There’s a tug-of-war between my appreciation for the appearance of ceramic artworks and my desire to rub my hands all over them. Luckily, The Clay Studio National, which consists of submissions from all over the United States, provides plenty to activate both impulses. Take, for example, the dynamic juxtaposition of John Shea’s Plugger and Blanca Guerra-Echeverria’s Embryotic Spur. While Plugger’s craggy, irregular surface glows with the iridescence of light shining on spilled oil, Embryotic Spur consists of a cluster of smaller, more regular forms in muted tones — a pile of smooth, blue pebbles, a single, white, coral-like form, and a looming black egg with the texture of a golf ball.

Putting Place in Perspective

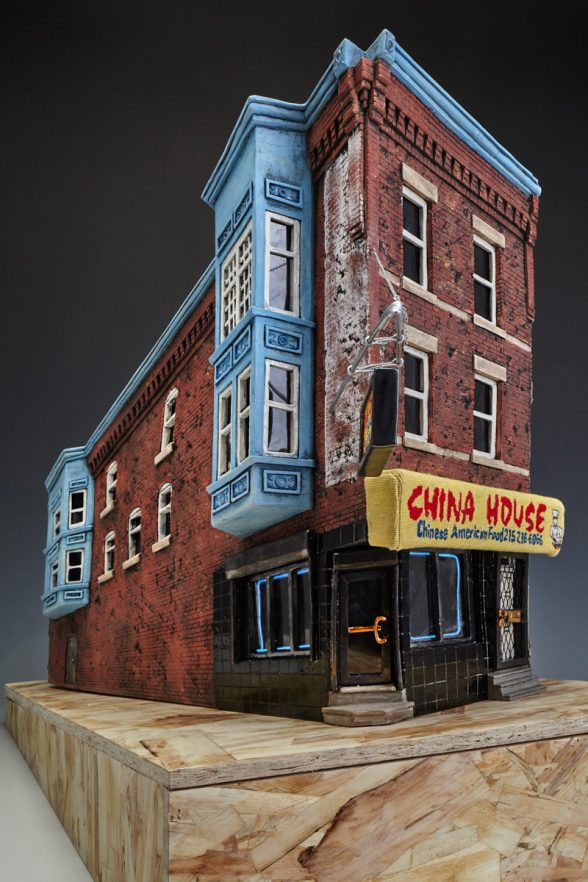

An immediate highlight of the show is Carly Slade’s eye-catching 2046 W Diamond Street, which occupies the center of one of the show’s two dedicated gallery spaces. Using ceramics and mixed media, Slade has constructed a miniature street corner in Philadelphia: an apartment complex with a Chinese restaurant on the street level, all rendered with illusionistic, precise detail. But what makes the work truly dynamic is Slade’s use of forced perspective. As you circle the work, it becomes apparent that Slade has compressed the building on one end and tilted the top of the base at an angle, creating an unsteady feeling that is only exacerbated by the way the plinth (made of what appears to be reclaimed wood) is tilted in precisely the opposite direction. It’s as if the building is mid-backslide and attempting to hold on for dear life.

In Slade’s accompanying text, she mentions that 2046 W Diamond Street is meant to address the “precarious state of the working class,” which it does simply and effectively; the building is the embodiment of those our increasingly unequal society has left behind, lunging forward as if with a last gasp of energy even as the ground tilts away, unsympathetic and unyielding.

A Digital Analog

Another work that caught my eye was Adam Chau’s Txt Series, which is only the second work of art I’ve ever seen to incorporate the smudges left by our fingers on smartphone screens as an integral aspect of its composition. (The first example was Andrea Büttner. Beggars and iPhones at Vienna’s Kunsthalle Karlsplatz, in which the artist used the swiping motions of our daily phone use as an analogue for gestures used in begging.) Chau goes small, creating ceramic facsimiles of iPhones in the middle of texting conversations; the metaphorical residue of the words in the display is indicated by blue smudges over the “keyboard,” where the text message is rendered in epistolary cursive.

Matt Ziemke’s Landscape 10 presents a relative novelty: a ceramic painting mounted to the wall, blurring the lines between two- and three-dimensional work. Kit Davenport’s Conversation is a diorama right out of a children’s book illustration with its pouchy, pillow-like form seated in a chair as the central protagonist. Whimsical and funny, Davenport’s work encourages us to anthropomorphize this already animated form.

Social Commentary in Clay

Hannah Pierce’s Tipsy, Maybe? Unwise Baby uses the literal man-child—a grown male figure sitting in a cradle drinking from a flask—as a point of departure. While the work is technically strong, and while I am sympathetic to its aims—the artist’s text explains that she “[uses] visual metaphors that recognize our dependency on man-made environments and our desperate attempts to conform to living in such unnatural conditions”—it’s not particularly subtle, and indeed, relies too much on the text itself to disseminate its message. Or rather: the message itself is muddle even as the iconography of the man-child is extremely obvious.

Betrayal at Ebenezer, a video by Mary Cale Anderegg Wilson, gets at the political with more grace. In it, the artist drops two hundred unfired clay bowls into Georgia’s Ebenezer Creek, in tribute to the freed slaves who were abandoned by Union soldiers and left to drown in that same body of water in 1864. Although the work is thematically effective, it’s not precisely clear what about ceramic—as a specific medium—made the artist undertake this project.

As it turns out, I am more dazzled by ceramic works that don’t appear to be ceramic, but for viewers who are more object-oriented than I am, there are plenty of more traditionally technical marvels; Laura Kastin’s Dryad, Hitomi Shibata’s Mother, and Takuro Shibata’s Bump all use limited palettes and sinuous forms quite effectively. Ultimately, as with many multi-artist juried shows, the Clay Studio National has something for everyone, from both classic and boundary-pushing uses of the medium to explorations of important societal themes.

The Clay Studio National is on view May 26th – July 15th. For directions, gallery hours or more information about this or other shows, visit The Clay Studio website.