Galerie St. Etienne, whose roots lay in Austria, was rebirthed in America following its founder’s flight from the Nazis in 1938 and subsequent emigration in the U.S. Unlike other Manhattan galleries (or most galleries, period) Galerie St. Etienne embraces political commentary.

“All Good Art is Political”, the current show, is full to the brim with politics. The two-person show juxtaposes the work of Käthe Kollwitz and Sue Coe, two highly regarded and highly political artists who were born nearly a century apart but whose work springs from a similarly compassionate perspective. German-born Kollwitz (1867-1945) is legendary in the art world, best known for her print work and charcoal drawings depicting the poor, working class, and those affected by World Wars I and II. Kollwitz is one of the few female artists to attain political and artistic recognition during her time. Sue Coe (b. 1951) is a British-born artist and activist whose work is inspired by Kollwitz and succinctly captures today’s social and political turmoil in its own right.

The burden of women and children

Kollwitz did not align with any of the dominant political parties of her time due to the ethical shortcomings she perceived on all sides. Also, according to the gallery essay, her concern was far broader than what the political parties talked about — the shortcomings of society and struggles of the oppressed — “food shortages… the plight of prisoners, the poor and, as always, the extra burden shouldered by women and children.”

Hunger (1922) is a tormenting image of female burden and desperation, a monochrome woodblock print of a screaming, starving woman, with a child in her lap that looks more skeletal than alive. The mother wears a tattered black robe with her emaciated body and breasts peeking through. The child wears nothing, which emphasizes the ribcage and bloated stomach.

The Survivors (1923), a charcoal drawing that was later turned into a woodblock print, powerfully shows a woman with a group of children huddled around her in the foreground, while in the background looms a group of sickly looking men. The mother and several children look to the viewer with agonized eyes while the men in the back look to the mother with varying expressions. This image of desperation references survivors of World War I and, according to the gallery essay, depicts women in the aftermath of destruction and displacement, “protecting their children just as animals do with their own brood.”

“If people know the facts, they’ll change the system”

Kollwitz created images from events that are — for the contemporary viewer, at least — a lifetime away. While the German Expressionist style makes them skew “old,” deconstruct the images of hunger, starvation, and the ruin of war and they are eerily in tune with today’s front page stories of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the refugee crisis, and hunger and starvation in many war-torn countries. The issues Kollwitz cared about are equally present in our world in 2017.

Sue Coe’s art is based on events that are more contemporary and thus much more familiar to the majority of viewers today. She, like Kollwitz, illustrates oppression, injustice and cruelty she has witnessed in the hopes that, “if people know the facts, they’ll change the system”, according to a quote by her in the gallery essay. Traffic Violation (1986), is an oil painting depicting men being beaten with bats by three police officers. The piece reflects an issue of racial profiling and police brutality against people of color in America that has not ceased or slowed in the three decades since its creation.

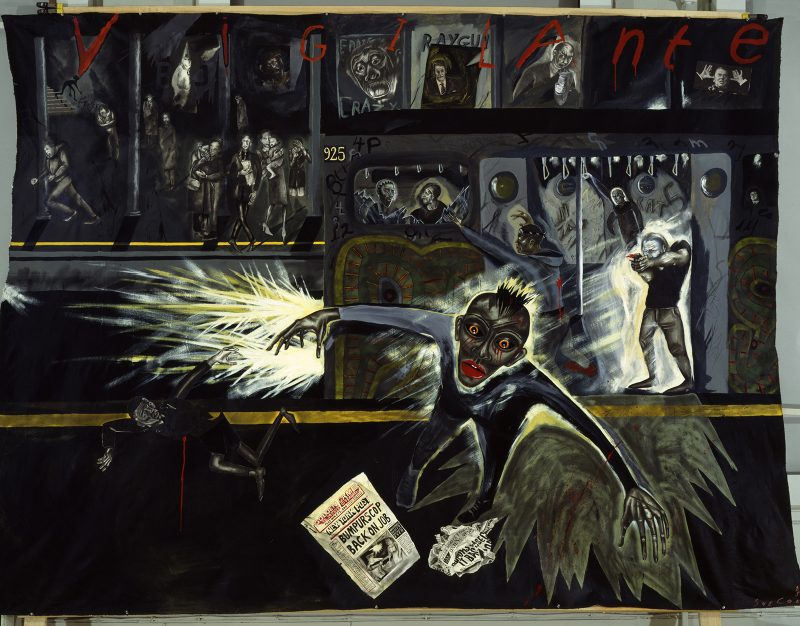

In a similar vein, the gigantic mixed media collage and painting Vigilante (1985) is based on the 1984 NYC “subway vigilante” Bernard Goetz, who, while riding the subway, shot a group of black teenagers, claiming they tried to mug him. It is a powerful, dramatic image, certainly for me one of the most memorable from the show.

But the work raises an issue that I am struggling with; who owns the right to paint other people’s pain? Similar to the controversy surrounding Dana Schultz’s portrait of Emmett Till at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, I have to wonder whether it is respectful for Coe as a white woman to depict these larger than life images of brutalized people of color. In context of her career’s mission to promote equality and ethical treatment of humans and animals, I understand. I also understand that this painting was made 30+ years ago, long before identity politics raised the issue of who “owns” whose images and who is allowed to paint what. Nevertheless I am struggling with the the image, knowing who made it, and feeling that it is insensitive to the people portrayed.

I like Coe’s work. I have great admiration for her long activist career and her dedication to giving injustice a wider audience in a mission to change the system, as she puts it. There are no contemporary depictions by Coe of racial violence in the show, and I am wondering why the gallery chose to put such an inflammatory piece into the mix. Perhaps it is to stir up discussion.

To bear witness to oppression

The show is expansive, including thirty four works from each artist and accompanied by a lengthy essay. Kollwitz’s desire to “bear witness” and “express… the suffering of human beings,” is mirrored by Coe’s intent to “help serve justice and highlight the oppression that is concealed”. Though I wouldn’t go so far as to say Coe is linearly continuing Kollwitz’s legacy in the manner suggested by the essay, I believe “All Good Art is Political” presents the two in a lovely sisterhood of solidarity.

“All Good Art is Political: Käthe Kollwitz and Sue Coe” is on display at Galerie St. Etienne (24 W 57th St, New York, NY 10019) through February 10, 2018.