Agnes Martin is something of an artist’s artist. This Canadian immigrant to the US who taught art before deciding at age 30 to become an artist, this nomadic denizen of New Mexico and downtown Manhattan, this minimalist, this Buddhist, this painter of the self, this schizophrenic, this mystery, this believer in art, this fabulous success, this homesteading hermit, made work as rarefied and idiosyncratic as she was. Although its installation inhibits an optimal experience of her meditative work, Agnes Martin: The Untroubled Mind at the Philadelphia Museum of Art provides an opportunity to see more Martin in one place than has been possible in Philadelphia since 1973.

The eye of the beholder

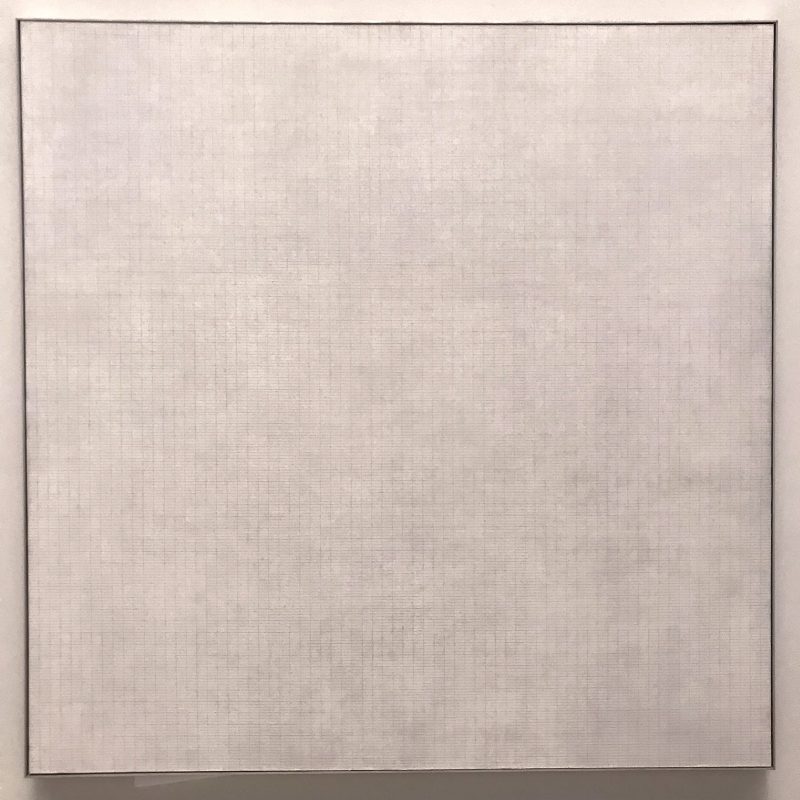

Agnes Martin’s art is a matter of pure perception. The power of her iconic grid paintings, created in the 1960s and 70s, originates in the precision (and imprecision) of the act of their creation, in the specific and idiosyncratic play of form, material, scale, and the uncommon humility of Martin’s own making hand. And her exquisite work is realized as we, her audience, experience that play in the movements of our own organs of sensation and feeling. Part of the art lies in making the object, but an equal measure lies in seeing it.

Consider Leaf (1965), the most assertively engaging of the five large paintings currently on view. Its coarsely gessoed, white, six-foot square surface is penciled all over with a network of slender, ruled gridlines. All of the verticals and every fourth horizontal line are subtly darker, making patterns of dark, near-perfect squares discernible, each one composed of four stacked, slender rectangles. The way Martin applies the discipline of the grid onto the irregularity of the color creates a sense of rhythm and movement. Some of the thousands of rectangles in the grid seem lighter, some darker. Occasionally, particularly at the edges, the graphite seems to hunker down into the wash, almost vanishing.

Because the surface is large and its effects are varied, an up-close look at Leaf is a comedy of the mind chasing after and never catching its natural hunger for perception; one section seems to float a bit; a patch of grid on the periphery of my vision seems in sharper focus. I step back, to take it all in. With distance, particular irregularities become invisible, but a softness of surface persists. Another step back and the whole grid disappears into a cloudy mist.

Pure perception

Martin’s Leaf—like all of her work—proposes a universe in which everything matters. The heaviness of one line, the way it trails off as it gutters into the periphery; the way it tracks the weave of the canvas and then doesn’t; the bristle of the canvas when a nub protrudes, enveloped by paint and encompassed into the art, still it gives the piece a near-microscopic third dimension, saving the grid from mere abstraction, making it real. The process of coming into that world, and coming to know it, is a process of coming to know ourselves—not our thinking selves but the seething, craving, knowing of our un-intellectual perceiving spirits—along with the “thoughtful” obstacles that our minds throw up to screen against our pure perceiving.

Leaf is not so much a painted image as it is an event. An encounter that tracks the nuances of the process of perceiving it takes time and a steady, gentle focus. And there’s a second wave to the event, which is the unbidden and unexpected shimmer of feelings that arise in response to the painting’s provocation. As the flutter and flit of my searching awareness rustles and resolves into a floating expansiveness, I am charmed, energized by its racing power, then soaringly amazed and at last, calmly, though provisionally, settled, as I sometimes feel on a hike through endless mountains.

It is, however, not so easy to sustain such a reverie in looking at this show. It’s hung in a hallway, beneath the looming barrel of Sol Lewitt’s electric-blue abstracted sky and with the audio of a nearby installation providing a persistent and distracting soundscore. The traffic, the noise, even the proliferation of supporting statements, texts, cards, poems, and take-home posters all mitigate against the close, quiet spectating this work requires.

Obstructed views

Agnes Martin’s work, and this small selection of fine examples of it, deserves to be seen to better advantage. In addition to the four large paintings recently received from the estate of Daniel Dietrich II, the show features The Rose (1965), acquired in 1976, and a number of smaller works. Among these are The Wave, made for a show of artists’ toys at Betty Parsons, and an uncharacteristically sumptuous untitled watercolor grid in blue and brown (from 1963) that is, alas, hung under glass beneath the electric light, so that it’s impossible to see the work without staring down a shadowy reflection of yourself. These curatorial missteps (and there are more—why claim online that her 1973 ICA show “re-launched Martin’s career after a ten year hiatus,” when there’s work hanging in this show from 1967 and she showed actively through 1966? Why write on the gallery wall that Martin “drew from” Minimalism when she was one of its inventors?) are more than unfortunate — they are unjust.

In galleries neighboring the hall where this show is hung, the work of several of Martin’s male contemporaries, including Ellsworth Kelly and Jasper Johns (Martin’s actual neighbors in the early days of downtown Manhattan loft-living) are displayed to excellent effect in one-man rooms, and have been for quite some time. The Dietrich bequest is important because it gives the museum the capacity to help us to see the work of a vital 20th century artist. As slapdash as this show is and as hard as it is to have a pure sensory experience of the majesty of Agnes Martin in it, let’s hope that with The Untroubled Mind the PMA is committing itself to giving Martin—and other female artists—a fuller and better share of its walls.

Agnes Martin: The Untroubled Mind/ Works from the Daniel W. Dietrich II Collection is on view May 19 – October 14, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Mark Lord is a theater director, dramaturg, and writer. A Professor of the Arts at Bryn Mawr College, he also teaches Performance Dramaturgy at the Headlong Performance Institute. He was the director of Big House and Potlatch, companies that produced site-specific plays and performance in Philadelphia. Since 2004, he has been the dramaturg for Headlong.