Finding the Hidden City, in two parts — City of Infinite Layers and City of Living Ruins – is an archeological and architectural journey, a palimpsest through “infinite layers” of the life of Philadelphia as reflected in its structures, institutions and social fabric, past and present. The book presents a brilliantly cross-referenced, significant slice of the modern history of the city, much of which is likely unknown or overlooked by the lion’s share of its inhabitants.

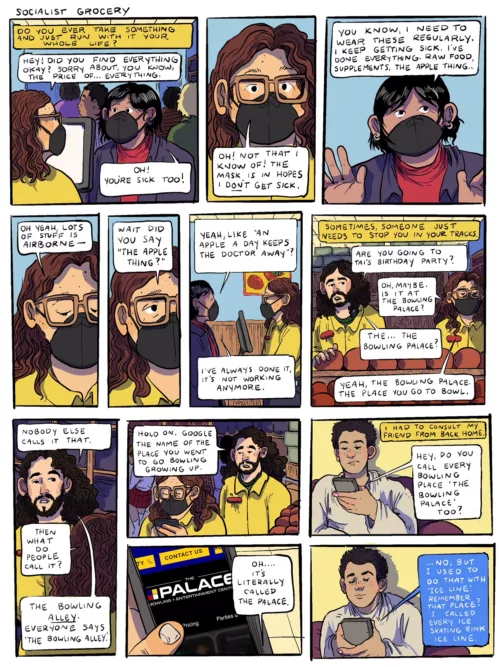

The hearty stew of intriguing subjects touched upon in the book includes the footprint and fate of Philadelphia’s “hereditary aristocracy;” the overlooked history of the African American community; the history of manufacturing and deindustrialization; mass transit and the railroads; segregation and white flight to the suburbs; the Catholic Church; immigration; the city’s cultural heritage; and what the authors call “cultural reticence.”

Why Hidden City? Sleuthing to uncover how Philadelphia differs from other cities

Popkin and Woodall, who also created the online publication called “Hidden City Daily,” which advocates for historic preservation, borrowed the expression “hidden city” from Nathaniel Burt’s The Perennial Philadelphians (1963). According to the authors, Burt compared Philadelphia with “forward-looking” cities, and he concluded that the city’s uniqueness was a function of being “too inward, too drowsy, and too parochial.” They quote Burt, who first articulated the notion of the city’s hiddenness:

“It was neither exciting like Manhattan, quaint like Boston, nor picturesque and glamorous like the South and West. It was not even conspicuously awful like the Midwest. It was, in fact, like some forbidden Oriental city . . . surrounded by its own impenetrable wall.”

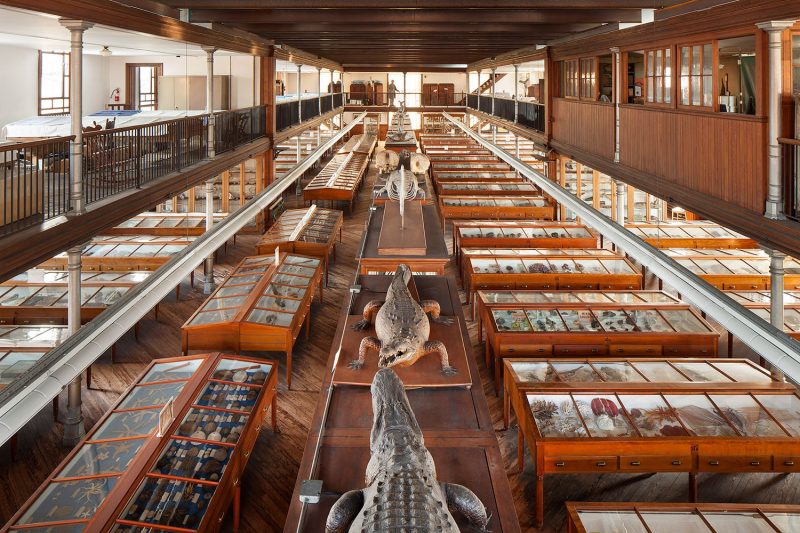

According to Popkin and Woodall, the notion of a “Hidden City” still rings true a half century after Burt’s work, because “Philadelphia seems to possess an exceptionally large number of places that have disappeared elsewhere – workshops and small factories, sporting clubs and societies, synagogues and theaters and railroad lines – like endangered species that have managed to stay alive in some remote forest or swamp.”

Their book, they suggest, seeks to capture the hidden soul of Philadelphia.

Digging into architecture and segregation/integration at Girard College

Just one example, from among hundreds, is a small section devoted to Girard College, part of magnate Stephen Girard’s legacy to the city. After describing the architectural history of the school (under the influence of financier Nicholas Biddle, who apparently had a thing for Greek Revival), the book turns to the history of the school’s racial integration.

As the book recounts, Girard, one of the richest men in America, intended the institution to serve “poor, male, white Orphans.” He also prescribed in his will that the school was to be surrounded by a wall – “fourteen inches thick, and ten feet high.” After the school opened in the middle of the 19th century near the Eastern State Penitentiary, the surrounding neighborhoods were populated primarily by white Catholics of Irish and German descent. In the 1930s, and during the early years of the Great Depression, there was increasing and considerable poverty in those neighborhoods, beyond Girard’s wall, and they became largely African American.

In the 1960s, Cecil B. Moore, a prominent black lawyer who then was head of the Philadelphia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, launched a campaign to integrate Girard College, to open it to the poor black boys (and later to black girls) who lived beyond its walls. Moore relentlessly led protests at the school. Indeed, one of them was attended by Martin Luther King Jr., against Moore’s wishes – he apparently disagreed with King’s commitment to nonviolence. Eventually Moore filed a federal civil rights suit and prevailed. The court broke Girard’s will, and integrated the school.

The intricate narrative of Finding the Hidden City is beautifully written, even lyrical. The authors, who were first inspired to explore Philadelphia by “the beauty we find in decay and the melancholy it evokes,” have pulled together a vast amount of material, and have done so with impressive, scholarly thoroughness and thoughtfulness. And the photographs are spectacular. There are so many complicated, fascinating, interrelated themes introduced, and presented in astounding, rich detail (with references and citations intermingled within the text), however, that the result can feel, at times, overwhelming.

Finding the Hidden City accordingly is not light reading, but it makes a significant contribution to understanding this great city, and, like exploring one’s ancestry – a task which so many of us often neglect and end up regretting – the exercise ultimately is enormously enriching.

Nathaniel Popkin and Peter Woodall are the co-founders of the web magazine Hidden City Daily https://hiddencityphila.org/. Popkin is a writer and critic, Woodall a former journalist. Joseph E. B. Elliot is a Professor of Art at Muhlenberg College and an Instructor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City is published by Temple University Press. The authors have produced a video in which they speak about the book.

[Ed. Note: Artblog is a collaborating partner with Hidden City on occasional art and history tours.]

Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City

Nathaniel Popkin, Peter Woodall and Joseph E.B. Elliott

$36.95

192 pp

7.875 x 10.5

102 color photos, 8 halftones

Published by Temple University Press

Available through Hidden City