The small group show organized by truth-to-power ceramicist Roberto Lugo and installed in the intimate Draper Gallery at Delaware Contemporary has great art in it and is an example of art as history-telling absent the hectoring. Washed in a palpable sense of humanism, works by by Lugo, Charlie Cunningham, Yelizaveta (Liza) Masalimova, Theodore Harris and Mat Tomezsko pay homage to Emmett Till, a hero of the Civil Rights movement, and to contemporary icons of the Black Lives Matter movement like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Contemplative and memorializing, the show speaks quietly of the racial violence that is with us today. Without offering answers to the complex problems of racial hatred and societal injustice, the art, by a gender- and racially-diverse group of artists and collaborators, leads by example.

detail, “Jarring”

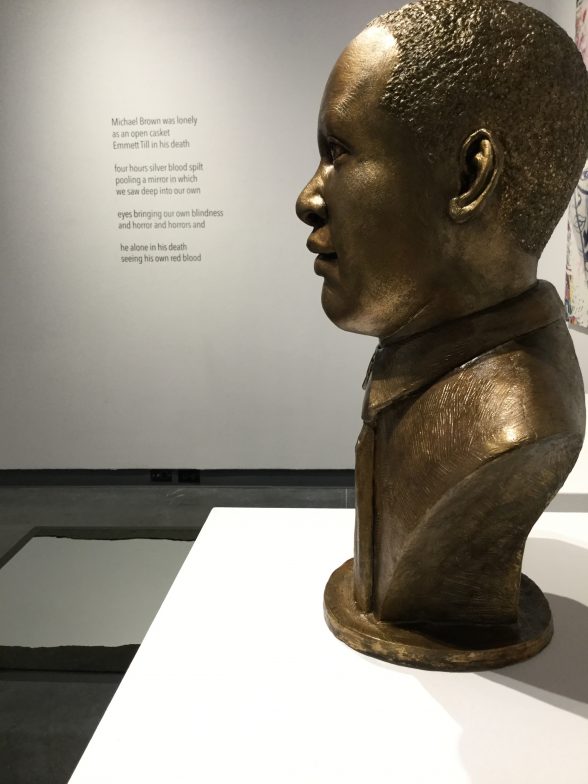

(collaboration with Roberto Lugo) cast concrete and patina. Background wall is poem from detail of Mat Tomezsko “Silver Vision”

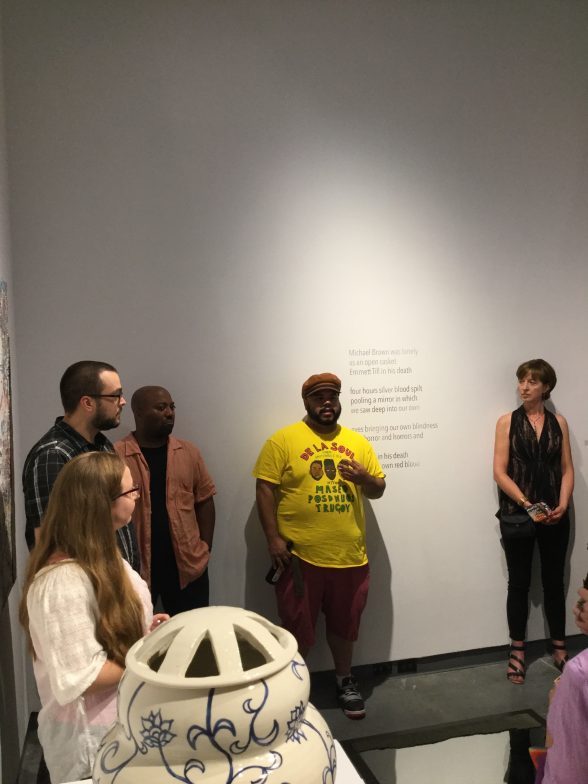

Lugo, who was honored Friday night with the prestigious Draper award, conferred each year by Delaware Contemporary, spoke passionately about the importance of community and of how the exhibit came together over time in discussions with his friends, Charlie, Liza, Mat and Theodore. At a panel the same night (I was moderator), the artists talked about memorializing lost lives, and about, as Lugo says in his curator’s statement, “the misconception that systemic and institutional racism ended during the Civil Rights Movement.”

When seeing the exhibition Friday night and hearing Lugo and the artists speak about the work I realized the great gift of this show. Like other successful public monuments or memorials to loss, Jarring, both in the individual works and as a whole, provides a needed distance from argument and a space for contemplation.

Art is slow and takes time to make. Through time, artists create something that reflects their thinking over time, a process that evolves from a snapshot to deeper picture of emotion coupled with decisions wed to materials. Unlike the flashpoint, stuffed-animal-and-candle memorials on the streets, slow art takes a step back from the heat and invites — not tears or rage — but thoughts of our common humanity.

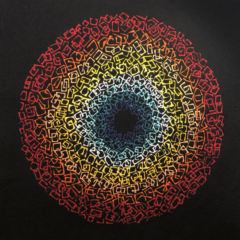

Many memorials in the public realm are statues. Statues work because they embody the physical human, which all of us look for in art (how this searching for the human relates to abstract art is for discussion another day). In this show, in the collaborative work “Jarring” by Lugo and Charlie Cunningham, there is a bust of Emmett Till, placed almost at eye level, and nearby, an urn/jar with Till’s beautiful smiling face painted on. You can have a deep encounter with the Emmett Till this way in the quiet gallery and there is space for all thoughts about race and violence to occur in the neutral white-walled space. In another collaborative piece Yelizaveta Masalimova’s hoodie-wearing statue of Trayvon Martin and a ceramic face mask of the youth, visible through the apertures in the lid of the jar created by Lugo, provide a moment of spooky contact with the more recent victim of racial violence. Matt Tomezsko’s installation, which is abstract and conceptual, provides a mirror for people to literally be involved in this history. And Theodore Harris’s collage works, which invite close scrutiny, invoke thoughts of politics and needed legislative change to protect people instead of oppress them.

Art has always told history. But, art’s history paintings and memorials generally have told the story of those who have commissioned the works, generally the powered and monied class, which wants to tell heroic stories of battles won and champions they want heralded. What is urgent today more than ever is for art and artists to tell their stories, stories important to all people and that create a truer — and less glorious and more painful — picture of our world.

Jarring, up to Aug. 27, Draper Gallery, The Delaware Contemporary.