Functional art, and architecture by a self-taught architect

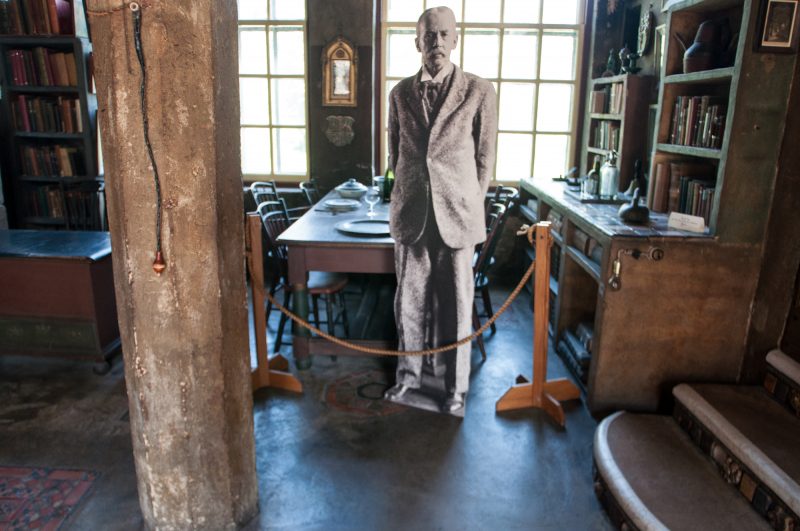

Inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement of 1880-1920, Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930), created a marvel of functional art in his hometown, Doylestown, PA — the Gothic Castle, Fonthill. Located outside the magnetic pull of the big city nearby, Fonthill may not be on your radar. But, spend an hour in the building with the knowledgeable guide who takes you around, and Mercer, a driven and enigmatic individual, self-taught architect, and early DIY’er, pops to life; and his castle-home, in all its idiosyncratic glory, will leave you pondering its creation, achieved through use of an ancient Greek architectural technique that involved buckets of wet cement ferried upward into the structure in a rope-and-pulley system aided by the muscle power of Lucy the horse. It’s true.

While Fonthill, constructed between 1908-1912, does not resemble them in the least, its majestic weirdness and manic energy allies itself with the obsessed wall ensembles of Albert Barnes (1872-1951), the monumental sculptures, Watts Towers, of Simon Rodia (1879–1965), and the swoon-worthy neo-Gothic cathedrals of Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926).

Who was Henry Chapman Mercer?

A polymath history buff, who was also an explorer, collector, self-taught architect, trained lawyer, businessman and maker of ceramic tiles, Henry Chapman Mercer (HCM) was an old fashioned man who spent a lot of time traveling in Europe and loved castles. Apart from his pioneering use of cast concrete as a building material (fueled in part by the fear of fire that could burn the place down), his taste skewed historical. His castle, which was his home from 1912 until his death in 1930, evokes the Gothic era; he collected Colonial-era artifacts; and led archaeological expeditions to Mexico. He hated the writing of Ernest Hemingway and his newfangled, no-frills prose.

Born in 1856 in Doylestown, HCM grew up in comfort but not in great wealth in a family, whose lineage included soldiers, lawyers and statesmen. His mother, Mary Rebecca, taught Sunday school and painted for pleasure. His father, William, was a commissioned Naval officer who loved history and horticulture. Mercer graduated from Harvard (1879) and from the University of Pennsylvania Law and was admitted to the Philadelphia Bar (1881), but never practiced law.

His passion was history and anthropology and after graduating he traveled in Europe and Egypt and spent much time in Germany, where his sister, Lela, was married to a German military man and lived in Bavaria. Later on, Mercer collected ancient archaeological artifacts and tools of a more recent era, the American Colonial. The kitchen tools, farming implements and other objects were not generally deemed worthy collectibles at the time but to Mercer they were valuable links to the past. His fieldwork was serious and he was appointed a curator at the Penn Museum and contributed articles to scholarly journals and gave a talk at the Franklin Institute in 1897.

Later, his interest in tools and in making things in an historical, non-industrial way turned him to pottery. He studied in Bucks County and in England, where he met acolytes of William Morris, the Arts and Crafts Movement leader. Ultimately, Mercer created the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works as a business for decorative tile for home and commercial use (The word “Moravian” was added to the business’s name as a nod to the story tiles that came out of the Moravian Church, some of which Mercer adapted for his use.) And of course, the Tile Works was created out of cast concrete, same as Fonthill.

Mercer was a social person and did a lot of entertaining, including opening the castle as a showplace to potential clients to see the tile in situ and imagine it in their spaces. But he never married and when he died, he gave the Moravian Tile Works to his business associate, Frank Swain, who he allowed to live in Fonthill with his wife until they died.

Some considered the man a puzzle, a bachelor, an eccentric who built a castle in Doylestown. During World War 1, his many ties to Germany — friends, family — caused him to be critical of U. S. foreign policy, a stand most likely not popular with his neighbors. Mercer died in 1930, at age 74, of Brights disease and myocarditis. Active in the Bucks County Historical Society, he had already gifted the Mercer Museum (made of concrete and housing Mercer’s Colonial-era tool collection) to BCHS in 1916. His will created a trust for Fonthill to become a museum. Fonthill is now administered by BCHS, by agreement with Fonthill’s Board.

The Tour

The story of HCM and Fonthill, told splendidly by our tour leader, Mary Helen Hughes, unfolded as we walked the halls, climbed the stairs, entered the private and public rooms of the castle. To say you need a tour guide is an understatement, and in fact, you can’t free-roam around the inside of the castle. The interior is only available by guided tour.

Like all oddities that were created long before our time, Fonthill’s mystery needs life breathed into it by a storyteller. Our storyteller was amazing in her command of the history and in her generosity to share it. The day we visited was warm; there is no air conditioning in Fonthill; the many windows are closed; and we had many rooms to see and lots of stairs to climb (the tour — of 14 of the 44 rooms — takes about an hour). But our busy tour guide stopped and generously answered our questions. On the way out we got a bombshell story about Mercer, the dog-loving bachelor, who was previously characterized as solitary but social and not a recluse. Before exiting and saying our good-byes, our guide asked us where we were from. Chuck and Iris responded “Baltimore.” And our guide said Mercer had a love interest in Baltimore. Oh, we said. She went on to say that as a young man, Mercer had contracted a venereal disease, and his doctors advised against marrying and having children, so the man lived alone in his big castle.

This sad bit of biography is still washing over me. Henry Chapman Mercer loved dogs (family substitute?); he had a bounty of creative energy, which he put to good use in his artifact explorations and, especially, in creating beautiful tiles and amazing architectural fantasies. Who knows whether with children and a family he would have been as successfully creative. But for sure, without family obligations, he was uncommonly productive. And he left his oeuvre in the public trust, which makes us all his children, his heirs. Go enjoy your castle.

Fonthill, East Court St. and Route 313, Doylestown, PA 18901. Guided tours, Reservations advised

Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society, 84 S. Pine St., Doylestown PA 18901

The Moravian Pottery & Tile Works, 130 Swamp Rd (Route 313), Doylestown, PA 18901

Fonthill photo outtakes – Photos by Chuck Patch