Getting lost

I spent two days in Kassel in June wandering, getting lost and feeling pretty much like an unwanted person. I don’t know for sure, but figured my frustrations (lack of German, bad maps, generally unhelpful printed materials) were probably intended to give me, an art lover empowered enough to visit Kassel, a meta-experience of (temporary) displacement and lack of power. My sample size is small but I talked with other non-Kassel-based art lovers who expressed the same frustration and also wondered about whether it coincided with curatorial intent. Regardless, the experience of getting lost at Documenta 14 was humbling. Also, it helped me understand that a big part of the audience for Documenta is the people of Kassel, who speak the language, don’t need a map to get around, and are willing, eager and proud to partake of what their city provides for the world every five years.

The Parthenon of Books

Upon arriving at the train station and climbing into a cab, I heard from my driver, a German, who knew much about Documenta 14 and said he always went to see the art, that this was the most political year yet for the show. He excitedly told me about the big public piece, “The Parthenon of Books,” (by Marta Minujín) down in the main plaza, opposite the Fridericianum, the main Documenta museum. I dropped my bags at the hotel, hopped a tram and went looking for the Parthenon.

What I imagined — a towering temple actually made of books — turned out to be not that but an infrastructure-heavy and frankly pretty inelegant structure with books in plastic baggies pinned around the armature to evoke the look of the Parthenon. Big and full of books, it is. But, made in such a utilitarian fashion it was/is a disappointment. Then there is the location. The Parthenon of Books is not elevated on a hill, and it is placed so close to the elegant Fridericianum, that it can’t possibly compare. The placement is symbolic; it’s the place where Nazis had a big book burning in Kassel in 1933. Documenta invites you to donate your books at a small drop box next to the temple — or you can email books@documenta.de for more information. But that community project seems somewhat tacked on.

Fridericianum delivers several high points

Inside the Fridericianum, the museum that is the Documenta anchor, you get immersed in the collection of Greece’s National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST), which has been installed top-to-bottom in the Kassel museum, a warm symbolic embrace of all things contemporary and Greek. There are videos, audio works, digital projections, sculptural installations, performance — what you would expect from a museum of contemporary art situated in the West.

Notable Fridericianum moments are Stafanos Tsivopoulos’s “Precarious Archive,” an idiosyncratic 40-year research project by the artist into issues of power, corruption, and the media. The piece is as much about who owns our history as about the history itself. The archive of photos and documents is “activated” by performers wearing white gloves and continually moving things around in a way that suggests the instability of records and of the world. It’s a great piece.

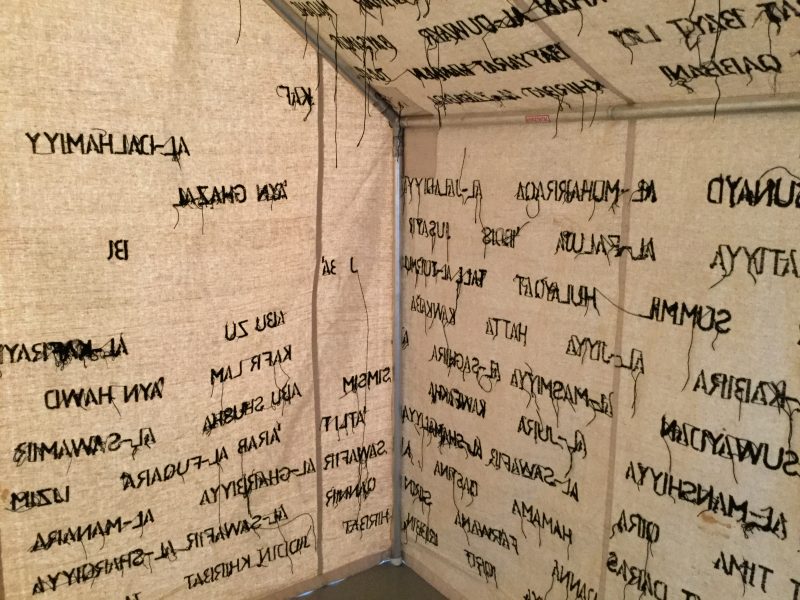

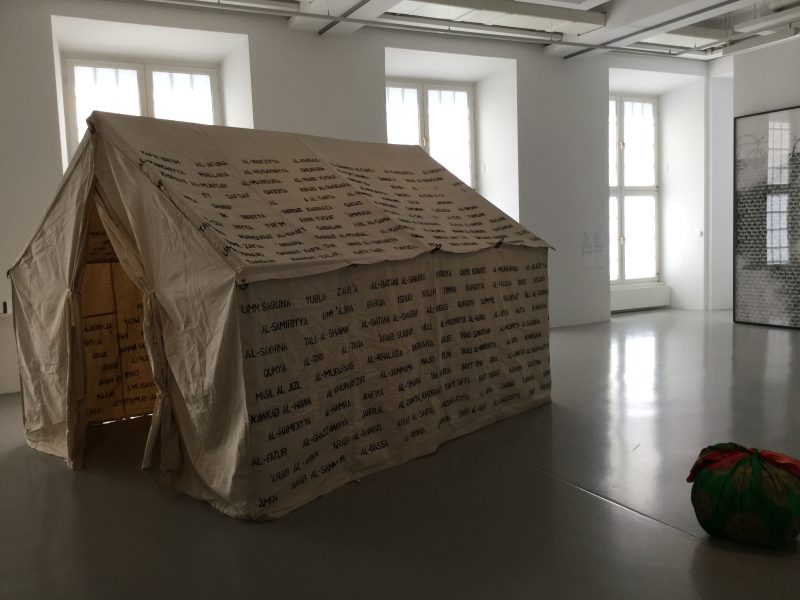

Also great is Emily Jacir’s small tent structure, which features the names of 418 Palestinian villages destroyed by Israel in 1948, names embroidered onto the tent by those who knew of the villages. Both Jacir’s and Tsivopoulos’s pieces resonate strongly with the overarching theme of Documenta 14 – power, ownership, destruction, displaced people and a feeling of harm done that needs to be redressed.

Documenta Halle’s big space with a moving and intimate work

Indigenous people, who are disenfranchised in their own lands, are richly featured in Documenta 14. The embroidered history of the world according to the reindeer herders of Sweden, for example, is a simple and complex story scroll of the hunting and herding culture that is threatened by laws that encroach on the traditions of the native peoples. The scroll, by Britta Marakatt-Labba, whose family includes reindeer herders, is intimate, wordless, and placed, unframed, at eyelevel on the wall. People walk past slowly, absorbing the visual storytelling like advancing through the Stations of the Cross.

The piece, called “Historja” (2003-07) is fierce and proud and captures the spirit of life lived close to nature. Note in the detail shots how the mode of transportation changes from sled to skis to snowmobile as you move through time.

Found with the chorus and the Kassel community

After the two big venues and feeling the need for companionship, I signed on for two walk-and-talk tours led by members of the “chorus,” specially trained guides whose role is to lead open discussions about the art. And, it was on these chorus tours that Documenta came alive for me. It’s where I found my people, those who wanted to look and talk and share and feel together about the powerful and socially-conscious art. I’ll tell you more about the chorus walks in the next post.

Meanwhile, this also happened. One of the days I was there was a state holiday, and the shops were closed and many in the Kassel community came together in Konigsplatz for an open air Catholic mass. I didn’t know it was a holiday but heard the music and saw the crowd while I was wandering, lost, looking for the venue for my first walk with the chorus. The living, breathing community-in-action moment reinforced my outsider status but made a compelling and beautiful assertion of community that was completely its own thing, not art, and I totally loved it.

Documenta 14 is open in Kassel, Germany until Sept. 17, 2017.