David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night at the Whitney Museum of American Art through September 30, 2018 is a painful exhibition to view. It is also an important exhibition that is remarkably, sadly current and a must-see for anyone unfamiliar with the depth and breadth of the artist’s work. It is a howl of reproach from the grave by an artist who felt abandoned by his country. He was among the first wave to die of the AIDS epidemic, ignored when not excoriated by fellow Americans. He spoke for the marginalized and powerless and his art was involved in national political debates about AIDS and pornography. Wojnarowicz was from the last generation of Americans raised under the banner of the common good — the we, not the I, when democratic government claimed to serve all of the people, to protect us all and care for the most vulnerable.

AN ARTIST OUTSIDER

Wojnarowicz began as a writer and his mature artwork increasingly incorporated texts with imagery. The exhibition begins and ends with the sparest work and the most straightforwardly moving. “Arthur Rimbaud in New York”(1979-798) is a series of modest black and white photographs showing a young man in undistinguished, urban settings: on a bare street at night, in an abandoned building, on the subway. Clearly a stand-in for the artist, the figure wears a mask of the young Rimbaud, taken from a well-known photograph. The French poet, who abandoned writing by the age of 21, had inspired previous writers for his poetry and his stance as an outsider and an unapologetic lover of men. The gallery includes the simple but haunting mask Wojnarowicz used, and notebooks that indicate just how carefully he planned each shot.

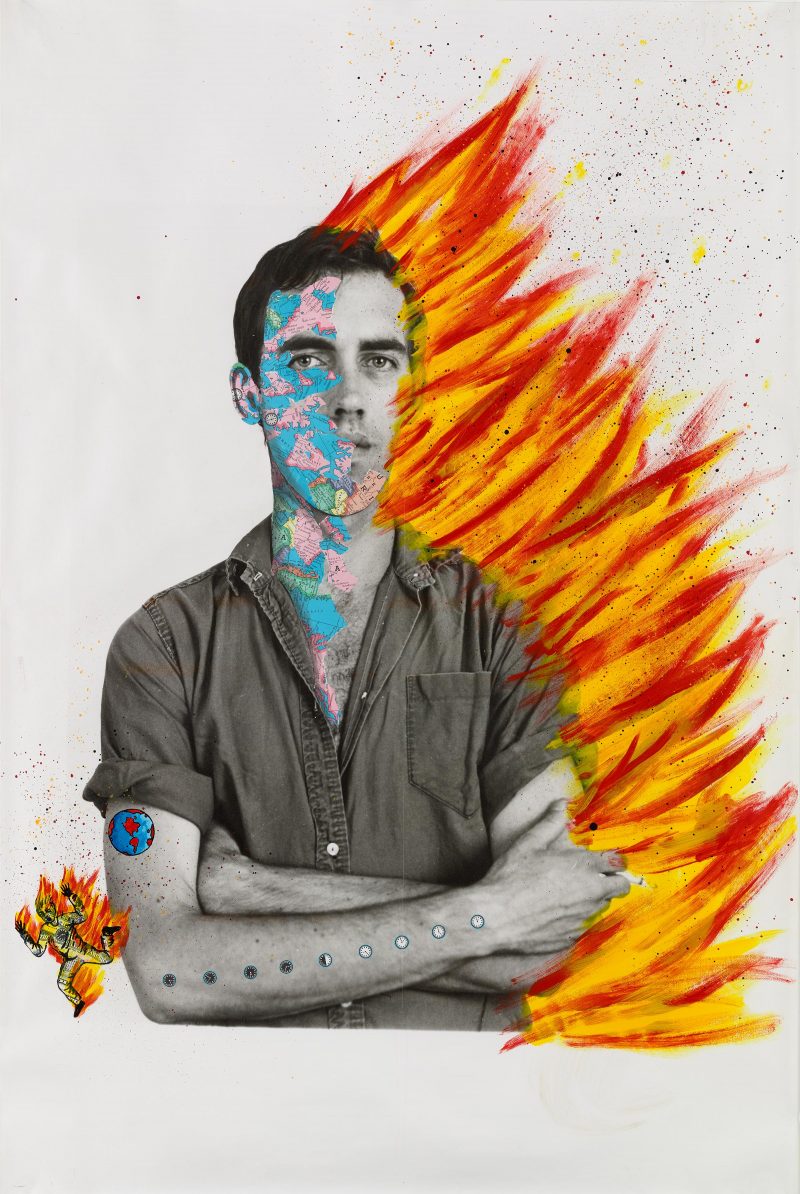

The second gallery situates the beginnings of the artist’s collaged and stenciled paintings and sculpture amidst the visual cacophony of the Lower East Side, where young artists, writers and musicians and equally young dealers established a community; some took their art to the streets as graffiti, posters, and installations in vacant lots. We see a developing vocabulary of images that would recur throughout Wojnarowicz’s career, much of it taken from comic books, television and other American popular culture directed at boys: cowboys, soldiers with rifles, monsters, dinosaurs, steam engines, airplanes. To these he added maps, industrial machinery and landscapes, volcanoes, fires, human organs, microbes, a dancing man and scenes of nude men pleasuring each other taken from gay porn.

PAINTING HISTORY

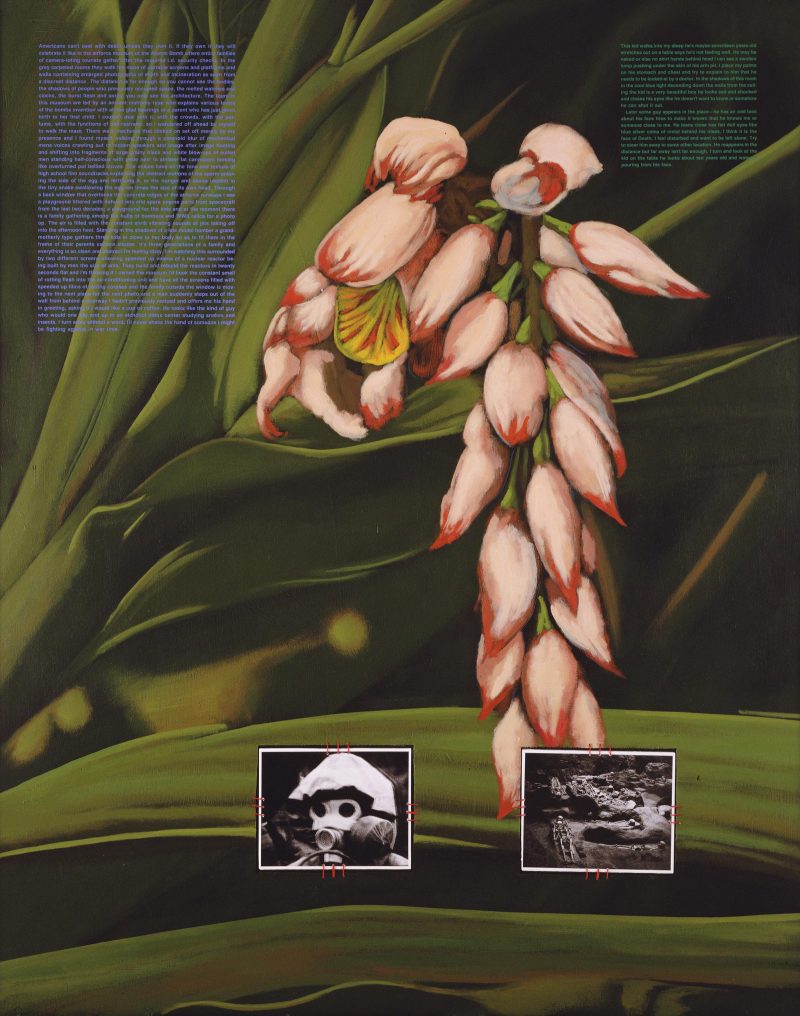

A central gallery is hung with large, history paintings — that is, paintings of important, human concerns which had been the major genre in European painting before Impressionism; his dealer, Gracie Mansion, actually billed them as such. Their theme is apocalyptic, and they bear more than a passing relationship to the nether parts of early Christian depictions of the Last Judgment; Wojnarowicz knew the history of Christian imagery and regularly included collaged details of religious paintings in his work. “Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water ”(1986) approaches the post-disaster quality of Peter Blume’s depiction of fascism’s threat in “The Eternal City” (1934-27, MoMA). Wojnarowicz’s art is pervaded with ethical questions of what we owe each other, of whether we accept responsibility for those who face dangers to which we are immune, of the meaning of community, of the place of death in life, and of the place of beauty in the face of death. The question of how to live a life of meaning was present throughout his life and gives his work its ongoing currency.

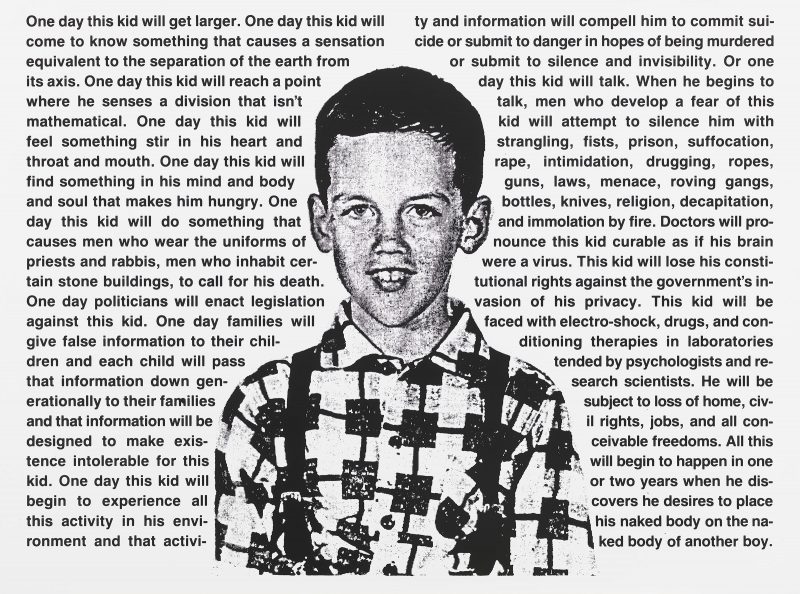

One particularly moving gallery has nothing on view, but provides benches where visitors can listen to the artist during public readings from his work; with assured voice he propels a forward rush of pages of thoughts undivided by punctuation, and his tone is rage. The work in the last two galleries increasingly features more and more text, including his best-known, “One Day This Kid…”, in which an elementary-school aged, fresh-faced Wojnarowicz is shown surrounded with a text that lays out the hatred to which he would be subjected some years after the photograph was taken, when he would discover that he loves boys.

THE CATALOG PAYS TRIBUTE AND RAISES NEW QUESTIONS

David Breslin and David Kiehl. eds, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art and Yale University Press; New York and New Haven: 2018) $65, $49 at Amazon Smile for Artblog

The exhibition catalog is stunning with beautifully-printed illustrations and extremely handsome design. Curator David Breslin’s essay is a personal and moving response to the work. He situates it within an ethical concern for the other which he discusses in terms of Emmanuel Levinas’s writings. The second curator, David Kiehl contributes catalog entries — something almost never done these days with contemporary artworks, and an indication of the care and respect put into his ten years’ research towards the exhibition. The catalog includes the entire texts from Wojnarowicz’s late works (which sometimes run to more than a page), as well as a selected exhibition chronology, a bibliography, and an index.

Wojnarowicz’s biographer Cynthia Carr contributes emendations to the biographical dateline the artist wrote in 1990. [Ed Note: Read Roberta’s 2012 review of Carr’s book, Fire in the Belly]. Gregg Bordowitz, an artist in the East Village community, discusses Wojnarowicz’s readings, his stance as an outsider, contemporaneous writing on allegory and theory of the self and their bearing on his methods, formats and intent. Another artist, Julie Ault, creates a picture of the artist’s interactions with his peers in a collage of texts by Wojnarowicz and people around him. Novelist Hanya Yanagihara emphasizes the artist’s writings in terms of his own times and within the longer history of American writing, and Michael Taylor discusses Wojnarowicz’s deepest religious impulses, manifest throughout the artist’s archive which Taylor accepted for NYU’s Fales Library, initiating their archival collection of downtown artists.

The foreword by museum director Adam D. Weinberg raises topics I would have liked to learn more about. Wojnarowicz was known to disdain institutions of high art, such as museums and upscale galleries, and was ambivalent about his inclusion in the 1985 Whitney Biennial. I would have liked further discussion comparing his work, thematically and in terms of format, to that on view in the commercialized art world he rejected, as well as to that of his East Village peers. Weinberg also refers to the Whitney’s involvement with art of protest movements, some of which has been on view during the past year. Did Wojnarowicz leave any record of his response to contemporaneous protest art by the Guerilla Girls, to prior art related to the Black Power and anti-Vietnam movements, to workers’ movements such as that of California grape pickers, or possibly earlier art of the 1930s? To what extent might any of these have been a model he either consciously followed or rejected? The research on Wojnarowicz clearly offers great potential.

David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night is on view July 13 – September 30, 2018 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, NY

Other exhibits in New York running concurrently:

The Unflinching Eye: The Symbols of David Wojnarowicz on view in the Mamdouha Bobst Gallery, NYU, July 12-Sep 30, 2018

Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins: The Installations of David Wojnarowicz, July 12 – August 24, 2018, P.P.O.W.