Despite the explosion of net-only content, there are still many people who like the feel and look of print on paper, and I’m among them. The world of hard-copy periodicals can seem endless, and beyond the well-known and lesser-known titles there’s a world of small publications, some produced occasionally, others more-or less regularly, which aim to attract their own, niche audiences. The problem is finding them; many will never make it into library catalogs or indices, and their lifetimes are often short. I attribute much of my own, albeit slight, familiarity to P.S.1. which has the largest selection of art, design and visual culture periodicals I have found — in the entry area where tickets are sold — and the staff is happy to discuss the titles. I’ve picked a randomly-selected few, and hope to make this an occasional topic.

Each annual issue of “Clog,” a small-format journal, published in Brooklyn, with basic, black and white illustrations, concentrates on a single topic related to architecture. I picked up the 2014 issue titled “Guggenheim,” but previous topics have ranged from “Miami,” “Brutalism” and “Big” to “Prisons.” It is a very good read, with each author allotted no more than two double-page spreads of text, sometimes bolstered by images and charts. The editors seem to favor presentations that are graphically lively, which adds to the reading pleasure – although, betraying my age, I had some difficulty with the pages printed on colored backgrounds and with the small type. If they have to stick to that scale they might at least use a serif type.

The more than fifty contributors live on four continents and took a wide variety of approaches, and the editors must have insisted on the consistently clear prose and lack of insider jargon. Chapter titles give a good idea of the breadth of the subjects and attitudes: the editors’ “Guggenheim, a dynasty in transition,” Hanna Cohn’s “Anything but white,” Matthew Hall’s “Pop architecture for fast art; Guggenheim’s brand identity,” Jack Self’s “Who the hell needs another Guggenheim?” and interviews with the museum’s current and former director and artist Cai Guo-Cuang, among others. I’d recommend the publication to readers in the fields of architecture and design, and to anyone else who finds the particular topic of interest. (Ed Note: Avril 50, 3406 Sansom St. in West Philadelphia, carries Clog.)

“Science of the Secondary; an atlas of things not yet discovered” is published by Atelier Hoko in Singapore, self-described as “an independent research lab focusing on investigations towards material and immaterial conditions that make up our experience of the everyday.” There have been nine issues so far, printed in editions of 400-1000 copies, and some have been re-issued; topics have included “Socks,” “Habitat,” “Clock” and “Window.” New issues are announced with events, often interactive, that sound very much like art projects.

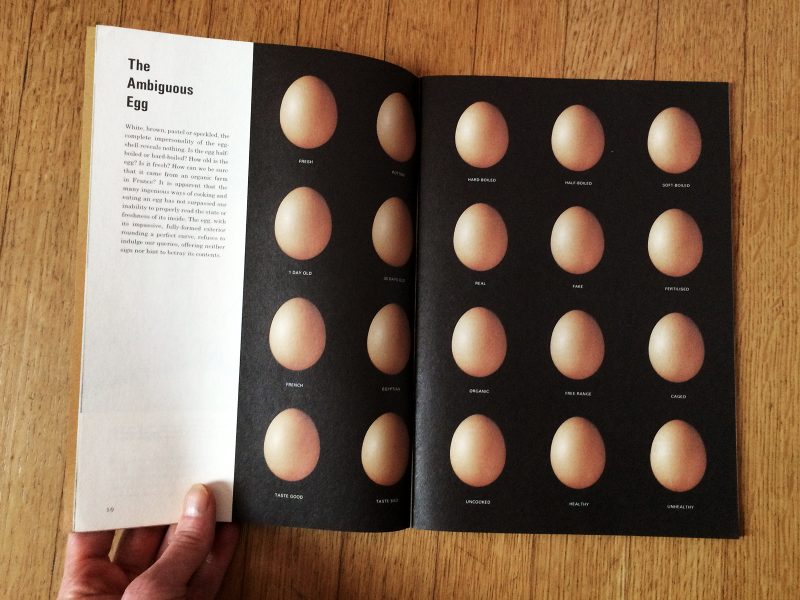

I am looking at issue No. 7, “The Egg”; It is printed on matte paper and is a comfortable size to hold in the hands. In 50 pages it addresses subjects from the inscrutability of eggs, that do not reveal their condition visually, and practical topics such as the ideal way to crack an egg and how to place one on a surface so that it will not roll off, to appreciations of the sensual experience of choosing eggs individually rather than buying them in a carton. This small publication encourages readers to slow down, to pay attention. It is more poetry than prose, and is unlikely to be appreciated by someone whose knowledge comes entirely from a computer screen or anyone who needs crowds and loud music to have a good time.

“Art Handler” is a give-away printed in black and red on newsprint in tabloid format, and has neither colophon nor any other indication of who is behind it or where it can be found. For all I know, I am looking at the only issue – un-numbered and un-dated, which I picked up at PS1 sometime ago. There is a statement of intent, printed in a small box, stating “Art Handler is a new print and online publication with deals with the social and cultural impacts of behind-the-scenes labor in the art world. It allows critical discussions for both handlers and facilitators who depend upon them.” A Google search reveals that the publication exists online, and I have Issue 1, and 2 is online, but there is no indication whether its embodied form will ever recur.

I have always had great respect for those artists – and all art handlers are artists — generally-unseen or acknowledged, who so ably keep galleries and museums functioning with their skills. This publication gives them a voice and reveals the depth of thought which their day jobs inspire – not only about working conditions but about how the physical circulation and handling of artworks raises questions of the definitions and meanings of art. The issue includes Chuck Close reminiscing about his early experiences working for Richard Serra, and Robert Storr about his invisibility when handling art for McCrory Corporation, and a number of articles which discuss the possible meanings to be found in the physical circulation and handling of artworks, and how artists, including Ian Baxter, Walead Beshty, and Beatrice Balcou have used these as the basis of their work.

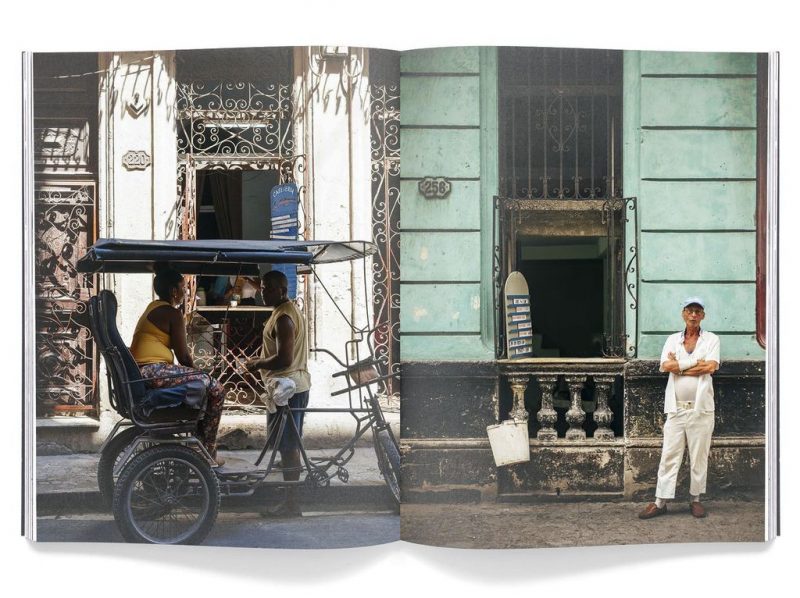

“Drift” is a lushly-illustrated, full color magazine, with each of its two annual issues devoted to a single city. Issue 3, which I picked up, addresses Havana. It took me a fair bit of looking through its pages to realize that the publication’s unifying theme is coffee. “Drift” is a coffee magazine which uses its focus as a vehicle for exploring the city, its history, social customs, economic life and the place of Cuba’s national drink in its previous and current economies. There are more pictures than text and the photographs have all the seduction of any travel magazine. The articles all have a personal point of view, and its hard to imagine anyone who reads “Drift” not considering a trip to Havana.

The articles are mostly short – introductions to a variety of people – on the island and those who visited Havana and brought away strong feelings about its coffee culture as well as foreigners living in Havana and doing business there. There’s a history of coffee culture in Cuba, a primer on the various ways the drink is served, an article about coffee roasters and and step-by-step directions on the proper way to use a Moka pot. I can’t imagine “Drift” continuing to find two cities a year where coffee is so integral to its sociality – but based upon this issue they have found a lens for viewing the world which should attract many followers.

(Ed. Note: Drift may be found at Barnes and Noble, 1805 Walnut St.)