When it comes to how art is displayed in relation to its venue, few arrangements delight me more than when historic sites self-reflexively host contemporary art that comments on or critiques some aspect of the venue itself.

Installation as critique

I first began to think about the potential of exploring clashing — and complementary — relationships between venue and artwork when I saw the 2016 St. Leopold Peace Prize competition at Austria’s Stift Klosterneuberg (shtift kloh-stur-noy-burg) monastery. Each year this competition invites contemporary artists to submit work in response to a specific Biblical theme, to be displayed in the monastery, with a prize going to the work that best addresses contemporary humanitarian or social issues. In 2016, the prompt was “The Power of Greed,” which provided ample intertwined visual and thematic interest against the backdrop of a massively ornate and centuries-old gilded church interior. It cannot have escaped the organizers of the exhibition that merely hosting art about “The Power of Greed” (whether that greed manifests in the destruction of the environment or the enslavement of human beings for profit) in a Catholic church would read as institutional self-critique — a critique outlined by none other than Pope Francis.

Victoriana Reimagined, the new intervention at Germantown’s Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion, is another example of how contemporary art in a decidedly non-contemporary space can not only delight the eye, but also encourage the viewer to think more deeply and critically about the relationship between past and present. The three artists featured in Victoriana Reimagined — metalsmith and jeweller Melanie Bilenker, painter and sculptor Jacintha Clark, and installation/paper-craft specialist Talia Greene — each chose an aspect of the elegant nineteenth-century house as inspiration for their own work. In turn, each of their works draws attention to, and aims to pull apart, many of the myths surrounding the Victorian era as we understand it, drawing connections between the Victorian era and our own contemporary moment.

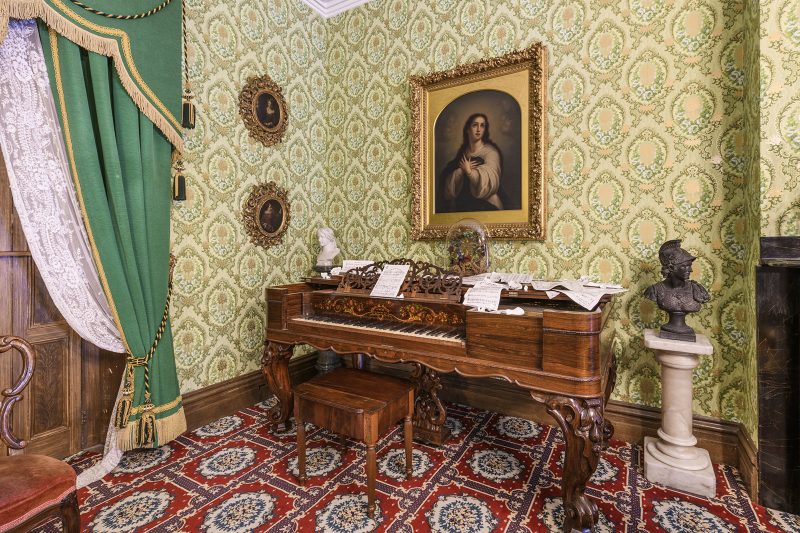

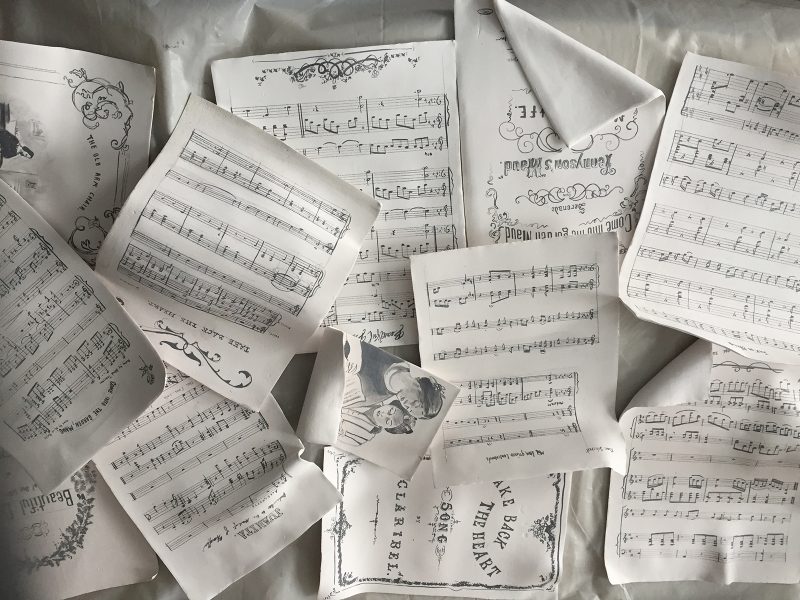

Greene’s installation, located in the dining room, envelops the famous Maxwell Mansion chandelier in a bevy of gold-painted paper grape leaves and foxes that trail down and rest on the table alongside the Parisian china and elaborate silverware. That the design of the chandelier was inspired by Aesop’s fable of the fox and the grapes, provides the perfect opportunity for Greene (and contributing sound artist Jordan Deals) to draw attention to the indulgence of the idle rich during the Victorian era. Combined with the ambient sounds of dinner table chatter and clinking glasses, tinged with the cawing of birds, Greene’s handiwork creates a sense of over-ripeness, of life just about to decay. While the poor worked endless shifts at power looms or polluted their lungs mining the coal that powered great trains across countries, the wealthy sat at tables like this one, delighting in the fruits of their labor — fruits that, under Greene’s manipulation, symbolically cascade down towards the table, hanging like a thick, potent cloud in the center of the dinner conversation, now impossible to ignore. Moving into the parlor, we encounter Jacintha Clark’s deconstruction of the Victorian façade of well-ordered propriety that, for many of us, represents the sum total of our knowledge about that era. Taking the mansion’s grand piano as both setting and jumping-off point, Clark has created porcelain versions of Victorian-era sheet music and strewn them messily about. It is as if we have just stumbled upon this piano at a moment of repose while the family to whom it belongs takes a break from pawing through their sheet music, the keys still cooling down from the touch of fingers. Clark’s deliberate orchestration of clutter highlights one way that the family who lived in this house is as recognizable, as raucous and lively, as any family living today. Across the entry hall, Greene shows us the Victorian elite delighting in excess; Clark reminds us that they were also very real people who enjoyed belting out renditions of songs like “Come into the Garden, Maud,” based on Tennyson’s poem (and recreated in porcelain on the piano’s lid). Even viewers without pianos in their homes can relate to the sense of casual joy in crumpled sheet music, of participating and interacting with loved ones. According to Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion director, Diane Richardson, it was important that the artists in this show be women. As women in the Victorian era were famously confined to the domestic sphere, how better to undermine the very conceit of gendered spheres than by inviting female working artists to actively create and change spaces that would have held them captive a little over a century ago? Melanie Bilenker’s contribution, located upstairs in the mansion’s master bedroom, draws upon the Victorian traditions of hair art and tunnel books to recreate (in miniature) her own bedroom-slash-work space. The craft of Bilenker’s composition must be seen to be believed; incredibly, all of the lines that render the scene are actually carefully-arranged strands of hair. Bilenker rejuvenates these now-antiquated crafts to create a portrait of a kind of female liberation, recasting the bedroom as an environment that encompasses both Victorian spheres. Even as she places her work in the stifling atmosphere of a Victorian bedroom, she reminds us of the strides towards and within the public sphere that women are still making today. When a work of art sticks out of its setting like a sore thumb, it invites us to reconsider the very fabric of that setting, illuminating long-hidden cracks in perfect façades, or, in the case of Victoriana Reimagined, opening up gaps in how we’ve thought about history. Greene, Clark, and Bilenker each use a different part of the Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion to explore the complexities of labor, familial relationships, and gender, showing us that the Victorian era was as messy and fraught as our own times, and that perhaps, in many ways, the past is not a remote relic, but a lingering presence even today. Tours of Victoriana Reimagined and the Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion are offered on Saturdays at 12:15, 1:15, 2:15 and 3:15 p.m. Individuals living in the 19144 zip code may view the exhibition free of charge.

Gender and confinement