Icon of the Infinite Scroll

By Leah Gallant

1.

I used to believe that by writing about art you could give a picture teeth.

I thought images were silent, expansive, atmospheric; writing was finite, sharp, something fundamentally useful. I thought that writing could goad a picture into holding a particular meaning. The pen was like a scalpel, or a cattle-prod, or something.

It was never quite true. Writing was never my medium. The medium is string. I am trying to tie one thing, like what someone is shouting, to something else, like someone’s ear. Or: the medium was never writing, it was banging stuff together.

I am trying to bang one picture of a shipwreck to another picture of a storm.

2.

It is like an alternate version of the Last Supper. The long table is heavy with food: canned goods, boxed pasta, maybe some Twinkies. (The fish is now tuna-cans, the loaves are now pasta). The perspective has changed. The scene is not viewed head-on but from its side. From this angle Judas looks like a populist hero.

There is a cross in the back left, the words ‘Mary Chapel, Puerto Rico’ projected onto the wall.

All the tension in the image is in the roll of paper towels hovering mid-air. It is like the Holy Spirit descending in a quiet blaze of light. Everyone is looking up. Their hands raised to photograph the scene look like hands raised in prayer.

He was panned for this, of course. He spent a little more than four hours on an island, in which he applauded himself for his relief efforts, and, in a crescendo of goodwill, threw paper towels into the crowd at a church. If a resort can be a meeting place for heads of state I guess it makes sense to treat a natural disaster like a halftime show. The logic, I guess, is that the paper towels could if not restore power or provide potable drinking water, they could be used to clean a flooded kitchen.

“They had these beautiful, soft towels. Very good towels,” Trump told Mike Huckabee during an interview Saturday with Christian network Trinity Broadcasting…“And I came in and there was a crowd of a lot of Jonathan Ernst / Reuters people. And they were screaming and they were loving everything. I was having fun, they were having fun,” he added. “They said, ‘Throw ’em to me! Throw ’em to me Mr. President!”

There is such a biblical cadence to his speech, washed clean of any words longer than two syllables. He starts consecutive sentences with the word ‘and,’ as though everything were prophesied. Subjects are either good or bad, with additional descriptive options for women and other items.

Only his usage of the word ‘sad’ seems thoroughly modern.

3.

![Icon of the Infinite Scroll, A Winning Essay in the New Art Writing Contest! 2 Jonathan Ernst / Reuters [detail]](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/2017/12/artblog-leah-gallant-icon-2-800x468.jpg)

Each grouping seems preordained. Each cluster of bodies emits its own sort of heat.

They are separate from the main event. In the left, one man leans in towards another in purple. The placement of his hand, on the man’s lower back, is so tender, so intimate. Two men touch each other while the president throws.

On the right, two people turn to face each other. One of them has just caught some paper towels. Were they loving it? Were they loving something else? It is true that in a crowd of fifty people, two of them smiled.

4.

An icon displayed in a museum can flash and disappear like an image in a newsfeed.

I was looking for my favorite painting in the museum, if not the world, and it was not there. I had only twenty minutes before I had to get across town for my class and I had paced the hall of icons three times and it was not where it was supposed to be. I had to see it in order to conjure something to say about it but I could never predict what that thing would be.

They were setting up for yoga in the Romanesque chapel. People flicked through their phones and stretched in vague directions. Two guards stood near an image of a saint with a cleaver in his head, their hands in their pockets. They conferred quietly, like a side note to a larger narrative arc. They leaned towards each other in the hush of their talk.

It was not there. It had recently been removed from these galleries, one guard told me, in preparation for its resurfacing in November. It would be part of a show of the collection of John Graver Johnson.

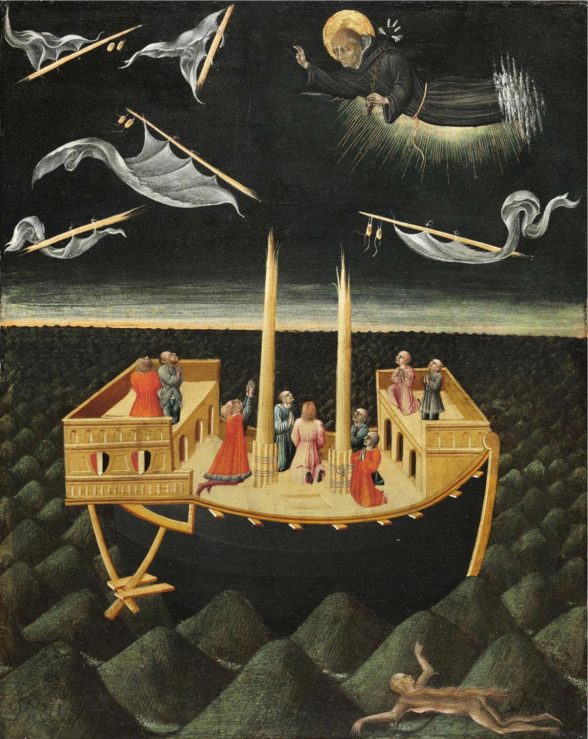

In my painting, St. Nicholas of Tarantino floats in the sky above the shipwrecked sailors. It is mid-storm, and the sky and the sea are a crazy green-black. The pieces of the broken mast have been rationed, one to each section of the sky. And the masts are like toothpicks, and the flying pieces do not correspond to the stumps of mast, it is impossible to see how the shattered thing was ever whole.

The sail-cloth is as flimsy as a ballot.

And everyone looks up. The saint has appeared in a blaze of tooled gold. One sailor has raised his arms; the others pray. The air is dark with nuclear fallout. A nasty woman lurks in the sea. She is nasty because she has spoken. The waves are like mounds on a private golf course. The patrons are rich people, so they get painted into the image. The saint appears in a flash of cameras. He is bigger than everyone else, he is almost the size of the ship. And he wears a dark suit and around his head is an orange sheen.

Sources

Silva, Daniella. “Trump Defends Throwing Paper Towels To Hurricane Survivors In Puerto Rico.” NBC News. October 8, 2017. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/trump-defends-throwing-paper-towels- hurricane-survivors-puerto-rico-n808861

Leah Gallant is an artist and writer from Cambridge, MA. She graduated from Swarthmore College in 2015 with a double major in Sociology/Anthropology and Studio Art.