Princess Sikán finds a supernatural fish and is instructed by her male elders not to tell anyone about her discovery. Instead, the Princess tells her lover, Prince Mokongo from the neighboring kingdom, and provokes a war as her prince raises an army to take the fish by force. Although the two nations eventually sign a treaty and agree to jointly venerate the fish, Sikán is sentenced to beheading for revealing the secret. Ayón’s piece,“Perfidia,” illustrates the latter part of this story in an image of Baroque-level theatrical drama. On one side of the diptych, a high-ranking official reports to her father the news of Sikán’s transgression. The mystic who negotiated for peace stands holding a rooster, a symbol of ritualistic sacrifice. To the left stands Sikán, simultaneously shown from the front and back. She is covered in fish scales, a reminder of her disobedience that brings to mind “The Scarlet Letter” or perhaps the betrayal of Jesus by Judas. In contrast to all other figures, the princess’s skin is white — in Abakuá lore an indication of her imminent death. All eyes and hands point to her accusingly, and from behind she holds the sacred fish in one hand. The image is dynamic, unnerving, and truly showcases Ayón’s mastery of not only collography but also narrative.

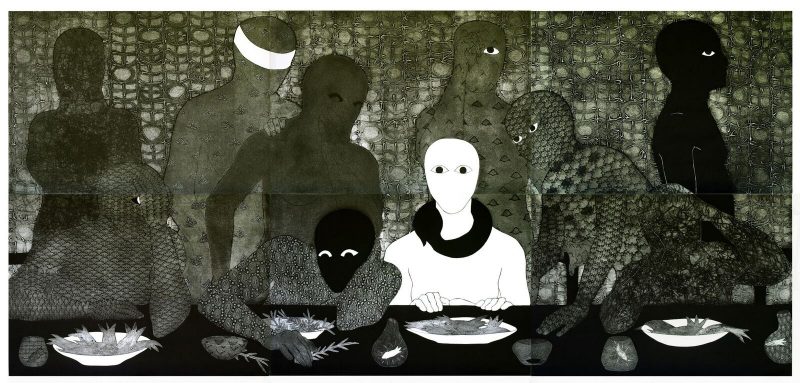

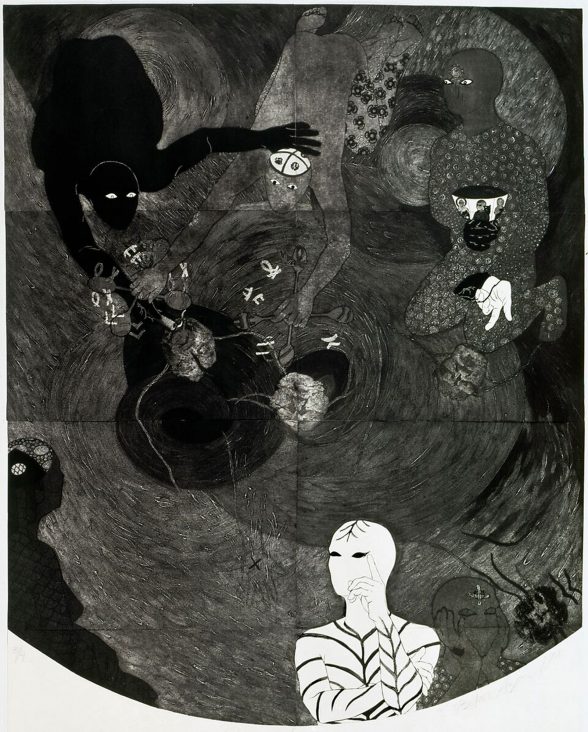

La Cena

One of the first artworks visitors notice when entering the gallery, “La Cena,” is a great example of Ayón’s ability to weave complex narrative with a complicated printing process. For Western eyes, the visual clearly references the last supper of Christ. The wall text explains that this is also an allusion to the initiation feast of Abakuá. Upon closer examination, you notice that the major participants in the image are women, in contrast to the reference materials for the scene in Abakuá and the Christian religions, that were both almost exclusively male. Sikán sits in the center, taking the role of either Christ or the initiation leader depending on your perspective. Using collography, Ayón creates a beautiful variety of texture and saturation in grayscale. The stylized depiction of human silhouettes that Ayón is known for are featureless aside from wide, unblinking eyes and suggest one who sees all but is silenced; Sikán plays a central role in her work as a woman who gains knowledge forbidden to her, a woman who disobeys, and a woman who is punished. Sikán’s is a very human story of someone who made a mistake and was disproportionately punished for it.

Influences

Ayón’s art touches on three important elements of Afro-Cuban (and generally Afro-Latinx) life: the simultaneous influence of a person’s ethnic and cultural roots and nationality; the give and take of that ethnic history with Christianity and Catholicism; and the gender dynamics that weave through it all. The Abakuá mythology that the artist co-opted illustrates the complexity of these factors at play and, on a darker level, the struggle to stay afloat while navigating it all. Ayón’s art is beautiful, complex, and above all unsettlingly grim and relentless.

End Note

The Abakuá association’s roots are in Nigeria and Cameroon, in the religions of ancestors brought over in the transatlantic slave trade. It is sometimes compared to Freemasonry due to its secrecy and exclusive initiation, but Abakuá is also a syncretic religion. The Abakuá today continue to practice their religion in Cuba; the religion has its own language, and religious garb, music, and dance are said to be major elements of their worship. Fascinatingly, two of the most well known music genres to originate in Cuba, son and rumba, were created and pioneered by Abakuá members taking heavy inspiration from the music used in ceremonies.

Nkame is on view at El Museo Del Barrio, 1230 5th Ave, New York, NY until November 5th.