The Psyche and Space

More Than Private at Slought

By Michael Carroll

One might expect to see isolated figures or remote spaces when visiting a show called More Than Private, but instead Carrie Schneider’s artwork presents intimate environments of varied occupancy. Her photography and videos explore the human psyche as it relates to the body within tense scenes of intertwined limbs and in subdued spaces where subjects are engrossed in their books. There is a common thread of sensuousness in her photos and videos that skirts voyeurism as to suggest locations of solace and contemplation. As a whole, More Than Private is a somber, meditative exhibition that digresses into a heady examination of space.

Curator Kaja Silverman elucidates the viewer’s experience with detailed wall text installed throughout the two rooms and with the exhibition culminating in a video series set to music. The series’ Reading Women and Dance Response Project approach the ego via polarized means of hyper focused reading and interpretative dance, respectively. Even still, there is a quiet drama at Slought that you experience while watching the seemingly silent video, Burning House, only to be overwhelmed by Kanye West’s “Blood on the Leaves” to your left. Despite this momentary conflict, the dynamic between the photography in the other galleries is complementary and engaging.

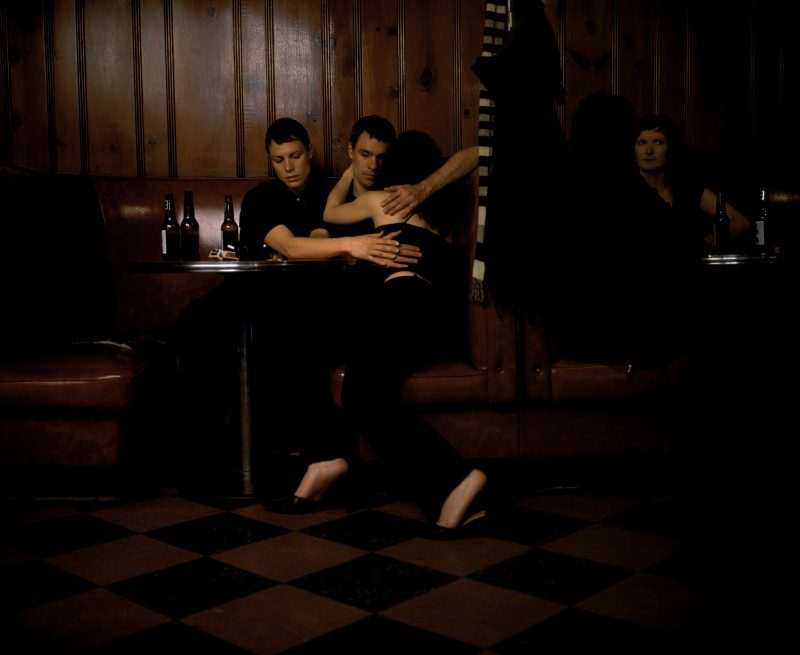

While there is a contemporary feminist lens in Schneider’s artwork, there is also a definitive element of the seventeenth century baroque with its flare for the dramatic. This is most apparent amid the strained sibling portrait series called Derelict Self. Untitled (Woodchips) from this series is classical in its composition with the wrestling figures who call to mind one of Caravaggio’s saintly scenes and evokes a sense of struggle between sibling pair. Untitled (Bar) and Untitled (Cafeteria) similarly focus on the brother’s and sister’s bodies in questionably intimate exchanges that Silverman describes as the “incest taboo.” However, this intimacy read more so as mimicry, or a familial collective consciousness surrounding memory rather than incestuous relations. As such, Derelict Self portrays a physical embrace of a far off trauma that has since grown into a fetishized nostalgia reenacted in a campy, yet artful manner.

In a similar baroque vein, the Dance Response Project video series highlights the human form in motion with music that ebbs and flows from fluid motions to heated crescendos of sensual engagement. The five videos feature dancers responding to music in solo and paired improvisations. At first the duets come across as sexually driven, but dissolve into meditations on the intimacy of touch and the relation of bodies in space. This manifests as a male and female couple resonating off of and around one another’s bodies in one video, while another features two men’s torsos and waists lustfully dancing as if they are in a club. Regardless of the pairing, they refocuses our attention on the syncopation and rhythm of dance as a shared experience that manifests the otherwise faceless figures’ relationship in that particular moment.

There is a simultaneous subdued passivity inherent in the viewer’s voyeuristic presence amid More Than Private. The video Burning House shows a small home set ablaze season after season without intervention. Schneider’s repeated construction of this home in Wisconsin is a meditation on the superficiality of physical space. Her routine destruction of this structure exemplifies the temporality of the commodities used to construct the home space. As the home burns, it is quickly diminished by the natural grandeur of its surroundings. The white smoke from the fire is quickly lost in the gray sky above, thick, dark smoke billows and dissolves into the tree line on the horizon, the bright flames of the growing fire blend into the vibrant orange and pink skies, and each season brings its own nuances to the ritual. Burning House finds beauty in nature and blatantly destroys the conventional home, or domestic space, that has bound women for centuries in Western culture.

Our presence in front of Schneider’s figural artwork is anticipated by the subject who occasionally breaks the fourth wall and looks out to the viewer, but generally speaking we are welcomed into these intimate moments of vulnerability. One section of wall text claims that the artist exposes the subject’s psyche as to bring the inside outward. This clever idea is quite successful without feeling exploitative or aggressive. The longer a viewer spends with an individual image, the more engrossed in the subject’s head space they are liable to become.

That is perhaps the most exciting and rewarding aspect of this exhibition. Every image feels personal and conceptual without being contrived or cliché. More Than Private brings about a sense of collective consciousness as a result and in turn the figures act as relatable archetypes of lived experiences intended for a broad audience.

All of this is to say that More Than Private presents the private moments of the multitude. The artist grants viewers access to the autonomous spaces of the collective consciousness. Reading Women is a blatant example of this. The series includes large photographic prints on two walls and a video projection on a third. Silverman says that “Reading Women is about a group of readers,” but not in a book club sense. Instead there is a sense of individuality among the multitude captured in these moments—with the multitude consisting of the three women present in the room: the artist, the author and the reader. Each woman chose their own book written by a woman and read until “the perfect moment,” so to speak, came when Schneider would turn on her camera. The reader’s experience is described as a “trans-generational transmission” of information between women and promotes the idea of collective consciousness and shared experience.

Reading Women illuminates a private multitude where information sharing between women, with a racially inclusive scope, informs future generations of women, and we, as viewers, are invited to relate to these moments of absorption and interconnection. Schneider’s More Than Private embodies this mindset of visualizing the individual’s psyche and expounds upon the archetypal nature of lived experiences, anxieties, trauma and memory.

Michael J. Carroll resides in Philadelphia and works in the Digital Library Initiatives department of Temple University Libraries on diverse digital projects. He is currently enrolled in graduate school at Tyler School of Art studying modern and contemporary art history, with a focus on LGBTQ artists and queer theory, in hopes of continuing his career in the galleries, libraries, archives and museums field.