Touko Laaksonen, an artist who worked under the pseudonym, Tom of Finland, lived in Helsinki in the middle of the 20th Century, in a society where his sexuality, and the erotic art work he created as an expression of his sexuality, were illicit. Indeed, it was a society in which gay men, and presumably women, were persecuted, often with violence, stigmatized, and pathologized.

Tom of Finland, the biopic about Laaksonen’s life – he lived between 1920 and 1991 – dramatizes the ways in which the Finnish community forced its gay citizens into the shadows, particularly in the years after the end of World War II. The story glides through decades of Laaksonen’s adult life, culminating in the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, but its emphasis, and its most moving sections, is upon his experience in World War II and his life in post-war Helsinki.

Homophobia in post-war Finland

Homosexuality was illegal in Finland during those years – it remained a crime until 1971, and its “promotion” (through art or otherwise) was illegal until 1999. Romantic or sexual connections between gay men were limited to furtive glances, to bathroom stalls and secluded public parks which were frequently raided by the police, who subdued and often beat and arrested the men they managed to capture, at least when the same police were not participating in their “crimes.”

After the war, in addition to producing a corpus of homoerotic art which, at the time, was illegal to purvey in Finland, Laaksonen tried to form relationships with other men. He persevered, but his efforts often were foiled. In one episode of the film, Laaksonen puts together postcard-sized examples of his erotic art work and uses them as calling cards. In the bathroom of a nightclub, he slips one between toilet stalls, where he is being set up by a patron who has pretended to be interested in him. Laaksonen ends up beaten and expelled from the club. In another episode, during a trip to Berlin, his identification papers and his work are stolen and he is arrested, only to be rescued by a Finnish official, a married, but closeted gay man who befriended him during the war. While under arrest, a disgusted German police officer grimly reminds him that during the war, people “like him” were sent to the concentration camps.

During the post-war period, Laaaksonen lived in Helsinki with his sister, who helped him find a job in an international commercial advertising agency, McCann-Erickson. His sister was a sympathetic person, but she had not overcome the pervasive national homophobia. She loved her brother, and she hoped that he would find a girlfriend. In one telling scene in the film, at a party, she presses him into a game of spin the bottle, and eggs him on to kiss one of the women in the circle. Laaksonen, the good (closeted) brother, complies. He later lived openly with a male lover, Veli, who was a dancer. Their relationship ultimately was accepted by his sister, and it lasted many years, until Veli’s death.

PTSD

One recurring theme in the film involves a traumatic incident from the war. Laaksonen served in the military when Finland (then aligned with the Nazis) was at war with Russia, and after the war he suffered from night terrors. In the scene, Laaksonen is seen alone in the woods. He is urinating. He spots a rabbit nearby, and smiles. Then he sees a Russian paratrooper fall from the sky into a field nearby, and he runs out into the field and stabs the man, killing him. The film flashes back to this incident a number of times, suggesting the extent to which Laaksonen was haunted by it after the war. But what to make of the rabbit? Laaksonen actually was a glass-half-full guy, so perhaps his memory of the rabbit mitigated painful memories of other wartime experiences.

Los Angeles and beyond

In the 1960s, Laaksonen eventually found an outlet for his work in Los Angeles, where it became a regular feature in Bob Mizer’s popular gay underground magazine Physique Pictorial. From there, his fame as a counterculture hero in many gay communities spread to New York and hence around the world.

There is a wonderful episode in the film which takes place in LA, where Laaksonen and his local troupe are searching in vain for a publisher for his work. Eventually they find their way to an elderly orthodox Jewish man, who ran a small publishing firm with his daughter. This brave man was willing to take on the (probably illegal) project, but he lacked the manpower to do it. So Laaksonen and his compatriots go to work there, and the rest is history.

The art of Tom of Finland

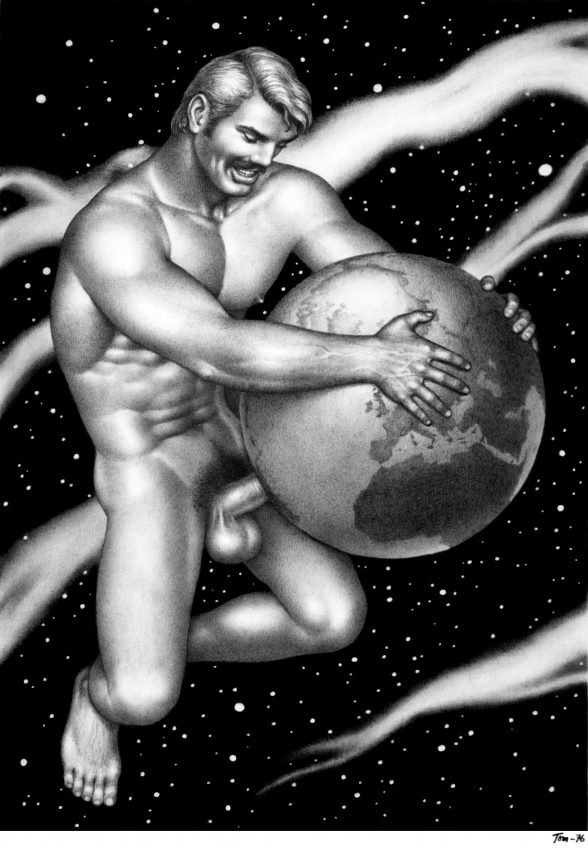

As Tom of Finland demonstrates, not only was Laaksonen a survivor, he somehow remained an optimist through it all. The film does not focus on his work — although many examples of it appear – and it’s worth mentioning that the same optimism dominated his drawings. Included below is an image of one of his untitled pieces, from 1976, which is a typical example of his large body of work. This drawing was exhibited in a retrospective in 2015 at the Artists Space, in New York, titled The Pleasure of Play, which we covered. Note that Laaksonen’s beefcake protagonist in the piece, who very well, and justifiably, may be saying “fuck you” to the world, is saying it with a smile on his face.

“Make sure everyone knows we exist.”

Something about Laaksonen – perhaps his good-naturedness — reminded me of Harvey Milk. But he was not a political activist, as Milk was. Indeed, there are suggestions in the film, and elsewhere, that he was far more focused upon symbols of homosexuality, both in his personal life and in his art, than he ever was in politics. He was, for lack of a better term, an activist for the open representation of eroticism in gay culture. As such, of course, he played an important part in the movement towards gay liberation.

Laaksonen’s long time partner, Veli, died around the same time that Laaksonen was achieving some fame and notoriety overseas. Before he died, he said to Laaksonen, “Make sure everyone knows we exist.” And Laaksonen did.

Tom of Finland is directed by Dome Karukoski. Aleksi Bardi wrote the screenplay. Pekka Strang brilliantly plays Laaksonen. The film is Finland’s official submission to the 90th Academy Awards, and will open on November 24 at the Ritz at the Bourse.

Although the film does not break any new ground, and glosses over long periods of Laaksonen’s later life, it is engrossing and, of course, also disturbing – overall a fine celebration of this man’s life and of the contribution he made through his art work to emerging gay communities everywhere.