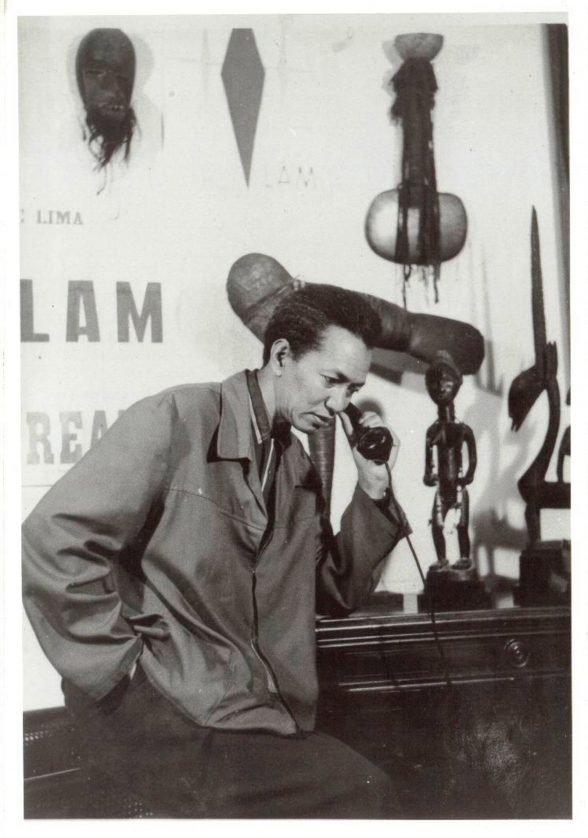

Wifredo Lam (1902–1982) is experiencing something of a moment – at least in Europe. The subject of a 2016-2017 blockbuster travelling show of over 200 works in Madrid, Paris, and London, the Cuban artist has not received the same level of attention here on the other side of the Atlantic, which makes the current show of 21 of his drawings at Lehigh University Art Galleries (LUAG) all the more significant. After over thirty years of frustrated attempts to bring these works from Cuba to the United States, gallery director and curator Ricardo Viera has finally succeeded in bringing these drawings from the private collection of the artist’s great nephew, Juan Castillo Vázquez. Make the pilgrimage to Bethlehem to experience this remarkable exhibition, which provides a unique glimpse into Lam’s imaginative world.

It’s easy to lose sight of Lam’s art amidst the drama of his life, but this thoughtful show puts the focus firmly on the work itself, even while acknowledging the importance of his early environment for his development as an artist. In his a presentation at LUAG on September 21, Juan Castillo Vázquez spoke about Lam’s childhood, the people and places that helped shape him as a young man before he departed for Europe. Born the same year that Cuba gained its independence, Wifredo Lam stands at a crossroads between worlds. Born to a Chinese father and a Cuban mother, Lam grew up immersed in his immigrant father’s Chinese traditions, the dominant Catholic faith, as well as Afro-Cuban religion (his godmother was a leader among local practitioners of santería). The drawings on view at LUAG represent work created during Lam’s brief time in Cuba between 1940 and 1955, while the majority of his career was spent in Europe.

In 1923, Lam moved to Spain to continue his artistic studies at the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, eventually fleeing to Paris in 1938 after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (in which he briefly fought). During his time in France, Lam met luminaries of avant garde art like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse, and Georges Braque. Thanks in particular to his close friendship with Picasso, some critics have minimized Lam’s artistic autonomy, reducing him to an exotic foreign footnote in European art history. However, as Lam himself has said, his “painting is an act of decolonization,” and he has “worked in both directions” between Africa and Europe.**

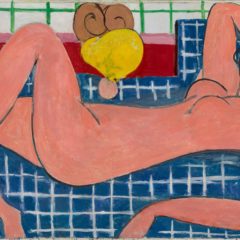

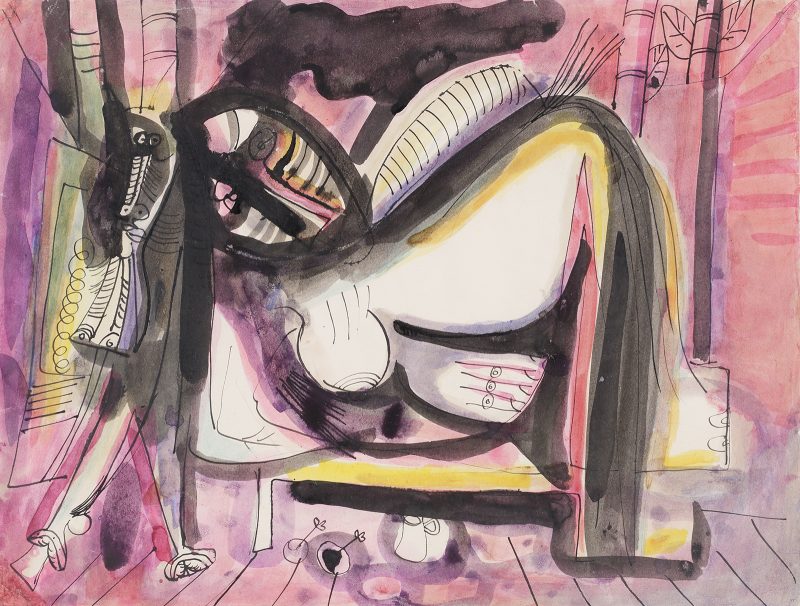

This give-and-take between traditions can been seen in Lam’s “Mujer-Caballo Reclinada,” (Reclining Horse-Woman) of 1946–47. Against a background of brilliant pinks and yellows, a woman reclines on what appears to be a bed, while another, smaller figure stands beside her. Straight, regular lines extend from beneath the bed towards the edge of the paper, suggesting wooden floorboards that place this scene in a domestic interior. A small pitcher under the bed underscores this impression, but tall bamboo trunks in the background suggest instead an exterior setting. This composition evokes the Classical tradition of the reclining nude, famously reconfigured by Edouard Manet in his “Olympia” (1863), which includes the figure of an African woman servant. Lam upsets our expectations of this imagery through his mixing of human and animal, African and European imagery, while never subsuming one into the other. The reclining woman has what appears to be a horse’s tail, while the figure accompanying her has a long horse-like head. The reclining woman’s face has been rendered as a mask that stares directly out at the viewer. Rather than the white bodies beneath the African-inspired masks of Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Lam’s reclining woman seems to merge with the mask; there is no contrast between the body and the mask. It feels like Lam understood the function and meaning of African art in a way that his European contemporaries did not, which gives his work depth and resonance–definitely not an art historical footnote.

Recurring motifs appear again and again in these drawings–the horse-woman, crescent moon, and bird. These personal hieroglyphs come together in the deceptively simple line drawing, “Figura con luna” (ca. 1947), which, according to Castillo Vázquez, used to hang in Lam’s studio. The artist’s great-nephew read an autobiographical poem by Lam describing how he awoke one morning at age 5 to see the shadow of a sleeping bat, feeling as though his room had been turned into a magic lantern, producing monstrous two-headed creatures, the inversion of familiar reality. In “Figura con luna,” we see a two-headed, winged horse at the bottom of the frame, and above it the torso of a woman surmounted by two abstract forms that might be heads. In the upper right corner of the drawing, floats a crescent moon that looks like a woman’s face, her eyes closed–the eyelashes precisely delineated–and face peaceful. The moon has a small curved horn, similar to the spiky horn-like protrusions on the other figures in the drawing. This mix of human, animal, and plant imagery–all with a sexual undercurrent–evokes the complex sensory landscape of his childhood, suggestive, shifting, and dreamlike.

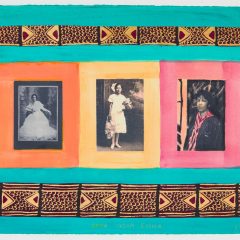

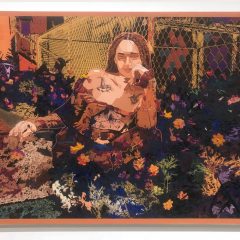

Lam’s drawings are juxtaposed with a show of work by contemporary Cuban-born artist Maria Martínez Cañas, whose photographic collages show a clear debt to Lam, and suggest his lasting legacy in Caribbean art. Fortuitously, the LUAG’s teaching gallery immediately across from the small gallery housing Lam’s drawings is filled with with African objects like an antelope-shaped Bamana headdress, whose echoes can be clearly seen in the stylized animal forms of Lam’s drawings. Looking forward to contemporary art and back to the art of the past, Lam’s influence and inspiration is clear.

** “‘My Painting is an Act of Decolonizaton,’ an Interview with Wifredo Lam by Gerardo Mosquera (1980),” translated by Colleen Kattau and David Craven, Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 3.1–2 (2009), pp. 1–8.