The 21st century art world brought us hundred-million dollar paintings, global art fairs and significantly, the now almost weekly pop up exhibition. Taking advantage of spaces that are temporarily empty to scratch the ever-present aesthetic itch, pop up shows allow artists and young curators to create “happenings,” generate quick, local sales, and experiment in ways galleries, museums and art fairs can’t afford to do.

A new and unusual pop up exhibition series organized by French artist Thomas Fougeirol is now bringing scraps, maquettes and artwork misfires fished out of various artist studios. Fougeirol calls these exhibitions “Intoto.”

“When people know I’m coming, they will sometimes prepare an Intoto object for me,” explained French artist Thomas Fougeirol. “But I always choose something else.”

Fougeirol along with co-curators Julien Carreyn and Pepo Salazar, has given the name “Intoto” to the unusual Pop Up exhibitions held in Paris, New York and soon Brussels.

The most recent Intoto took place in a ground floor studio off a cobblestone passage in Paris, and featured 40 objects in all including a range of photographic scraps, torn vintage wallpaper, a group of 20 wooden blocks glued together, and an odd box of tissues, wrapped in masking tape, sitting on the floor.

About the Kleenex tissue box, Fougeirol recalled a visit to see American sculptor Linda Matalon’s Brooklyn, NY studio to hunt up something for the exhibition.

“Her atelier was crazy clean – every product covered over with tape or paper to hide all brand names,” said Fougeirol. “She wanted no outside image pollution.” Fougeirol discovered however, a store-bought tissue box covered with masking tape. “It was a curious and beautiful object. An Intoto!”

“Intoto” is also the name ascribed to the unfinished prototypes, failed works, incidental objects and discards he literally picks off the floors, tables and walls of artist work spaces.

Each Intoto echoes the artist’s hand or aesthetic and invites further inspection. Removed from the context of the artist’s studio, the Intotos, usually no bigger than a dinner plate, are left alone to tell their mysterious stories.

“In the art world there is a significant difference between the finished product and the leftover – the scraps and missed opportunities,” said Fougeirol. “I try to choose something which is not specifically an art piece – not an artist’s signature work. We don’t exhibit drawings or paintings, but focus on photographs, in between objects and documentation.”

The Intotos are typically displayed as art objects but without wall labels. Arranged into small, but spare intimate work spaces – locales donated to the project – the exhibitions last all of a longish weekend. All works sell for 100 euros each, and most of the pieces, noted Fougeirol, have sold.

“All the money goes directly to the artist,” Fougeirol noted. “We’re not a for-profit gallery. We’re a nomadic, changing collection of artists.”

In many ways the objects become a flashpoint of discussion between Fougeirol and the artist. “I’m an interested observer of these fragments, a fetishist, an anthropologist.”

The artist-curator is also interested in democratizing – in a small way – the inflated economics of the art world for both the buyer and the artist. While Fougeirol argued that the standard 100 euros for any Intoto piece is still a substantial amount of money, it isn’t so much that a gallery worker can’t actually spend on a piece – even if that piece straddles the line between art and non-art.

“I like the movement of these works, the small prices, the collectors collecting what I’ve collected – the Intoto exchange.”

The Artist Curator

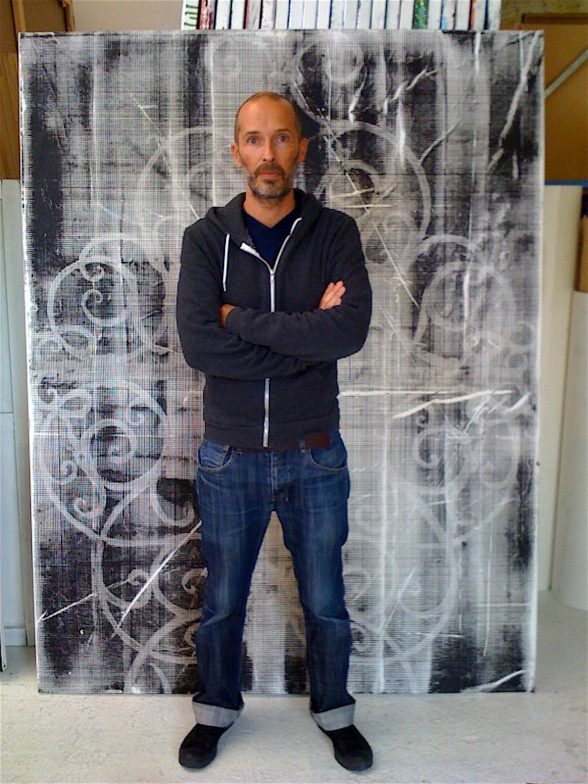

Fougeirol’s own works, which employ a range of objects that could be called Intotos, toggle between positive and negative, largely in black, white, silver and a variety of monochromes.

When I first visited the artist in Ivry-sur-Seine, a suburb just outside of Paris some years ago, I noticed a serious collection of plastic shower curtains, odd bits and pieces of bathroom hardware, and store-bought household items scattered about his studio. At the time, Fougeirol was using the curtains with their die-cut patterns to stencil and print all-over patterns on his canvases.

The Intotos offer insight into how the artist works, and to my mind they are analogous in meaning to, for example, the blackened pencil erasers and crumpled papers Albert Einstein used in his failed calculations. The Intotos, like Fougeirol’s own shower curtains, are atelier tools, used up throw-aways, and objects employed to generate images.

Anything could be used to produce art, Fougeirol suggested to me, asking pointedly and poetically: “What exactly is art anyway?”

Nomadic Exhibitions

The Intoto exhibitions began in an austere, Paris office in the Galerie Joseph Tang in October 2016; the second show in April of this year, took place in the Marais district of Paris in December a year ago. The third Intoto moved into a large salon at Le Molière, the classic French building where the 17th century playwright lived on the Rue de Richilieu in Paris.

“I’d met a woman who liked our project,” said Fougeirol. “She was friendly with the guy renting the space, and he offered us the entire ground floor salon to use for the weekend. A 300 square-meter space!”

The Intoto project was then invited to Essex Flowers, a Monroe Street space in Chinatown, New York this past June. “The tiny gallery, only 700 square feet, was a very Intoto kind of space,” said Fougeirol. “Intimate, raw, unusual and quirky.”

That exhibition brought more New York artists into the collective which now numbers nearly 100. Thus far, said Fougeirol, artists have come from France, The US, Spain, Italy, Poland, Lithuania, Catalonia, Australia, South Africa, Peru and an American-Japanese artist as well.

The last Intoto took place this past November (2017) in Paris – that’s where I saw the tissue box on the floor. It made me think about these fragments, their possible purposes and how the word “Intoto” somehow echos a religious chant or a nonsense sound uttered by a child– or both.

These bits of failed works that lined the walls each seemed to sound a unique note in an orchestra of pleasant white noise, perhaps in a similar way Duchamp’s “Readymades” did 100 years ago. Taken together they appear as anonymous totems, wandering religious icons that intrigue, as if you’ve discovered a new culture by tripping over it.

But stripped of their purposes, these Intotos are not objects of worship; rather they are turned into objects of interest, bits of evidence of mystery, belief, or memory, or the nascent efforts behind creation or defeat, rustles of wind that lift and die.

As an artist myself, I recognize the precious cast off in these exhibitions, and see that Fougeirol, too, values the overlooked and sees in them a kind of agape of possibility.

The next Intoto takes place in Paris in April of 2018 at the Fondation d’Enterprise Ricard [https://www.fondation-entreprise-ricard.com/en], a large exhibition space sponsored by the French drinks maker.

“I’ll be busy in 2018 collecting quite a few of these little magical objects,” said Fougeirol. “It’s good because it gets me out of my own studio.”