Anderson, Laurie. Laurie Anderson: All the Things I Lost in the Flood: Essays on Pictures, Language and Code. New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018.

(Amazon)

In October of 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded the basement of the New York home shared by multidisciplinary artist and avant-garde darling, Laurie Anderson, and her equally legendary husband Lou Reed, destroying decades of accumulated photographs, performance props, AV equipment and other ephemera in the process. “At first I was devastated,” Anderson recounts in the introduction to her newest book, All The Things I Lost in the Flood, published earlier this year by Rizzoli Electa. “The next day I realized I would never have to clean the basement again.”

Anderson’s openness to and deep curiosity about the double-edged nature of loss is the organizing theme of this volume. Part memoir, part high-gloss coffee table book, part self-curated catalog for an as-yet nonexistent (and perhaps now impossible) retrospective, All the Things I Lost in the Flood chronicles 40-plus years of Anderson’s practice through essays, drawings, performance stills and archival notes. That an object lesson in non-attachment from an artist largely concerned with virtual space and the ephemerality of experience should weigh in at well over 300 pages is just one of many inescapable ironies of this peculiar and ambitious project.

The Many Lives of Laurie Anderson

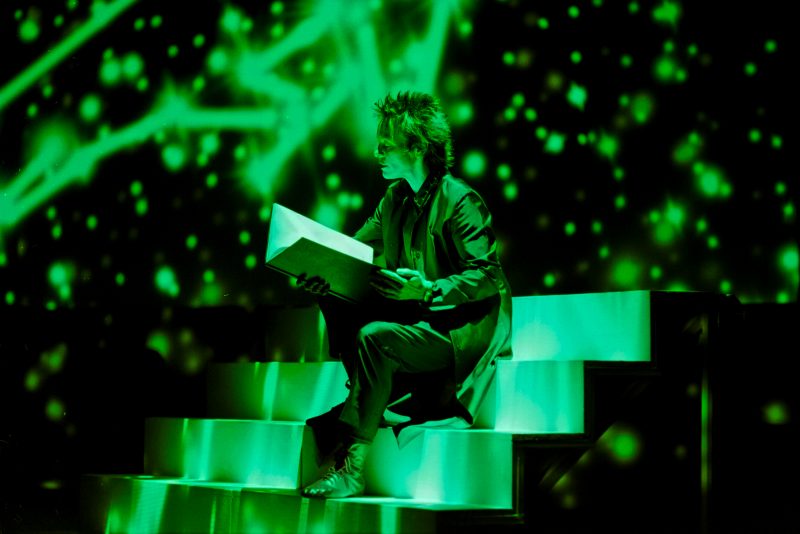

Each of the book’s eight, thematic chapters is a testament to the near impossibility of categorizing Anderson’s rambling career in terms of any single medium or genre. Born and raised outside of Chicago, where she initially trained to be a concert violinist before giving up the bow and rosin to make more time for her beloved pastime of reading, she has worn nearly every art world hat imaginable. From performance art, art criticism and conceptual sculpture in the 1970s, she went on to brief pop-music stardom (and a multi-album distribution deal with Warner Bros) in the 80s before branching out into experimental instrument design, filmmaking, and eventually virtual and augmented reality. All the while she has retained a special relationship to the discipline of drawing, which she describes affectionately here as the “lossiest” medium, and which she uses to particularly poignant effect throughout — transforming photographs from pivotal moments in her life into colored ink sketches that suggest the irregularly-soft focus of memory.

The Language of Loss

In some form, the tension between loss and preservation has always been at the heart of Anderson’s practice, from her earliest performances out of graduate school, playing violin on the streets of New York City with her skate-clad feet encased in a block of melting ice, to her 2015 experimental film “The Heart of a Dog,” which pays tribute to her dearly departed terrier Lolabelle. (See Roberta’s review of the 2015 “The Heart of a Dog.”) Even the deaths of her husband and mother become fodder for her prolific mind. Yet the voice she adopts in the first-person narrative which runs the length of the book, binding its visual materials together, is surprisingly cool and measured. She’s not simply placing laurels on a loved one’s tombstone. This former student of Sol Lewitt, to whom the book is dedicated, is also throwing in her lot with a way of working defined by its near total separation from the world of the average person. The “avant-garde” wouldn’t survive, much less matter if it didn’t produce its own archives and mythologies. And though Anderson’s career has included a dizzying array of increasingly large-scale collaborations at some of the highest profile arts institutions on four continents, old habits die hard. All the Things I Lost in the Flood is as much about staking a claim to ideas which might otherwise be lost to time as it is about letting go.