“Black Atlas,” an exhibition at the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College through March 9, 2018, grew out of a residency that the artist, Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn, had at the Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm in 2015. According to the artist, “the museum made it clear that they were looking for someone who either had a history of migration in their family history or was part of a diasporic community,” which was an indication that they were inviting a postcolonial critique of the museum’s history and collections.

Artist’s residency at museum spawns post-colonial critique

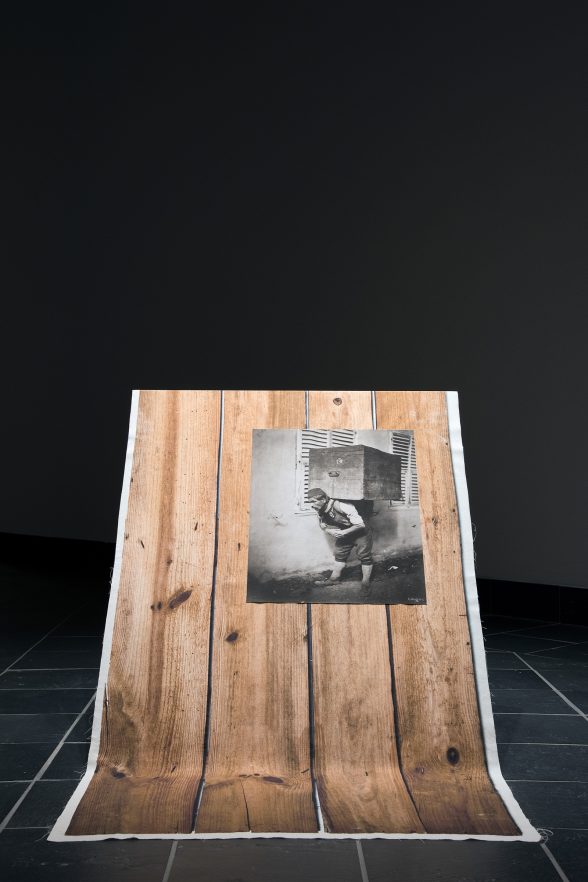

Nguyễn became interested in photographs she found in the museum’s archives. One recorded the portable darkroom which enabled one of the ethnographers, Erik von Otter, to develop photographs in the field during his work in Kenya. In one photo, Von Otter is in the foreground, crouching next to his equipment, with a group of indigenous porters behind.

Nguyen was interested in the division of labor, with the Kenyans used to transport equipment and artifacts, while the European interpreted the material. She was also intrigued to learn about the role of photography in asserting the dominance of European culture.

Background of museums, purpose of displays, and other artists’ critiques of ethnographic collections

Almost all objects in art, archaeology and ethnography museums are out of their native habitats, and with ethnography collections that is certainly the point: to show the material artifacts of foreign cultures as a way of better understanding the peoples. The field of ethnography was formed during the period of colonization and reflected the same ideas about the superiority of European culture. By now any educated person should be aware of the fallacy of a hierarchy of human cultures and be wary of research based upon that assumption. Another problem inherent to the field is that of the outsider in interpreting another culture. Not only is misinterpretation likely, but there is also the possibility that the indigenous community is creating a story especially for the ethnographer, or making jokes at their expense. Juan Downey‘s pseudo-ethnographic videos from the 1960s and 1970s raise these questions.

I assume Nguyễn’s emphasis upon the transport of ethnographic material en route to Europe was based upon the photographs she discovered in the museum’s archives. She also uses period photographs of the museum storeroom and the scholars’ offices and full-scale images of old packing crates. Earlier critiques of ethnographic collections focused on the means of their acquisition – by theft, coercion, or sale between parties with unequal knowledge. Indigenous peoples have criticized the presentation of their cultures as fixed in the past, rather than evolving. This is addressed by Canadian artist Brian Jungen with his totem poles made out of high-end sports shoes. Other critiques have questioned the ethics of putting the cultures of others on display, such as the performances by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña as “The Couple in a Cage: Two Amerindians Visit the West” (1992-93) where the artists offered themselves, caged, for museum display. Some museums have become self-reflective; for at least thirty years the Field Museum in Chicago has included dates on its display cases to dispel the idea that they are unmediated presentations, rather than interpretations that reflect the ideas of specific periods.

Exhibition introduces visitors to critique of collections

“Black Atlas” will be valuable if visitors are made to question their assumptions about ethnographic collections. For those already aware of the discussions around this material, it is hard to see what Nguyễn’s project contributes to the discussion.