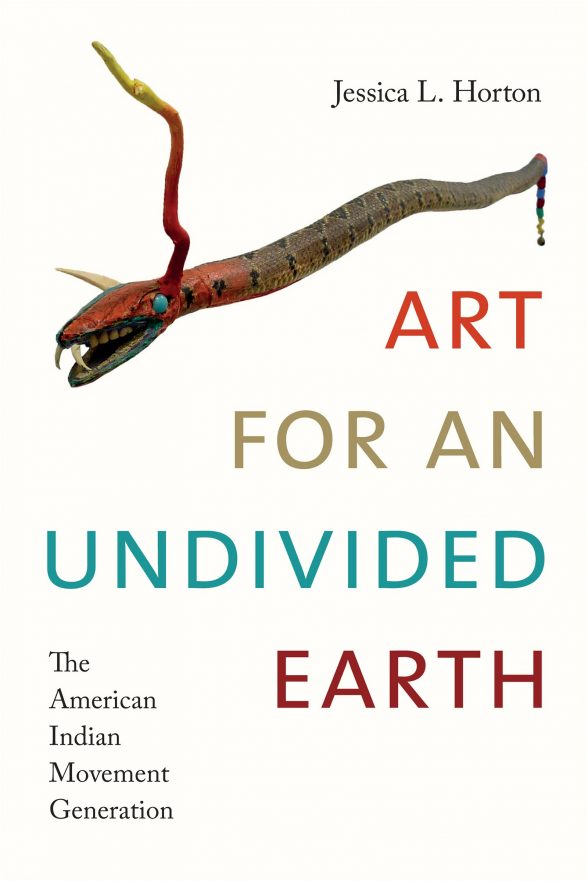

Art for an Undivided Earth; The American Indian Movement Generation by Jessica L. Horton

Jessica L. Horton Art for an Undivided Earth; The American Indian Movement Generation (Duke University Press, Durham and London: 2017) ISBN 978-0-8223-6981-3

Jessica Horton’s study is scholarship as advocacy and a significant contribution to the ongoing discussion about how to develop a truly global perspective in the study of contemporary art. She analyzes the work of artists from the generation of the American Indian Movement – which worked towards civil rights for indigenous Americans and began roughly in 1968 – including Jimmie Durham [whose work will be shown in a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art this fall], James Luna, Kay Walkingstick, Robert Houle and others. Horton writes from a position of respect for their world view which, unlike that of Europe, is spatially, temporally and materially interconnected – a conception which she terms an “undivided earth.” This is a scholarly book with the usual apparatus and takes into account a range of theoretical approaches but is written clearly enough to offer something to serious general readers.

The book traces the contemporary artists’ affiliation with ancestors who preceded them in traveling internationally and investigates how they have negotiated their own cultural history using both archival and performative sources. It debunks commonly held beliefs that the Native Americans’ work primarily concerns issues of identity; that there is no precedent of Native Americans who attempted to deal with the divide between their culture and that of Europe; that no art by Native Americans was shown in early twentieth-century international exhibitions; and that Native American artists continue to be excluded from such venues.

Among the topics covered are the place of performative traditions in history, the legacy of nineteenth-century racial thinking on U.S. Law and in turn on definitions of art by Native Americans, the possibility of Native American agency with respect to European institutions, new materialism, primitivism, and institutional critique. Horton suggests that these artists’ works offers significant contributions to an evolving global conception of knowledge, to the possibilities of art, and to an understanding of the relationship between nature and culture, which the Western tradition has always treated oppositionally.

Others Book Recommendations from Duke University Press

This is only one of the un-requested books that continue to arrive from Duke University Press. Duke publishes important analytic work that falls outside the art publications associated with museum exhibitions and hence the art market. The flow of their books is only a problem because so many of them are compelling – often on subjects about which I had no prior interest – and they distract me from other reading.

Among those that await my attention are:

⁃ Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s second volume of collected essays “Photography After Photography; Gender, Genre, History;” Her first compilation, “Photography at the Dock; Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices”(1994) was essential to my understanding of what serious critical writing could be, and left much other writing on photography looking insignificant.

⁃ “We Wanted a Revolution; Black Radical Women 1965-85, A Sourcebook,” a book published in connection with an exhibition – at the Brooklyn Museum through September 10 – that is important as a reference source, which assembles a range of material, much of it previously hard to obtain, about a largely overlooked history at the intersection of art, feminism and race;

⁃ “One and Five; On Conceptual Art and Conceptualism” by Terry Smith, a series of essays whose author participated in the Conceptual art movement as artist, critic and art historian.

Inventing Downtown; Artist-Run Galleries in New York City 1952-1965 by Melissa Rachleff

Melissa Rachleff “Inventing Downtown; Artist-Run Galleries in New York City 1952-1965” (Grey Art Gallery, NYU and Del Monico Books Prestel, New York and Munich, London, New York: 2017) ISBN 978-3-7913-5558-0

This fascinating book is valuable as considerably more than a catalog to an exhibition held at the Grey Art Gallery this past winter which travels to the NYUAD Art Gallery at NYU Abu Dhabi this autumn (opening October 3, 2017). It is a significant contribution to the literature on the generation of artists in New York City following the first generation of Abstract Expressionists and focuses on the institutions they created in order to exhibit their work. The author describes it as a chronicle – a compilation of information gleaned from extensive interviews with surviving artists and others involved with the art world, as well as archival sources. She does not attempt an historical analysis but includes the messiness and asides of actual events rather than the smoothed-out linear narrative of art history. Part of its value is to remind us of how much of canonical history depends upon the choice of focus, and what is inevitably excluded. The book is a treasure trove of period photographs of the artworks as installed, many of the participants, and a visual record of work by many forgotten artists, including a number of women.

Commercial activity involving contemporary art was in its infancy in the 1950s, and Rachleff charts the leading role of artists themselves in presenting their work and creating public discussion around it – something better-documented for artists in New York in the 60s rather than their predecessors. Much centered around several cooperative, artist-run galleries including Tanager, Brata, and Hansa, which have already entered the history of the period. They were involved in ongoing tensions between figurative and abstract art and have been extensively recorded by someone intimately involved at the time, the art historian Irving Sandler.

Another group, including the City Gallery, Reuben Gallery, Judson Gallery and Delancy Street Museum rejected both the cooperative nature of those galleries as well as gallery conventions and were significant venues for new forms which crossed disciplinary boundaries; these included happenings, performance art and installations. Artists also presented their work in private venues, including Yoko Ono’s Chambers Street loft and at Park Place, a building where where artists developed living/working spaces and created a common area for showing work. There were several groups which responded to contemporary politics including the NO!art Group, Phyllis Yampolsky’s Hall of Issues at Judson Church, The Center – which organized outdoor exhibitions and festivals in the Lower East Side, and Spiral, a collective of African American artists. Finally Rachleff includes Greene Gallery, which was not artist-run or downtown, but it exhibited many artists from that community. Her account ties in nicely with Judith Stein’s highly-readable and much-lauded recent book about Greene Gallery’s founder and director, “Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Modern Art.”