It is difficult to make art about identity without self-indulgence, to speak about being marginalized without falling into sentimentality, or to address the personal without fetishizing pain. It is difficult but deeply necessary to avoid simplicity for the sake of being consumable, even if by the most well-meaning of audiences.

Punctual Reality is the second iteration of a previous show entitled Imperfect Tools for Navigation, and like its predecessor, it proposes ‘imperfect’ solutions to these problems. Much of the work in Punctual Reality utilizes a classic bait-and-switch mechanism. James Bouché, Jared Rush Jackson, and Devin N. Morris lure the viewer in with a cool, slick pop-culture veneer before tackling underlying subjects of personal significance.

With the exception of Jackson’s Carp 163 (a loosely-figurative painting of a fish) and Morris’s Build a Pool (a lovely painted-paper collage of two blue cartoon-like figures crying a sea, while glossy magazine cars bob in the waves), few works bear evidence of the artist’s hand. Be it through laser cutting and fabrication, the mechanics of screen capture and vinyl lettering, or the sheen of fashion photography, all three artists consciously co-opt the techniques of mass-production.

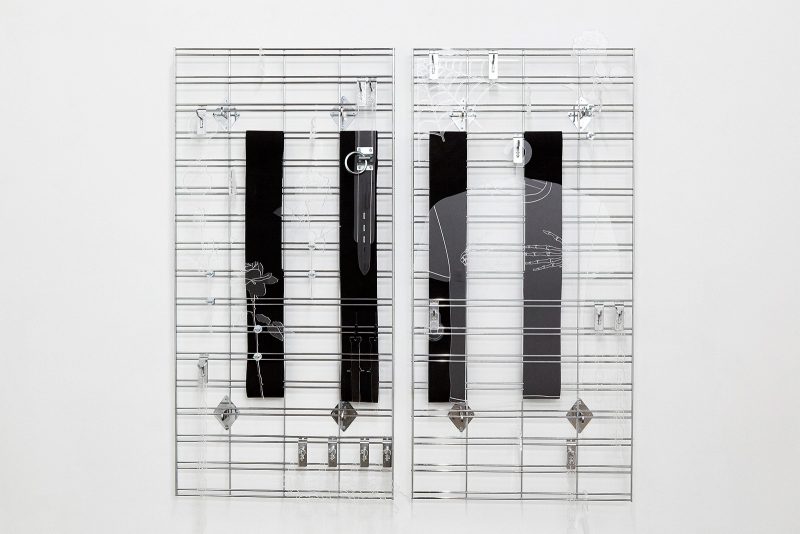

Collectively titled They Sewed Fig Leaves Together, James Bouche’s sculptures are full of musings on masculinity, Mormonism, and consumerism. Clear, laser-cut acrylic daggers, fig leaves, roses, skeleton hands and t-shirts with heavy-metal logos hang on sleek chrome merchandise racks, affixed by black zip ties and polyester straps. Flags are to nations as these icons are to subcultures, and together, they’re the ghostly artifacts of an individual — but whom? The whole installation feels a bit S&M, but do they go to Hot Topic or the Renaissance Faire? The dagger suggests high fantasy, which I personally love, but which has its own dark underbelly (take the dedicated Lord of the Rings forum on white nationalist site, Stormfront, where klansmen debate whether the series is really about people of color invading Europe, and if Eowyn is a “feminazi”). Is this sculpture a portrait of a basement-dwelling “meninist,” or is this the bassist of a band I like? Or is it me in the eighth grade? The generic cutouts provide no answer, but any discomfort is ultimately countered by the absurdity and humor of Bouche’s tableaux — there’s no danger in a fake knife.

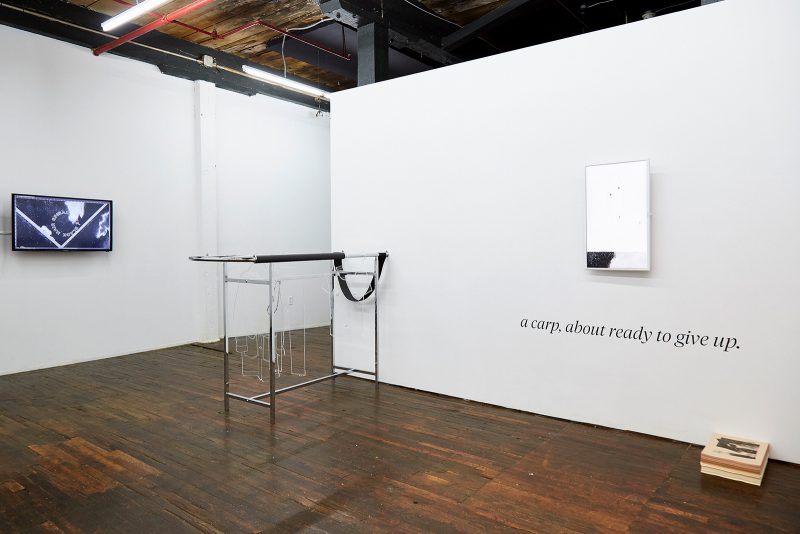

Jared Rush Jackson addresses the experience of blackness through layers of metaphor and obfuscation. In a carp, about ready to give up, Jackson displays vinyl text and risograph prints with a video of a vectorized circle being yanked to and fro by a fish-hook cursor. The text comes from a book about fishing, and Jackson notes the similarities between the language of fishing culture and the way black bodies have been treated throughout American history — white men, holding the limp bodies of their catches aloft for the camera, the size of their prey in proportion to their proof of virility. Although the ultimate and obvious end of this comparison is the history of lynching, Jackson’s work never spells it out — his work consciously refuses to illustrate black pain. The video’s impersonal and hypnotic looping holds attention just long enough to nudge the viewer toward metaphorical possibilities.

The fashion magazine page is a funny and contradictory confluence of forces; it sells things that are expensive on pages that are printed as cheaply as possible. It is a vehicle for disseminating assumptions about value. By using the medium of fashion photography to portray queer black men in his local communities of Baltimore and Brooklyn, Devin N. Morris casts these individuals in positions of power. The glossy prints all belong to a series called In a Dignified Fashion. Here, figures are staged in backyards, using swaths of colorful fabric as backdrop, utilitarian clothing, and prop. Morris’s use of fashion aesthetics casts these individuals and their lifestyles as beautiful and enviable. The photographs are hung in an installation of wallpaper-like cloth strips and painted furniture — a macro universe of his collage’s intimate narrative. By using both painted paper and bits of magazine imagery to articulate a psychological space, Morris’ work insists upon the possibility of communicating something raw and personal through the mass-cultural imagery all around us. It’s a utopian, optimistic use for collage.

Bouché, Jackson, and Morris engage with very different identities, but all three share a desire to tackle the topic abstractly, diluting universal themes from personal experience. Identity has become such a frequent and expected topic of discussion, that we begin to look at artworks about race and gender with a quickness unconducive to nuance or criticality. In this context, Punctual Reality asks us to consider: what does an art of identity politics look like that encourages slow reading, that is subversive precisely because it does not illustrate identity or pain?

High Tide is an artist-run gallery and project space located in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia. Their group exhibition, Punctual Reality is on view through March 17.