The blockbuster exhibition Chuck Close Photographs, currently on view at the museum of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), offers the first comprehensive look at the artist’s expansive oeuvre of image and print-based work. With around 90 prints in the show, it’s a massive display of work, and sometimes enjoyable with poetic and evocative pieces but many works which lack the ability to inspire.

Painter of portraits who relies on photography

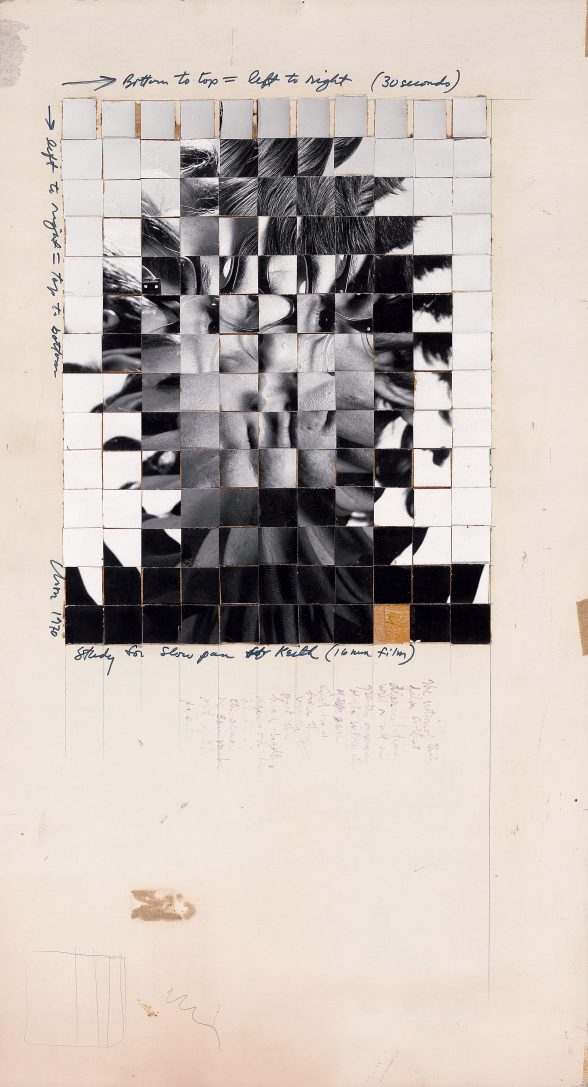

Close is well known and well respected for his painted portraits of friends in the art world, made in a semi-abstract style in which thousands of tiny colored lozenge shapes in graph-like squares come together to make one cohesive overall image. His paintings and prints reside in permanent collections all over the world, and his portraiture and self-portraiture need no introduction as landmarks of photorealism and contemporary art. What is lesser known is that many of these portraits were realized from photographic maquettes – a method of “sketching” that eventually grew into a major component of Close’s work independent of the canvas.

The organizers of this exhibition guide viewers through the artist’s use of photography as a tool to his realization that a photograph in and of itself could be an “end product,” a notion that was hardly new by the time Chuck Close embraced it in his own work.

Technical execution of photos is spot on

The artist’s photographs are well taken, I can’t argue with that. His knowledge and execution of many alternative and labor-intensive processes is spot on, from delicate daguerreotype studies to the massive, multi-panel Polaroid nudes that have gained him the most recognition of the bunch. I’m grateful that artists like Close have mastered and helped to keep these techniques alive. But, put aside the processes, and what I feel about the work is…apathy.

Celebrity photos well done but subjects not relatable

The most innovative or captivating aspects of Close’s photographs come down to medium. The 20” x 24” Polaroid works in particular are stunningly executed, with a clarity and seductive tonality that makes some faces so real they feel like they’re about to start speaking to you. What the portraits lack is the ability to elicit empathy or a strong connection with the viewer, which is mostly due to his choice of subjects – friends and celebrities like Bill and Hillary Clinton, Brad Pitt, and Jasper Johns. These celebrities are just not really relatable, and Close’s depictions do nothing to humanize people who are already monumentalized as heroes or demons in the media.

Even if the point of his portraits isn’t to highlight the individual, but rather to establish a more formal array of studies of the human form divorced from personality, the presence of so many notable personalities makes that difficult as well, and I feel the same way when he turns the camera on himself.

The Polaroids and the many taped-together and drawn-on photographic maquettes for paintings are all interesting as views into the artist’s process and the realization of his final works. The exhibition text doesn’t shy away from discussing how his photography relates to his painting, going into great detail about the way in which Close graphs out his photographs so that he can more easily paint massive works square by square. I think it a shame that there wasn’t at least one painting on the walls to visually demonstrate the progression from photo to painting. The presence of a painting would have made the show stronger by offering context to the photos.

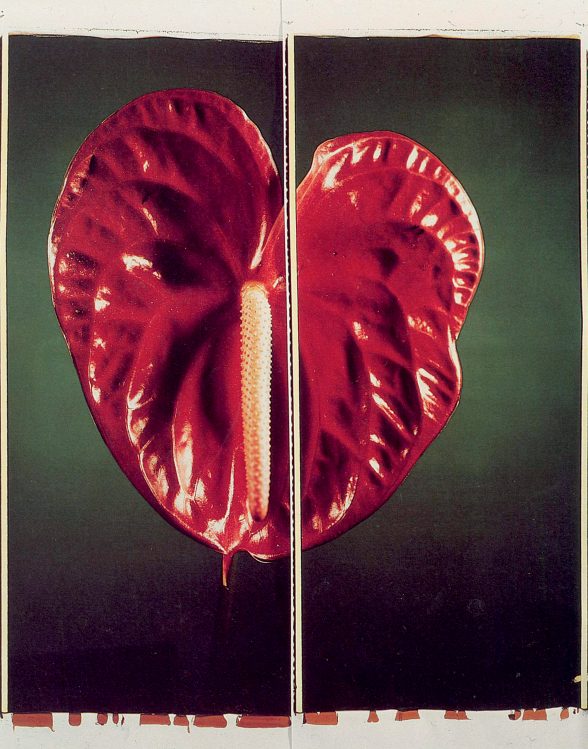

Flower photos a respite from celebrity portraits

A bright spot in the show, giving both beauty and a rest from the weight of the celebrity photos — is the floral studies. The large, two panel 102” x 83 ¾” color prints are seductive “bee’s eye views” of anthurium and chrysanthemum that are easy to get lost in, especially at such a large scale. The colors are silky and rich, the clarity and definition of petals receding into richly colored backdrops, the flowers seem to have personalities of their own.

Equally detailed as the flower studies but less poetic, the monumental multi-panel nudes, seem cool and pseudo-classical studies of form rather than interpretations of personality. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it does stunt the effect on the viewer (besides their stunning technique).

The idea that a portrait of a flower can be more sensual than a study of a monumental nude isn’t new. Georgia O’Keefe built an entire career and etched herself into the pages of art history with her flower paintings, which are widely viewed as symbols of the female body despite her lifelong denial that her paintings were “in any way sexual.” Robert Mapplethorpe’s sensual images of flora are one stunning photographic precursor, and Nobuyoshi Araki’s translations of explicit eroticism into flower still-lives in the mid-late 1990’s are a later example. Close’s flowers are between the hyper-real and erotic, and overpower their neighbors on the wall.

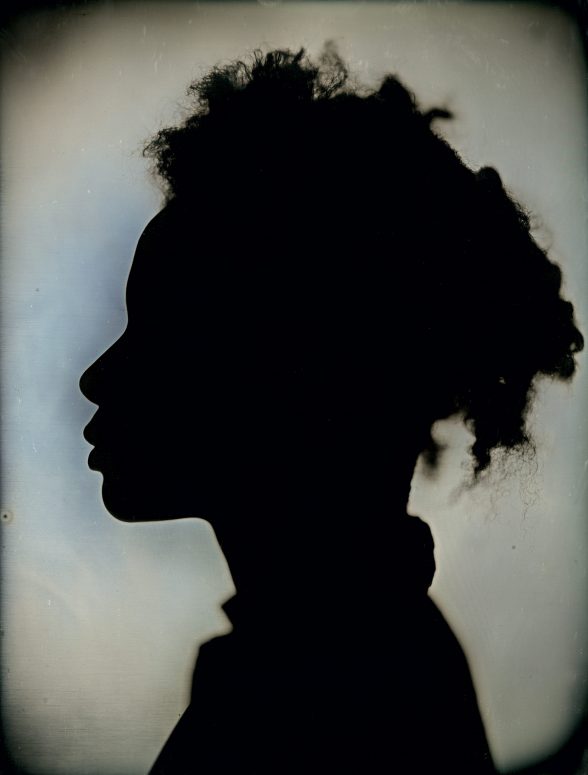

Another highlight is his portrait of Kara Walker, in the form of a daguerreotype and print on paper. Close hints at the style of her own work here, as her mostly silhouetted form is illuminated just enough on the edges to reveal the details of her face. It’s executed to perfection in both print and photograph.

Chuck Close Photographs is an exhibition of contrasts; I oscillate between boredom and fascination with the work. This is a case of appreciating the larger context and influence of an artist’s work and yet finding their individual works underwhelming.

Chuck Close Photographs is on view at the Fisher Brooks Gallery, Samuel M.V. Hamilton Building at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts until April 8, 2018.