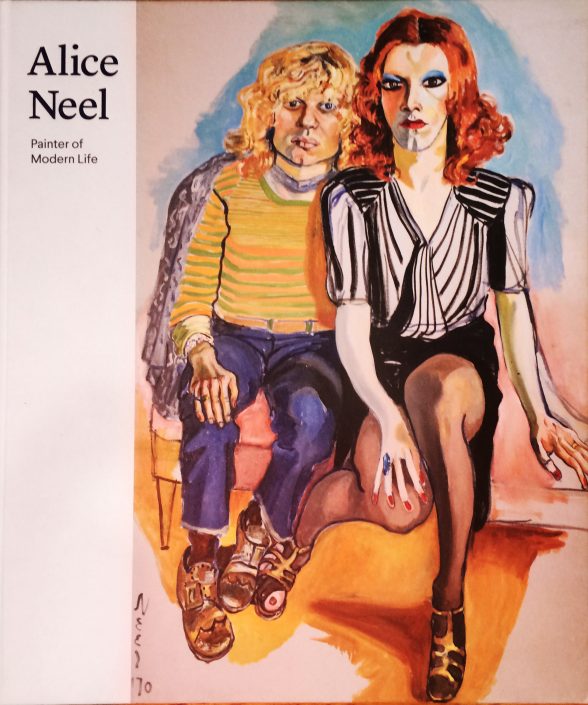

Lewison, Jeremy, ed. “Alice Neel; Painter of Modern Life”

Mercatorfonds and Yale University Press, Brussels and New York: 2016

ISBN 978-0-300-22007-0

$42, plus shipping

Available on Biblio

For fifty years Alice Neel pursued her own path, not attracting widespread attention until the last two decades of her life. Her style was highly individual and her favored subject – portraiture – was unfashionable. Neel’s emotionally revealing, expressively-painted works constitute an inimitable record of New York City residents from the 1930s until her death in 1984. Few of her portraits were commissioned by the sitters. They were the product of Neel’s penetrating engagement with people she chose to paint, some of them strangers. She depicted her neighbors, fellow artists– Andy Warhol asked her to paint his portrait– art historians, writers, political activists and her family.

The artist was born in 1900, raised outside Philadelphia and attended Moore College of Art. After moving to NYC she mixed broadly in artistic, intellectual and Communist political circles. She painted her black and Hispanic friends and neighbors, cross-dressing downtown performers and impoverished, left-wing writers with the same respect she accorded major taste-makers in the art world. Her unprecedented portraits include gay couples and pregnant women in the nude, and she was unsurpassed in painting babies and children with the same incisiveness as adults. Although she exhibited regularly in group and occasional solo exhibitions, she was 62 when the first, substantial national article about her work appeared.

This well-designed and produced catalog for an exhibition organized by The Ateneum Art Museum/The Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki provides an ideal survey of Neel’s paintings. Outside of special exhibitions her work can only be seen one painting at a time, if at all. This volume includes a number of her best-known works including portraits of Andy Warhol, Joe Gould, and the nude self portrait painted when she was 80, as well as examples of her still lifes and cityscapes.

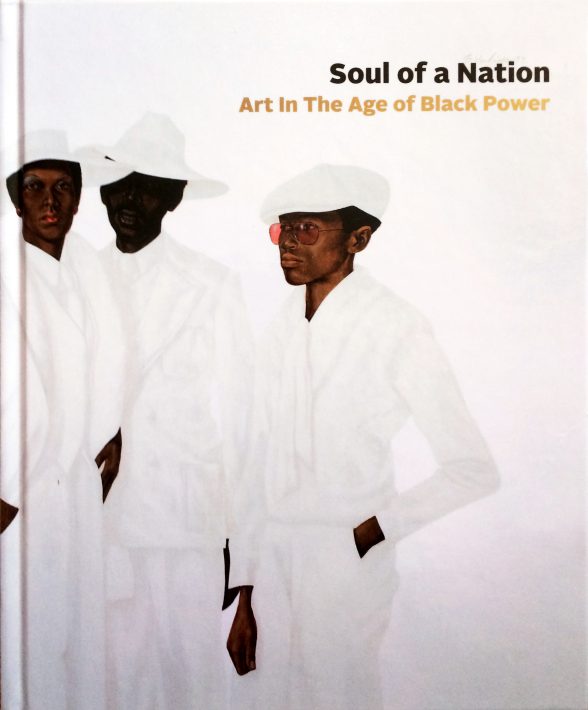

Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley, eds. “Soul of a Nation; Art in the age of black power”

D.A.P. Publishers, Inc., New York: 2017

ISBN 978-1-942882-0

$28.29, plus shipping

Available on Amazon

This is the best overview I know of art by and about African Americans during the 1960s-1970s and includes excellent and extensive illustrations of its subject. It was produced as the catalog for an exhibition organized by Tate Modern, London that will travel to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in February, 2018, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art in September, 2018. Godfrey and Whitley have done extensive research and talked with most of the scholars, curators, artists and other interested participants of the period; their excellent essays – Godfrey on abstraction, Whitley on figuration – reflect a broad perspective. They are supplemented by short contributions from Susan E. Cahan [Ed. Note: Cahan is the new Dean of Tyler School of Art], Edmund Barry Gaither, Linda Goode Bryant, Jae and Wadsworth Jarrell and Samella Lewis.

“Soul of a Nation” covers a wider range than recent books and catalogs with which it overlaps and whose scholarship it credits; these were devoted to the art of black Los Angeles, artists who produced the influential “Wall of Respect” in South Chicago, art that addressed the civil rights movement, black performance artists, exhibitions devoted to abstraction during a period when vocal groups from the black community desired affirmative imagery that advanced civil rights, and black artists who lobbied NYC museums for greater representation. It covers painting, prints and sculpture as well as photography, illustrated books, posters and other ephemeral media, performance art and film. The book is attractive and well organized.

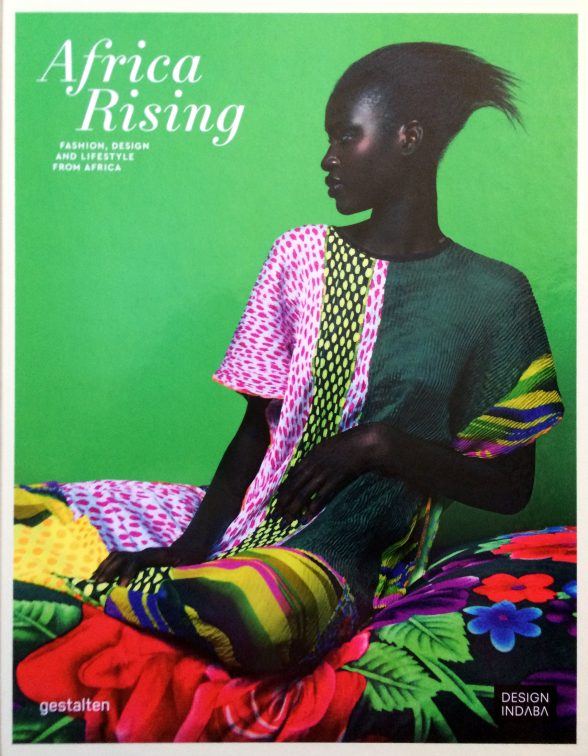

“Africa Rising; Fashion, design and lifestyle from Africa”

Gestalten, Berlin: 2016

ISBN 978-3-89955-641-4

$40.80, plus shipping

Available on Amazon

This extremely alluring book presents a compelling array of design for interiors, architecture, fashion and household furnishings as well as several artists’ projects from individuals and collectives across the African continent. Some of them studied or worked in Europe or the U.S., others entirely in Africa, but the work is clearly intended for a sophisticated, international audience. All the designers interviewed choose to reflect their work’s origins through some combination of local motifs, traditional craftsmanship and/or locally-sourced materials.

The text has the promotional tone common to fashion and decorating magazines, and the illustrations reflect the same sources. They are gorgeous and extremely seductive. The authors are anxious to dispel the largely-negative impression of Africa presented by traditional news sources. Readers will have to decide for themselves whether, in the several instances given of white South Africans adopting motifs from tribal groups or employing tribal craftsmen, they are supporting indigenous populations and helping them maintain their traditional crafts or merely exploiting them. The book is not a study of the politics and economics of using local materials and craftsmanship to produce luxury goods for export — but does not pretend to be. Nor does it describe the extent of production or distribution of the work. But it is certain to send readers to the internet to find outlets for many of the stunning and intriguing designs it illustrates.

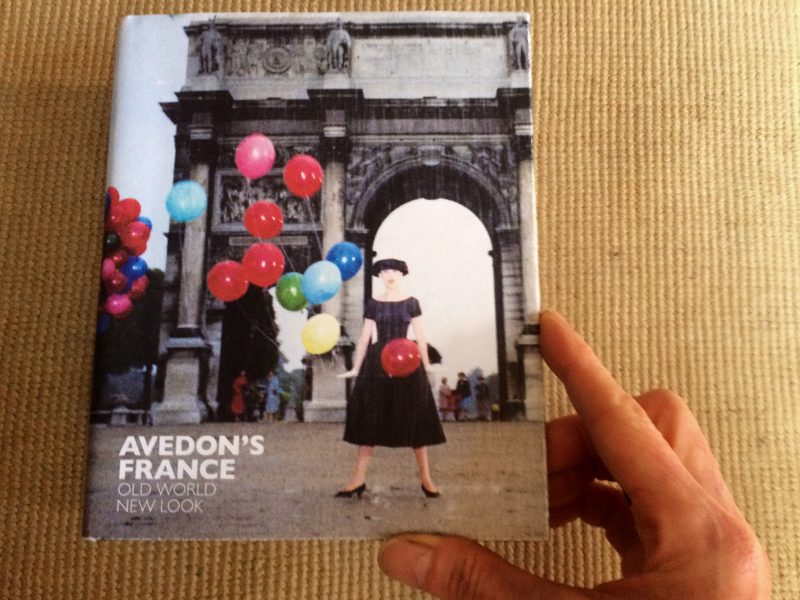

Robert M. Rubin and Marianne Le Galliard, “Avedon’s France; Old World, New Look”

Abrams and Bibliothèque nationale de France, New York and Paris: 2017

ISBN 978-1-4197-2600-2

$30.35, plus shipping

Available on Amazon

This publication documents Richard Avedon’s love affair with Paris which dates from the start of his career and continued throughout his life. Whether perused for its images or read for its texts it will appeal to readers interested in photography, vintage fashion, 20th century French culture and the interaction between European and American culture in the decades after WWII.

Avedon was sent to photograph French couture at the debut of the famous New Look which followed wartime austerity. It was a period when Americans thought themselves provincials and believed that everything serious in fashion and culture was happening in Paris. He might have been whistling the post-WWI song,”How Ya Gonna Keep ’em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree?)”

This catalog to an exhibition at the French national library covers Avedon’s fashion work, his photography for and art direction of the film, “Funny Face” (1958), which was based on his own experiences, his promotion of the French photographer, Jacques Henri Lartigue, and his documentation of a generation of French intellectuals and cultural figures who rose to prominence between the wars. The director of the Bibliotheque Nationale says proudly that his institution has long considered Avedon as more than a fashion photographer. Significant essays and interviews take the range of the photographer’s activities seriously even as they discuss his insecurity about both the commercial beginnings of his career and the questionable status of all photography. The design by COMA is surprising and inspired; small and chunky when most photography publications continue to grow, it fits well in the hands and contributes sensually to the visual and intellectual pleasures the book offers.