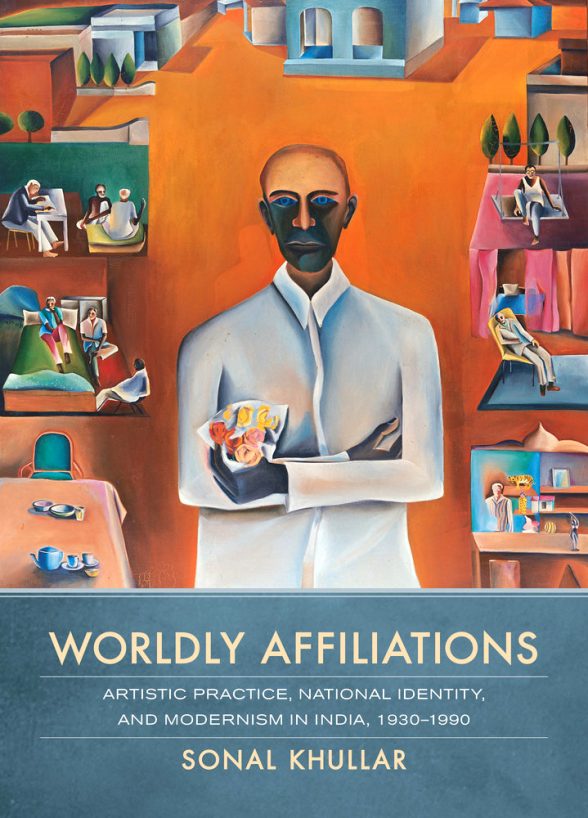

Sonal Khullar, Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity, and Modernism in India, 1930-1990, Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.

Worldly Affiliations opens with work by contemporary artists: Zarina, Dayanita Singh, Nikhil Chopra, and others who have increasingly appeared in international exhibitions, art fairs and Western museums over the past twenty or so years. In response to the assumption of a global contemporaneity where, thanks to the internet, everyone reads “Artforum” — and “Artforum” increasingly covers work produced and shown throughout previously-ignored continents — Khullar emphasizes that Indian artists come from a locale with its own, complex history which is unlikely to be readily transparent to outsiders. She charts a modernist approach in Indian art from the 1930s to the 90s, in contrast to previous scholars who posited a colonial tradition which made a clean break in 1947, with Independence, after which India developed a modern movement.

Discussions of modernism beyond the West are fraught with disagreement over its nature and its relationship to the Western tradition that has dominated art history and criticism. Khullar’s modernism involves a negotiation between Western and Indian values. She describes “a system of transnational exchange and critique” that “refutes the idea that artists in India produced either modern art without modernism – disidentification with artistic practices in the West – or modernism marginally modified – Western norms re-purposed for non-Western contexts.” Her book is fully informed by scholarship on Orientalism, primitivism, nationalism and post-colonial studies, but is written with a clarity that makes it suitable for non-academic readers.

Khullar focuses on the careers of four painters, using them as case studies: Amrita Sher-Gil (1913-1941), Maqbool Fida Husain (1915-2011), K.G. Subramanyan (1924-2016) and Bhupen Khakhar (1934-2003). She situates them within a broad view of India’s art culture which includes institutions of art education and exhibition, critical discussion and writing, artists’ communities, interactions with Western art and artists (both in India and through travel abroad), and ongoing arguments about the appropriate artistic expression of a newly post-colonial state. The book is profusely illustrated, with numerous color plates – unusual, for a university press publication. This is crucial for artwork to which most readers will likely have little or no first-hand exposure. This volume is an important contribution to the study of Indian modernism and to the broader topic of modernism beyond the West.

Understanding Indian modernism

I am still struggling to understand Indian modernism, and must admit that I sometimes found it hard to see what Khullar describes. This is not a criticism; rather it acknowledges her assertion that Indian art has a history that is little-understood elsewhere. One problem is that I know most of the artworks only through reproduction – and the lack of dimensions in the captions for Khullar’s study makes it difficult to envision unknown works which range in scale from miniatures to murals. But beyond that, I am ever more tentative about my ability to gain an insider’s understanding. Three examples: despite the discussion of Sher-Gil’s incorporation of Western modernism with Indian subjects and artistic traditions, when I look at her paintings (and I actually saw two at Documenta 14), I am reminded of 1930s American regionalism — with a simplified representational style and a cosmopolitan artist’s romanticism of rural life.

A second point concerns the Indian understanding of Western modernism. By all accounts the two European artists who made the most impact were Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee. Klee’s work was exhibited in India and his writing, in English translation, was influential; but no European or American artist would be likely to give him that prominence. This is an instance where local artistic traditions and aesthetics probably gave Klee’s work a special meaning — something I would like to know more about.

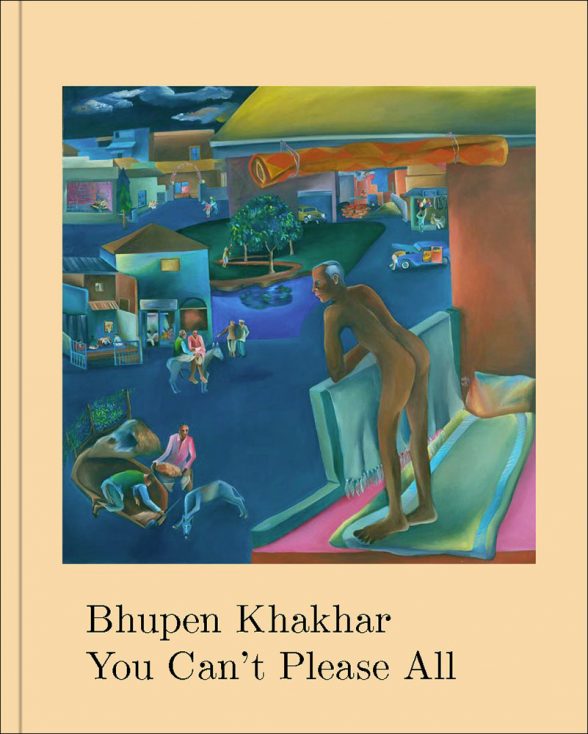

Finally, I was baffled when Khullar described the palette of a painting by Bhupen Khakhar, “You Can’t Please All” as “muted” (see the cover illustration of the catalog below). This is startlingly-divergent from the description I would give of a painting in saturated blues and greens whose right third is largely marigold orange and shocking-pink— colors also used as highlights throughout the rest of the composition.

I would love to read another study that discusses precisely the points of friction in our traditions, something which Khullar certainly has the background and skill to write.

Chris Dercon and Nada Raza, eds. Bhupen Khakhar: You can’t please all, London; Seattle: Tate Publishing; University of Washington Press, 2016

(U of Washington Press Amazon)

This fully-illustrated exhibition catalog is an introduction to an artist whose work is almost completely unknown in the U.S., yet would likely find an enthusiastic following; Khullar reproduces one of his paintings on the cover of her book. The Baroda (Gujarat)-based Bhupen Khakhar created a figurative and sometimes narrative art which drew upon a variety of sources including Kalighat paintings, Indian miniatures, commercial devotional paintings, Tibetan mandalas, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s “Allegory of Good Government,” the paintings of Pieter Bruegel, and the commercial packaging of Indian domestic products. Khakhar was deeply involved with other painters, poets and writers, but his work stands out for its urban subject matter and frank view of homosexual desire and social activity.

The catalog includes contributions from numerous artists and colleagues who knew the artist as well as analytic texts, a chronology, and a reproduction of an early publication by Khakhar that reveals his self-fashioning.

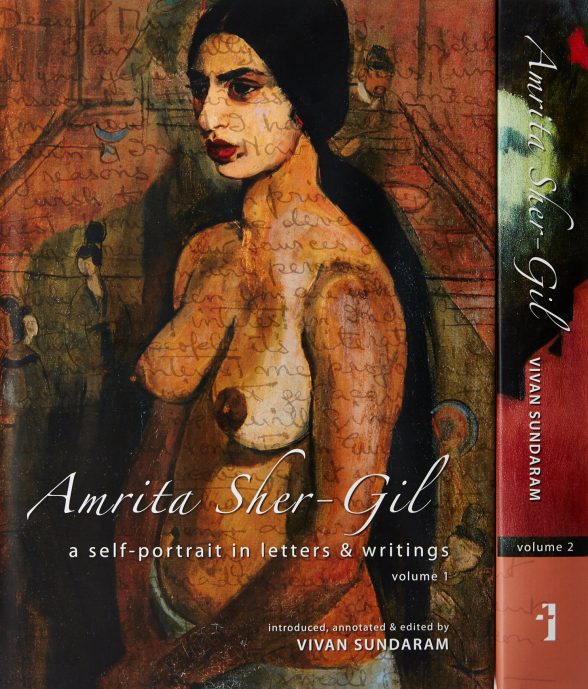

Yashodhara Dalmia, ed. Amrita Sher-Gil: Art and life, A Reader, New Delhi; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014

(Oxford University Press Amazon)

Amrita Sher-Gil holds a prominent place within twentieth century Indian art, and her biography — a Hungarian mother and Sikh father, Parisian education, she was a beauty who died at 28 — is the stuff of a Hollywood biopic. This volume includes a short statement by the artist and critical writings on her work that were published from 1942-2009, giving a picture of her evolving reputation. It is illustrated throughout with black and white photographs and illustrations of her work, and a dozen color plates — none of which give their size, so that readers gain a limited visual idea of her oeuvre. Still, it is extremely valuable as an addition to the limited literature readily available in libraries beyond India.