Part 2 of my interview with Marianne Bernstein recaps her public projects in Philadelphia, which brought artists and the public together in the Dilworth Park underground, Love Park, and a vacant lot on South Broad Street. Read Part 1 of the interview. Artblog has been following the artist/curator for years. Here’s Libby’s interview with her from 2009 and here is Chip Schwartz’s review of Due North from 2014. And here’s a review of Bernstein’s Underground video project from 2009.

Roberta – You are now moving to Chicago after living in Philadelphia for 17 years. You’ve done many projects in Philly, some in public spaces. How does public curating differ from curating in a venue like the Icebox or Delaware Contemporary?

Marianne – I have been creating, facilitating, and curating in the public realm since my days living in New Haven (from 1990-2000). No matter whether it is a public intervention or an international adventure, it’s always very interdisciplinary (theatre, film, visual art, poetry, music, etc) and each project feeds the next. It’s also a personal quest. I am continually trying to challenge myself and others to open up- and then we move through our fears together to a new place of understanding. And there is always a party at the end.

- The Welcome House (2009)

In 2009 in Love Park, Philadelphia, we erected a 10’x10’ transparent cube (designed by architect Daryn Edwards) where each day a different artist created works inside the cube about the Park (which had lost its soul after they kicked out the skateboarders), and at night it became a four sided video screen featuring what had happened the day prior. This brought many different people into what they had deemed as a dangerous space. Eugenie Perret of Minima invited an Italian designer to donate gorgeous lounge chairs around the cube, and the Park completely transformed during and after those ten days. We worked with the homeless population, they became part of the piece and were featured working and dancing inside the cube with us in the films, as well as being invited to opening night Design Philadelphia, on the guest list. Many went back to the shelters, and got dressed up for the party. It was an extraordinary evening that broke down barriers, and changed the Park completely. It was soon after completely redone. - Shelter (2009)

Was a project/exhibition of a bi-level installation at the Painted Bride Art Center in Philadelphia. For six months, fourteen artists were paired with ten Philadelphia families facing eviction to make art dealing with issues of family crisis and homelessness. One of the artists Ricardo Rivera of Klip created a 3D video installation of an older, beloved woman named Gloria Brown ensconced in her living room on a large hospital bed taking calls on her red phone and talking with her longtime partner Albert Harrison. Gloria passed away the week before Shelter opened, and her daughter gave us her hospital bed which we projected the video on, like virtual reality. Her friends and lover came daily to sit on her bed in the gallery and pay tribute to her. Zoe Strauss, another participating artist also befriended and photographed Albert after Gloria died, creating some of her most memorable photographs in her retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Each artist worked respectfully for months with their family, creating work together for the final exhibition. - The Philadelphia Underground (2010)

In 2010, I curated a site specific video installation in which eight artists were challenged to create work exploring our neglected subway system and underused public spaces in Philadelphia. The videos were projected onto aging walls for three days beneath Dilworth Plaza: a (then) derelict underground public transit space, in the heart of downtown, adjacent to City Hall. The project also restored a statue that was the centerpiece for the space, engaged the homeless residents of the space to help clean the plaza, as well as provided live music, popcorn, and a red carpet as a makeover for the space as it was reinvented through the videos. Soon after, the site was given a radical makeover. - The Play House, Not a Vacant Lot (2011)

We created a new multi-purpose aluminum 8×8′ cube, a nomadic version of the Welcome House. Ten artist teams were invited to activate vacant lots throughout Philadelphia and create a short film about it. At night, these films were projected onto the exterior of the cube, which was installed as a temporary video installation and performance venue in a vacant lot on Broad Street. There are 40,000 vacant lots in Philadelphia. The intent was to demonstrate the potential for re-imagining empty space in new ways through artist interventions and neighborhood collaborations. The site has undergone a radical transformation since then and ignited a citywide discussion about the future of empty lots. - The Play House: Beyond What Was (2012)

In 2012, the second installation of the Play House cube traveled outside of Philadelphia with support from an NEA grant. As a nomadic architectural structure, it was transported to New Haven to activate Artspace’s The Lot, an outdoor art and performance space (which I founded in 1998) while exploring the social and human implications of homelessness and addiction. Artists were invited to make work on site within the cube to call attention to this problematic space and the complex social issues within New Haven. We spent weeks getting to know men and women who suffer from addiction who in turn worked with us to create large self-portraits and stories featured on the 8’x8’ cube.

There are of course differences between public curating and curating for a gallery. However the process for me is very similar. I start with a vision or a new idea, and then work backwards. It is a very organic, improvisatory, flexible process that develops as it goes. Curating in the public sphere is more difficult because you have a lot more variables and challenges, such as working with non-artists to get things done, weather, permit, and time issues. But these challenges also make it very gratifying in the end and often lead to new relationships and memorable serendipity.

R – Will you carry on your work in Chicago?

M – For sure. There are many wonderful artists working in Chicago like Theaster Gates, Jefferson Pinder, Candida Alvarez, and others that I can’t wait to hang out with. I’m sure it will take some time to get acclimated, but I look forward to making new friends and diving into this new adventure.

R – You are an independent curator and an artist. Talk about the way you work.

M – These projects eventually tend to gather lots of friends and supporters along the way, and we rely on the kindness of strangers and most of all, the generosity of the participating artists themselves.

R – How does your own art making influence your curatorial choices?

M – A consistent theme in my work and my curatorial choices is the foreign. For Tatted, (a monograph designed and produced by Brian Jacobson) of South Street’s Philadelphia tattoo culture (photographed on three city blocks from 2006-2009), I was endlessly curious about tattoos -which at the time- seemed very foreign to me. I was especially interested in the back story of each person’s tattoo choices and I accompanied each portrait with their handwritten note. Most of my adult life I have pursued the foreign, in order to better understand others and myself: photographing random strangers on the street, creating self portrait dreamscapes in the studio, searching to capture the mystery of everyday objects and places, and in more abstract works using braille and foreign words. In New Haven (2000), I curated an exhibition at Artspace titled Foreign Bodies: art, medicine, technology. This show was, perhaps the beginning of my interest in the foreign, in this case the inside of our bodies.

The homeless, the well heeled, the marginalized, rich poor black white gay straight the good the bad and the ugly –I am interested in humanity. This drives all of my work. My photographs, films, and projects are merely a vehicle to explore what’s foreign in both ourselves and others to allow for greater acceptance, less fear, and a kinder world.

R – How does the independence you have as a curator influence what you do? If you were attached to a museum would your job be different? How?

M – I don’t think I could curate the way I do if I was attached to a museum.

I tried 9-5 in my 20’s and it didn’t agree with me at all. I spend an inordinate amount of time alone, reading thinking walking swimming and do a lot of work in my head. It’s very zen. I love my friends, but I need my solitude in between projects to vision and navigate my ideas and actions clearly.

R – What’s your background? You are entrepreneurial. Did you go to business school or have a mentor along the way or are you just innately a can-do projects person?

M – You are the second person to call me entrepreneurial. I remember my reaction the first time someone told me this earlier this year. I was actually slightly offended, still clinging to the idea of artist as solitary genius. However, the idea of the modern artist as creative entrepreneur is gaining traction and there’s some truth to it. Our society is changing the way art is made and who is funding art. I think what entrepreneurs have in common is a love of innovation, tolerance for risk taking, an ability to jump on opportunities as they present themselves, and exploring new possibilities within closed systems. I learned a few things watching my 96 year old father navigate business and the arts. Perhaps he is my mentor. I do love projects though. Making, exhibiting, and selling my photographs was never enough for me. I never wanted my art to be about me. The process of creating work and creating transformation of some sort is what excites me, the final product is merely a record.

R – Many of the works in the show have stayed in my memory for their beauty or resonance. The one that sticks most is Loredana Longo’s The Line, a documentary photo slide show of a performance the artist worked on with seven immigrant girls from North Africa and some neon lights. Talk a little about the role of the refugee crisis in the show.

M – We’re living in an age of anxiety, without institutions and sources of meaning to trust. The final gallery is meant to evoke not just the refugee crisis, but also beauty and terror, death is all around. But as our eyes adjust to the darkness, we see more and more and the room brightens. The young African girls in Loredana’s photograph offer up an important antidote to hatred: that the world is too complicated to fit into a narrow political belief system. By engaging directly with the girls to creatively illustrate their harrowing journey, Longo helps us see these foreigners up close in a new way—we are surprised at their resilience under great odds. I wanted to instill in the the viewer a sense that there are no easy answers that can explain our existential problems. Progress is not made by crushing foreigners; it’s made by recognizing their humanity and finding balance between competing truths.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

—T.S. Eliot

The Backstory of the Projects

M – And then there is the dark underbelly to my projects, that I often don’t discuss because nobody asks; the backstory, the difficulties and insecurities, the obstacles, my own personal doubts as an independent renegade, taking a risk. Lately, I have been trying to dig deeper to understand better and communicate more clearly why I do what I do. Maybe it’s all about creating a mirror, imagining challenging circumstances where I can create a reflective surface in an attempt to better understand myself, my world, and the people around me. The mirror reflects the best and worst of human nature. In Sicily, there is the Sirocco wind, a hot dusty wind from North Africa that makes people do crazy things. We were there last year during one of them, a dark day, where the Mafia wreaked revenge on the Director of the Parks near the Madonie, by dousing rags with gasoline, placing them around the necks of stray cats and lighting them on fire as they ran into the forest. We saw the flames from the road, everything seemed on fire that day, hell had a glorious day.

Past projects, and especially Due North and Due South became for me, laboratories for observing communication and its breakdown. Within our artist group, which functioned as a family, a theatrical troupe of sorts getting to know each other over the course of three years- there were good times and difficult times— breakdowns, pettiness, jealousy. As a curator and facilitator, my learning curve was steep, trying to navigate being a leader and not controlling. While working with partnering institutions I had to learn the art of diplomacy (still working on this); as an artist, I had to grow as well.

The challenging often difficult process of trying to understand myself and others is integral to everything I do, in my marriage, my personal life with friends, as a mother, and as a teacher, curator, artist. It’s all the same to me. The artists I choose are invited to self-reflect as well, some are further along than others, but I do believe the emotional learning curve is great for everyone these projects touch and is the source of its energy. In the end, it’s not what the work is about (doesn’t need to reflect social or political issues), it’s that we as artists took a risk, went through something profound and translated that energy into making authentic work.

Truth has value.

Face to face communication is in short supply these days. Our country is polarized, the world is a mess. Pursuing a passion or an idea without giving up when others try to shut you down or don’t understand, causes many young artists to give up. The best advice I ever received was by a charismatic architect/artist/dreamer from New Haven, Tom Luckey who developed the amazing Luckey Climbers in children’s museums around the world. He had faith in my projects from the beginning because he saw a kindred dreamer, and said to me: Don’t stop. Keep going. Don’t stop. Tom had a horrible accident soon after that, became paraplegic, and passed away. I often hear his words in my head, and they guide me to this day.

Mixing established and emerging artists in Due North and Due South

Fata Morgana/Mondo Nuovo Peepshow: sculpted cast porcelain, wood, plexiglass

Courtesy of the artist and Cade Tompkins Project

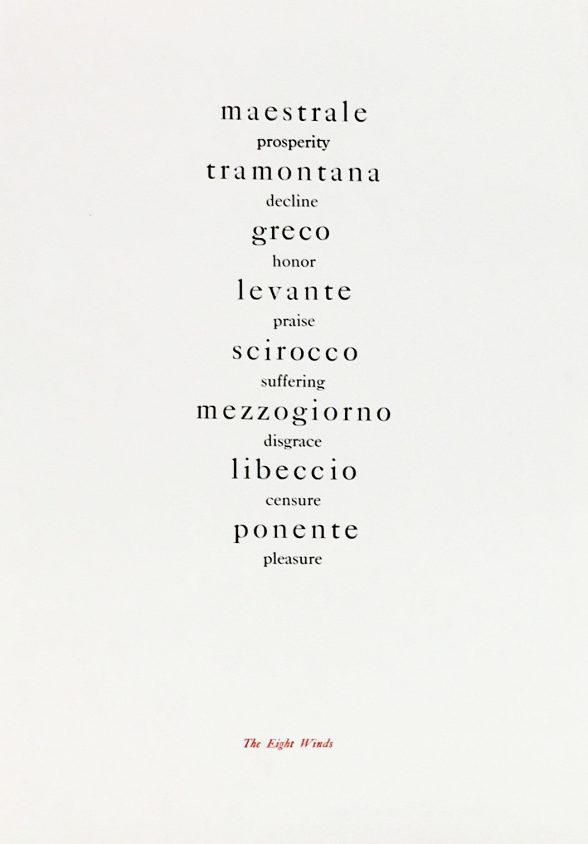

The Eight Winds

Letterpress, printed by CR Ettinger Studio

The Line

Single chanell HD video on monitor

Courtesy of Francesco Pantaleone Gallery

Shown at Due South

I generally like to mix emerging and established artists, with a few stars. Akin to cooking a delicious soup, a little of this a little of that, topped off with a little extra something something.

For Due North and Due South, my main quest was to find out who the best contemporary artists were on those islands and to meet them all personally. This was pretty easy because most of them know each other.

For Due North in Iceland, I met most of them pretty quickly but not all of them because some had left and already were becoming stars in their own right, like Ragnar Kjartansson and Shoplifter. As it turned out, Magnus Sigardsson invited me to join their group for dinner in 2014, when they were part of a nomadic international show living in campers in the courtyard at MOMA PS1. It was a truly memorable night, very hot and they were drinking and playing guitar and having a blast together trying to figure out what they were going to do there. (They ended up performing in a sea of bath bubbles). Shoplifter was there and very kind to me, kind of taking me under her motherly wing. Then Kjartansson showed up. That man took my breath away, he is now perhaps one of the most famous beloved artists on the planet. Serendipity (and island magic) created the final lineup for Due North, and Kjartansson agreed to participate.

For Due South, the Italians were a mix of South and North. Like Iceland, many of the contemporary artists who were originally from Sicily had begun traveling to the North and to Europe. Contemporary art is just beginning to blossom in Sicily, and initially it was difficult to find these artists. Interestingly enough each of the curators I spoke to mentioned different artists as their favorites. (struck me as a sort of tribal loyalty). The Kjartansson/rock star parallel for Due South was definitely the British born artist Isaac Julien, whose mother was born in the West Indies. Julien’s name came up when we were visiting Palazzi Gangi, one of the many palazzos where Jane Irish painted. The Princess, Carine Vanni Mantegna mentioned to us that Julien had also fillmed there, in the sumptuous ballroom made famous in the 1963 film The Leopard, so once I was home I investigated Julien’s work.

He created a multi- channel video installation titled Western Union: Small Boats (The Leopard) which I wanted to show for Due South, but it was too expensive. In the end, Tom Heyman, the Director of Metro Pictures was kind of enough to help us locate the two light boxes created alongside the video.

The light boxes work perfectly in the third gallery, especially in conversation with Matthew Mazzotta and Sujin Lim’s video work about the beach at Pozzallo where the migrants drowned. That beach, in real life is directly across from the boat graveyard, as it is in the gallery. They also create a wonderful conversation with Kelsey’s lightboxes also in the same room, about the past and present cultures merging and colliding- and with Flavio Favelli’s Damnatio Memoriae (condemnation of memory) in the adjacent room. We want to forget history– that these migrants, who are drowning, once lived and ruled in Sicily.

On hanging the show:

As with Due North, I was interested in transformation, both in the process and the exhibition. The idea is to transport the viewer to Sicily through sight and sound, and through description with Zya’s audio piece: smell, to provide a visceral experience.The exhibition, like the project took on a shape of its own, with its own layers.

Works are divided into three rooms. Bieberham: introduction/overview to themes of the show, Sicily as place and melting pot of major civilizations (Wattles), unfinished ruins (Cristaldi), geologic/farming aspects (etna- Nonino, Heron and Tyson, Cristaldi, Baronello, Levy; personal journeys (Perrone).

Dupont 2- City, getting a sense of the chaos, liveliness/ strange beauty (Canalis and Modica)sense of history, comedy/tragedy (Ettinger, Favelli, Kessler, Battaglia), exclusion (LaRocca) Dupont 1- Refugees (Longo, Julien, Mazzotta and Lim, Bernstein).

In light of recent geopolitical and social upheavals, international dialogue is more pressing than ever before. By examining a place from both inside and out, the artists created both intimate personal reflections and works suggesting that we all are foreigners somewhere. The recent refugee crisis has made many fearful of the mobility of foreign bodies, ideas, and cultures. Conversely, Due South seeks to explore the back and forth of both space and conversation: bringing artists across borders, and importing international artistic perspectives back home.

We must try to understand and take care of each other– It doesn’t matter how and where; the refugee, the foreigner could one day be you or me.