Telling Stories

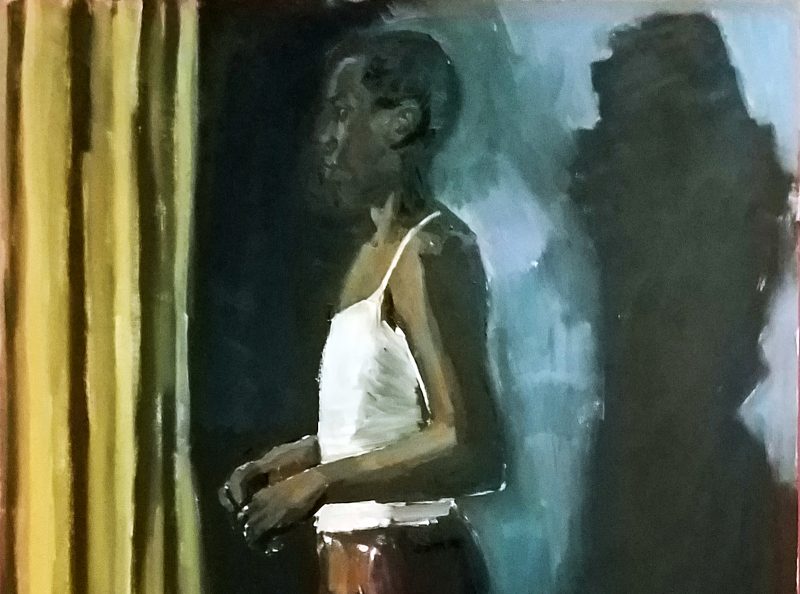

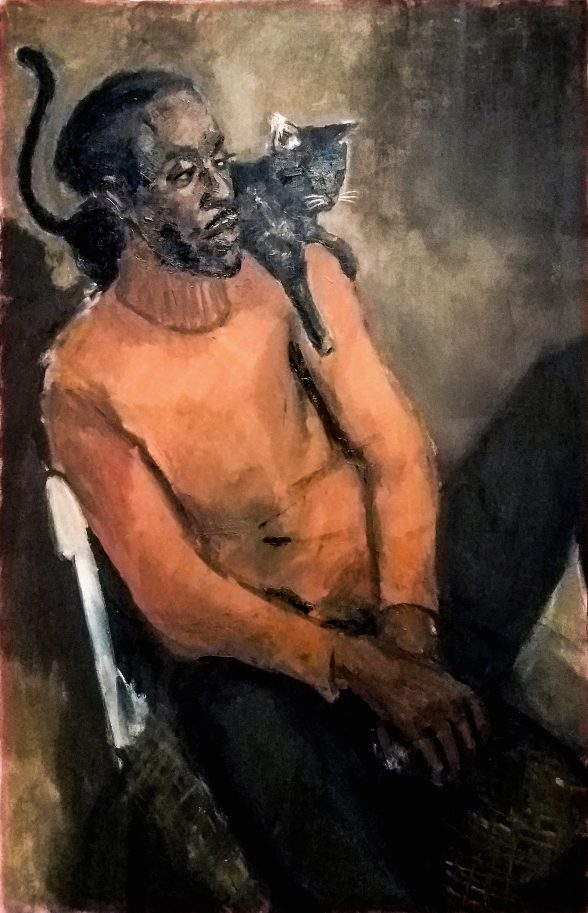

Unlike the more chaotic, experimental exhibitions on display at the New Museum right now, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Under-Song For A Cipher is meditative and calm. Placed around the perimeter of one long gallery, the 17 new figurative paintings by the Turner Prize finalist British artist are all larger than life and depict what feels like an extensive cast of characters in intimate moments. Some lounge, some dance or pose with animals, all looking soft and thoughtful. Lushly painted with a muted palette of deep browns, greens, blues, and grays that contrast beautifully against the heavy red-orange color painted on the gallery walls, the ambiance is dreamy and serene, like entering a shrine for the mysterious mythic figures on the walls.

The oil paintings all have rather poetic titles ( “Ever the Women Watchful,” “In Lieu of Keen Virtue”) that only add to intrigue of the story behind the individuals portrayed. While you might think these are portraits of real people, the mysterious population of men and women was created from the artist’s imagination.

As a writer and a painter, Yiadom-Boakye has a knack for creating tableaux that suggest a narrative and blend the historical, current, and imaginary. Aside from the style of clothing, there is very little to distinguish the settings – and that’s intentional. These people could just as easily exist in the ‘90’s, or even the ‘60s, as in 2017.

Moving Beyond Inspiration

Yiadom-Boakye’s work hints at historic European oil painting, certainly Manet, perhaps Rembrandt. Softly painted and dark, but luminous, her figures seem to glow from within. However, conspicuously, in contrast to the almost exclusively white subject matter of the old European masters, Yiadom-Boakye diversifies representation in traditional art media by painting exclusively black figures. She has explained that she paints black subjects simply because she is black and these are the people that populate her imagination; but the impact is not quite so simple. Given the lack of representation of people of color in both the historic and contemporary art scene — especially in museums — her decision to paint black people is inherently political. Yiadom-Boakye creates a space celebrating people of color in a setting where they have been historically excluded, i.e., the overwhelmingly white Western art world, and yet the scenes on display are decidedly normal. Again echoing Manet, the paintings are mostly scenes of people engaging in arts and leisure activities. A black man reclines in a field of grass, another drinks a cup of coffee, yet another poses with a cat on his shoulder. Joining the ranks of Kehinde Wiley, Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker, Barkley Hendricks, Hank Willis Thomas and other activist artists of color, Yiadom-Boakye’s representations point a finger at the white-dominated art world and show another way.

While her brushy figuration might make you think she’s a throwback to earlier times, Yiadom-Boakye’s painterliness is contemporary. The arrangement of her brushstrokes, loose and abstracted in certain areas, tight and meticulous in others merges the best of realism and painterly freedom. The mix of tight and loose brings to mind one of my personal favorite paintings, Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “The Banjo Lesson” (1893).

This is a painter who relishes her process. Though Yiadom-Boakye is well known for finishing her paintings in only a day, there is an impressive amount of layer and detail. And a viewer, too, should pay attention to how the works are built up and painted over, letting the underlayers show through in tantalizing tidbits here and there. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings provide just enough detail, never too much. I particularly enjoy the bright remnants of underpainting that peek through the heavy, muted tones. A tiny strip of bright red, green, or yellow goes far to contrast the mostly neutral palette, and gives a nod to the painting process. In the way the subject matter itself is said to be an accumulation of Yiadom-Boakye’s interests, research, and experiences pulled from all over, so too, the vestiges of the accumulated underpainting and past layers of bright colors, which were not hidden, become a part of the story; her complex process of painting mirrors the changeable, fast, and complex process of life.

Lynette Yiadom-Boake: Under-Song for a Cipher is on display at the New Museum (235 Bowery, New York, NY) until September 3rd.