I have never forgotten a small work by Howardena Pindell that I first saw in the late 1970s at AIR Gallery in New York; I was thoroughly seduced by its beauty, which was bound up in its form; it demanded intense viewing at close range. The artist had developed her own technique. Using a hole-punch she generated tiny, paper dots which she scattered in abundance across a support of board; they did not lie flat but were orientated in all possible directions, creating a three-dimensional zone of activity in front of the ground. Their arrangement suggested movement and chance — and I could imagine further movement re-arranging them and some of them settling down. A group of her punched paper works have numbers inscribed on the tiny dots; for others the dots are colored and organized with a grid constructed of fine thread. Some are dusted with powder, giving them a more complex, atmospheric quality.

A wakeup call

The impact of Pindell’s video, “Free, White, and 21” (1980) is equally fixed in my memory. Her stories of white women dismissing the racism she faced as a black woman — told in a deadpan voice, with the artist alternately appearing as herself, then in whiteface — was a slap in the face, a wake-up call. Pindell, who has an MFA from Yale and worked at the Museum of Modern Art for twelve years, demonstrated that even an artworld colleague with an Ivy League degree regularly had faced obstacles that I neither recognized nor understood. She has lectured and written powerfully of her experiences in the overwhelmingly-white art world. She also began documenting the dearth of artists of color in mainstream galleries and museums at about the time the Guerilla Girls were highlighting the absence of women in these spaces. Her lectures and writings have been anthologized and, along with “Free, White and 21,” they have offended a number of people who would rather not confront the subject.

“Howardena Pindell: What Remains to be Seen” grants the artist the attention she has long deserved and will be a revelation to many viewers who are unlikely to have seen a large body of her work. It was organized by Naomi Beckwith of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago and Valerie Cassel Oliver of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where it will be on view August 25 – November, 2018. It will also travel to the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University from January 24 to June 16, 2019. Once again all of the major museums in New York — as well as those in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles — have missed out. This is an important exhibition by a remarkable artist with a long and distinguished career.

Before and after

The exhibition’s installation in Chicago was absolutely gorgeous. It filled the entirety of the MCA’s high-ceilinged galleries and demonstrated the visual beauty and artistic breadth of Pindell’s achievement. The exhibition was bifurcated, as the artist’s life has been; in the Northern galleries her drawings, collages and acrylics on canvas from 1968-1979 use the language of abstraction. In addition to numerous small-scaled drawings and collages on board were three very large paintings in luscious colors, created from layers of dot patterns that have a family resemblance to the hole-punched works.

The galleries in the museum’s South wing exhibited work done following an automobile accident that left Pindell with amnesia. She employs various degrees of figuration – initially as a means of recovering her memory and her life – although they explore her position as a black woman in still racist America more than her individual experiences. She sometimes embeds figurative elements within larger fields so they read abstractly at a distance, and occasionally returns to pure abstraction. This work directly addresses racism, war, hunger and other topics of social justice, as well as her travels abroad; the most recent work reflects the artist’s interest in astronomy.

On handwork and labor

Describing Pindell’s work as two separate modes implies a sharper division than the artwork manifests. Not only is her personal aesthetic and remarkable ability as a colorist visible throughout both bodies of work, but all of it is characterized by an insistence on the handwork involved. Pindell’s art involves accretions of parts that have been arduously assembled through a process of almost obsessive focus and labor. It is clear that her work is the product of long, very slow activity, which inherently raises the question of time – the time required to produce a painting, the time of a life – hers or ours – and what an individual can accomplish in that time. Pindell’s moral urgency and sense of responsibility to mankind and our planet are the basis of every hole punched, every brushstroke, every number inscribed in pen.

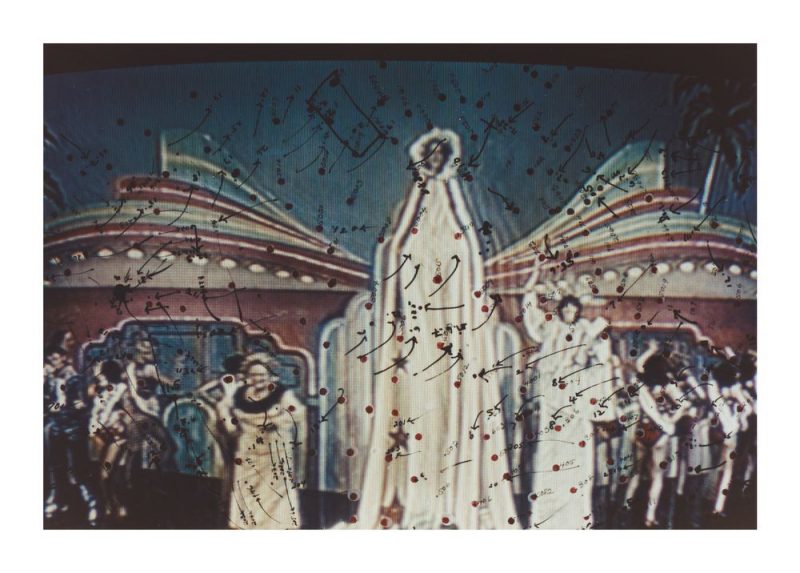

In the middle of the exhibition were a group of works that toggle between figuration and abstraction. With these “video drawings” Pindell once again invented her own technique: she drew arrows, numbers and dots on clear acetate which she fastened to her television’s picture tube, then photographed the televised image overlaid with her marks. The markings, which appear to be scientific studies, do not relate to the tv imagery in a systematic way, and yield no data. The fact that many of the video drawings record athletes certainly evokes sports statistics as well as the various physiological studies meant to maximize athletes’ performance. Pindell’s video drawings speak to the quantification of knowledge, our search for meaning through various analytic forms, and our attempt to create order within the inevitable, fortuitous aspects of our lives. The poor resolution from the cathode tube images resembles pixelated digital imagery and gives further emphasis to the mediated way we receive much of our information. They are criticism of the algorithm before the algorithm determined so much of our world.

“Howardena Pindell: What Remains to be Seen” was on view at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art from February 24 – May 20, 2018.