In Philadelphia, the desire for critical arts writing is shared by all but ultimately facilitated by few — here, writing and editing are labors of love. Without the economic incentives behind art criticism (as in New York or Los Angeles), most Philadelphia arts writers are themselves artists, who give their time to write because they believe it is fundamental to the community’s health. I was curious about the complicated roles that artists in Philly often play, and was excited to speak to artist-writers Julia Clift and Samantha Mitchell about their experiences on the occasion of their exhibition at Gross McCleaf, Here, We Are There, which ran November 1-25, 2017.

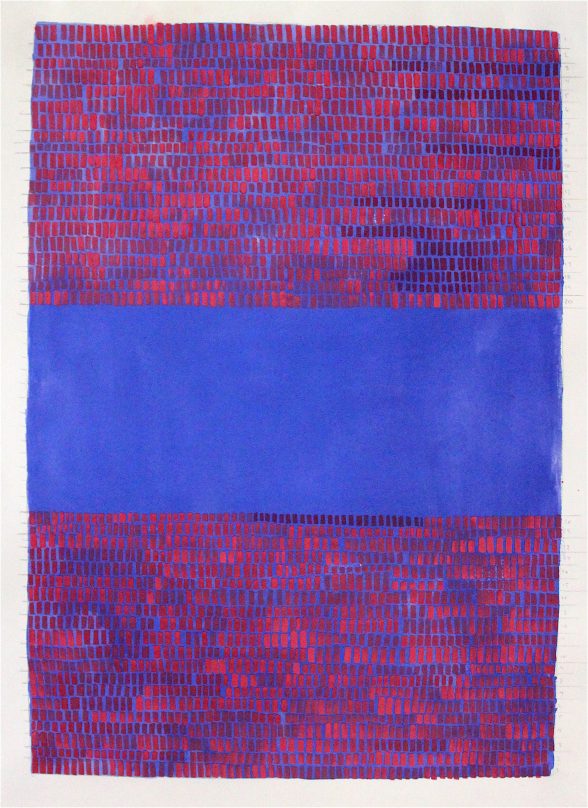

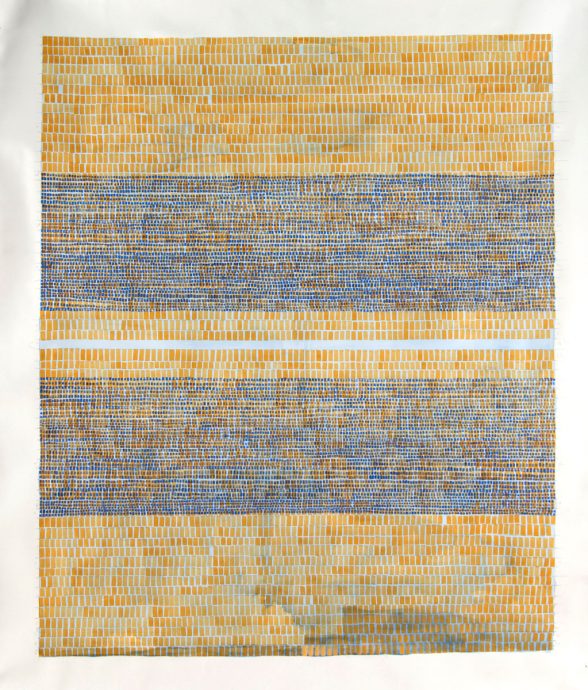

While, in the show, both artists wrangled with landscape, they also both have extended drawing practices around other subjects (see Clift’s Woman Drawings, and Mitchell’s Our Autonomy). In her most recent body of work, Mitchell depicts the wide, atmospheric spaces of the Oregon Playa with a tapestry of brush strokes. The marks rest against a careful grid, abutting, softening, and complicating the programmatic system those lines imply. Her subtle modulations of mark and color connote, without illustrating, the experience of a vast American landscape. Clift’s landscapes also utilize abstraction, but they feel intimate. On small panels, she paints the shallower space of a backyard — a garden, a fence, a hallway, a lawn — collaging plein air elements and carefully sanding the surfaces to expose sections of gesso. The resulting paintings are constructed with abstract forms that resist definition, yet feel incredibly specific.

Both Julia Clift and Samantha Mitchell are artists whom I first encountered as writers. Clift, a painter, educator, and writer who has published pieces with Hyperallergic, Huffington Post, and Title Magazine, writes about work exhibited both locally and nationally. Reading her concise and lovingly constructed analysis of Adam Lovitz’s enigmatic paintings made me feel closer to and more able to understand them. I think that is what good criticism should be — it should clarify meaning without assigning it. It ought to be written from a perspective of real care for both the artwork and for its own critical integrity. When I visited Clift’s studio in Lansdowne, PA, she told me one of her primary motivations in writing is to facilitate her own understanding of other people’s artwork — a way to “get at the juice” in a show.

I have known Samantha Mitchell since 2014, when I began writing for Title Magazine as an undergraduate painting major at The University of the Arts. In those days, the editors would trade responsibilities, and about once every five months, I had the pleasure of getting her feedback. Draft after draft, these documents full of subtle tweaks and thoughtful comments would appear in my inbox. Though until recently my interactions with Mitchell were purely over email, she taught me how to write in ways that school assignments never could. After working with her for several years in her capacity as an editor, finally seeing Mitchell’s artwork is a wonderful reminder that writers I admire also retreat to the privacy of the studio, producing work that can’t be fully captured in language. When I asked about her feelings on art and writing, she described the two practices as very separate. For her, writing feels more optional, whereas art is a core thing that defines who she is. At the same time, because her artist persona is not a public one, the nature of that work feels more insular.

Since Title’s restructuring in 2016, Mitchell has taken on the even larger role of Managing Editor, which she does alongside her nearly-full-time job as Exhibition Coordinator at the Center for Creative Works, a non-profit art studio for adults with disabilities, her job as a writing tutor at PAFA, and her studio practice. Her generosity and willingness to wear so many hats is inspiring — but in conversation, I got the sense that she is motivated by a real feeling of responsibility to Philadelphia’s community of criticism-readers. She knows that platforms like Title Magazine require consistent upkeep and the donation of personal time to remain viable, even when it is hard.

While Mitchell describes editing as a type of service to the community, Julia Clift emphasizes that writing is ultimately a tool for her own understanding, and that there must be a sense of empathy between her and the work she reviews. And although she considers her writing as her work, her studio practice has to come first. For a year or two, she stopped writing altogether to focus on drawing and painting, and though she has since returned, the desire for more studio time is perpetual. Mitchell tries to schedule one day out of the week for her studio – but ultimately produces much of her work at residencies, where she can fully devote herself to making art.

Both Clift and Mitchell question the long-term sustainability of playing so many roles. I too sometimes find myself questioning the value of writing when I would rather be painting. In a community where most writers are also artists, perhaps this is why it’s difficult for publications to hold on to regular, monthly contributors. Yet, Julia Clift and Samantha Mitchell demonstrate that while criticism can arise from a personal desire to write, it is ultimately a service to artists and readers. A piece of critical writing can validate someone’s career or hold their audience accountable. In the absence of a contemporary arts economy sustained by collectors and gallerists, artists must step up to fill myriad roles — critic, curator, collector, viewer. Perhaps this artist-run ecosystem of Philadelphia is unsustainable, but it is also a small utopia, built on feats of DIY acrobatics and the generosity of time and labor.