A riot is the language of the unheard…

—Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

The theme of this year’s sixth annual BlackStar Film Festival, a celebration of independent black cinema curated by artistic director Maori Karmael Holmes, was Resistance. The festival, which ran from August 3rd through 6th in various venues in Philadelphia, featured over 60 films, which focused upon political and social uprisings around the world and in the United States, from the upheaval of the 1960s to the Los Angeles riots of the 1990s to the present.

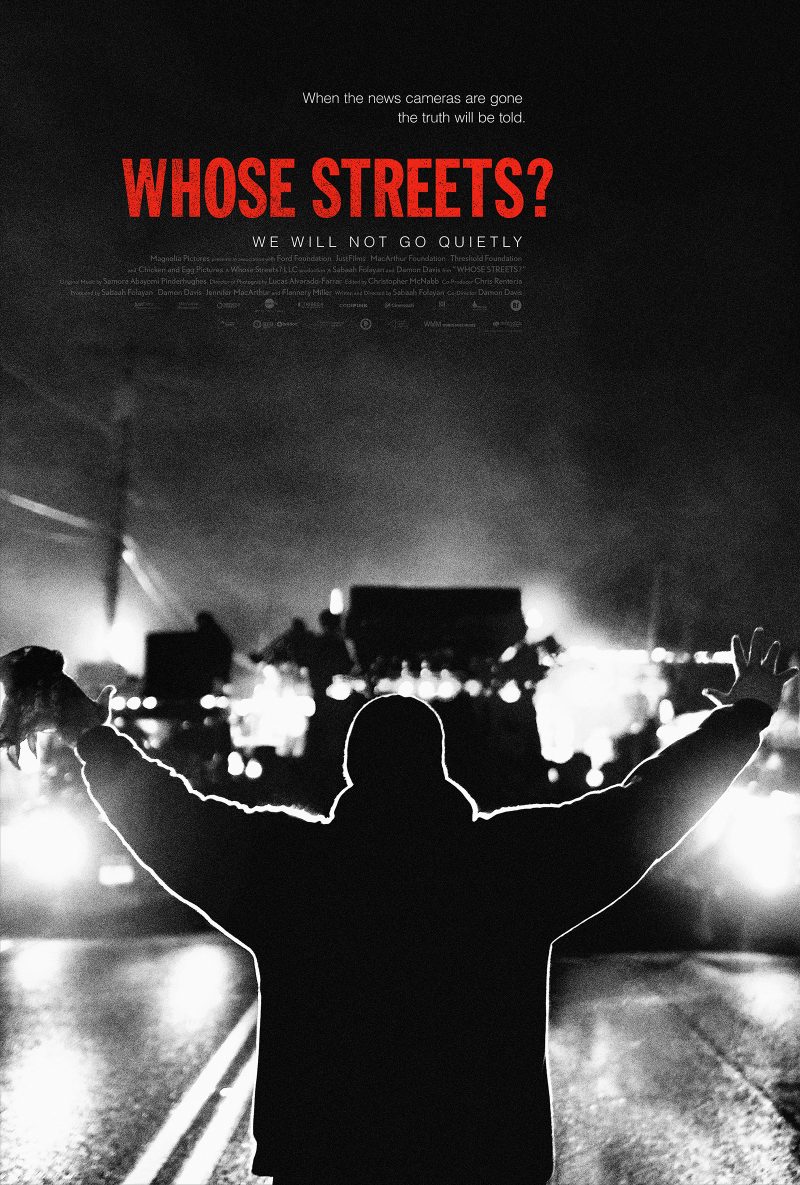

One of the films featured at the festival, “Whose Streets?”, is a disturbing 90-minute documentary, directed by Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis, about the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, which occurred in August 2014 and afterward, in the aftermath of the shooting of an unarmed, 18-year old African American, Michael Brown Jr., by a white Ferguson police officer.

A film from the point of view of the community

The Michael Brown incident, together with other similar infamous incidents which have occurred over the last years, have focused the world’s attention upon the plight of African Americans in our country, particularly at the hands of our police forces. “Whose Streets?,” however, is less about the shooting down of Michael Brown than it is about the community that reacted to his death in waves of grief, vigil, and protest.

The film is designed as an immersion in the community’s point of view without regard to, and even with disdain for, the already well-documented points of view of the authorities, the government (including then President Obama), and the mainstream media. While some may criticize this as biased, this point of view gives expression to the unheard voices of the community, to the overlooked side of the story.

“Whose Streets?” is a patchwork of footage of the uprising in Ferguson, some of it from the national media, some home spun, as well as interviews with activists and leaders in the community, and glimpses into the daily lives of a number of families living there, interspersed with bits of text – local tweets (“I just saw someone die OMFG”), rap (by Tef Poe), and clips of poems — which illuminate the struggles being portrayed.

The military response of the authorities

There are many vivid, unforgettable, and moving portions of the film. First, the frightening military response of the authorities to the protests, which began as non-violent assemblies and candlelight vigils, but later included incidents of violence against property, arson and looting. While some conservative media outlets have misleadingly characterized the demonstrators as violent and high on drugs and alcohol, what stands out in the film is the simmering, threatening violence of the police and National Guard Guard, who appear in full riot gear, wearing gas masks, with their armored vehicles and automatic weapons and tear gas and rubber bullets and attack dogs. And these troops turn Ferguson into a war zone and react ruthlessly to crowds of protesters, the overwhelming majority of whom are peaceful. Indeed, the protesters undertake to keep their hands in the air, and beseech the police and National Guard not to shoot them. “Please do not shoot me dead, I’ve got my hands on my head,” they cry, they beg, they taunt, a plea some have attributed to Michael Brown before he was shot down.

The community’s endemic fear of the authorities

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the film is its portrayal of the community’s endemic fear of government authorities, fear that has existed for decades before the Michael Brown incident and which encapsulates the African American community’s feeling of being under attack from and in danger from the police. This entrenched fear gives Ferguson the atmosphere of an unsafe place for its inhabitants, who believe their safety has been undermined by, rather than fostered, by the police.

The community’s fear is embodied in the film in many testimonies by Ferguson residents. In a scene that breaks your heart, a little girl expresses fears that something will happen to her mother, one of the leaders of the protests, and that her mother will never return home. On a less serious note, the movie displays a resident’s dark humor about the situation in a quick cut to a doormat of a house emblazoned with the words: “Come back with a warrant.”

As the film recounts, the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department ultimately found a long-standing history of abuse in which the government of Ferguson used its police force to stop and intimidate its residents, and to use petty infractions as a cash cow for the city government. The grievances of the protesters appear to have been as much a reaction to that abuse as to the senseless death of Michael Brown. The people declared that they were not fighting for their civil rights, but for the right to live, in their homes, in their streets.

The imprint of racism

Of course, the heart of “Whose Streets?” concerns racism – played out in an African American community with a nearly all white police force. One remarkable segment of the film highlights the arrest report of one of the activists, in which the arresting officer describes the “tribal chanting” of the crowd. Here is one of those “tribal” chants: “It is our duty to fight for our freedom, it is our duty to win. We must love and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

One of the most controversial aspects of the Michael Brown story is a video which the government released purporting to show that prior to his encounter with the police, he had allegedly robbed a convenience store. The film does not address this issue in any detail, but many commentators have pointed out that this action by the government was a disgraceful way of suggesting, misleadingly, that Michael Brown was a criminal, and that shooting him down was somehow justified.

The film includes a clip from a television interview by George Stephanopolous of Darren Wilson, the unindicted police officer who shot Michael Brown, in which Wilson describes the look of Michael Brown as “demonic” and insists that “You can’t perform the duties of a police officer and have racism in you.”

I was thinking about the names – Brown and Wilson – as I watched that interview. About black and white. About the divides between the black and white communities in our country. While those divides may be changing as the non-white population of the country grows, “Whose Streets?” presents a profound demonstration of the ongoing intolerable, pernicious effects of racism and racial injustice upon our society. When Officer Wilson made that comment denying racism, the nearly all black audience at the BlackStar film screening I attended erupted in jeers. I wish there had been a larger white contingent there to witness that.

The question of hope

The uprising in Ferguson, together with various other atrocities in the country, ushered in the Black Lives Matter movement. Whether the BLM movement foretells hope for racial justice remains to be seen, although the election of 2016, and recent disturbing displays of white supremacy in Virginia (and the president’s disgraceful response) suggest that the road ahead is fraught with violence and with white institutions of government that are no more enlightened now than they were during Martin Luther King’s time.

“Whose Streets?” suggests that hope for racial justice lies in part in the hands of the children of Ferguson, children who have grown to understand the value of community, of unity, of rising up to challenge injustice. The other message embedded in the film is that those of us who care cannot sit on the sidelines — that we must join hands with those children.

Michael Brown’s body was left lying in the street for hours after he was shot by Officer Williams. “Whose Streets?” describes efforts to create a teddy-bear memorial on that spot, which were repelled by the authorities. I wondered about the significance of the teddy bears and learned that it may relate to the hope embodied in the remarkable poem by Langston Hughes, “Kids Who Die,” written in 1938 about Southern lynchings, and eerily resonant today. Please take a moment and listen to Danny Glover’s recitation of the poem.

“Whose Streets?” is playing right now at Ritz at the Bourse. See it if you can.