This summer I drove down to the Baltimore Museum of Art to see Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1963-2017, which is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art‘s Breuer building through Dec. 3. I approached this sculpture exhibition by the recently-deceased artist, who was known primarily as an abstract painter, with an open mind. I found one of the most seductive and beautiful exhibitions I’ve seen in ages, installed with an artist’s sensitivity to space. The sculptures on view were created over a period of more than fifty years, yet never exhibited, so the exhibition will be a surprise for anyone who thinks they know Whitten’s work.

Jack Whitten (see Justin O. Walker’s 2017 review of Whitten’s show at Hauser & Wirth) experimented with sculpture in the early 1960s, and seven of those early works are included in Odyssey, but the bulk of the exhibition consists of a body of work he created in Crete, where he made annual trips beginning in 1973, and where he eventually built a house and studio. The exhibition also includes a dozen late paintings which the artist called “Black Monoliths” — each dedicated to a public figure or friend. The sculpture is both timeless and entirely of its time: timeless because of the primal nature of wood carved to leave clear marks of its maker, of its own time because it includes detritus of the natural world and contemporary life, including computer boards. But other than the inclusion of found objects it stands apart from most recent sculpture.

Aged in Wood

The biggest surprise for me was the artist’s decision to carve wood, a medium rarely seen during the 1960s or in mainstream contemporary art institutions. Along with ceramics, carved wood must have been among the first art materials of early man; unfortunately, organic material does not often survive. Whitten’s turn to wood carving was directly related to his study of both African art and early art from the Mediterranean, and his work clearly acknowledges these debts. Although examples of his sources are included throughout the exhibition, his interest went well beyond the formal. Whitten was overwhelmingly interested in the social and spiritual place of these masks, headdresses and statues within their societies. In the process he was also recovering part of his own history. Raised in segregated Bessemer, AL, far from any museums, he educated himself from books and the collections of New York’s museums and dealers.

Whitten began most of his sculptures by responding to the crooks, bends and changes in direction of growth of a single, massive piece of wood. His carving honored the life and personal history of the tree from which it came while also leaving evidence of his own spirit and hand. Whitten’s work expresses an interest in spirituality, if not an identification with established religious belief, and he clearly respected the prior life of his materials.

All the Little Things

Much of the work includes accretions of natural or man-made objects such as nails, screws, small animal skeletons, pebbles, wire, bottle caps and circuit boards, which the artist scavenged on his beloved Crete. Some of these often-fragmentary objects are gathered and displayed within glass-fronted containers, which obviously reference shrines. Others are affixed to the carved wood in the manner of Central African minkisi, and consistent with their intention to convey spiritual forces.

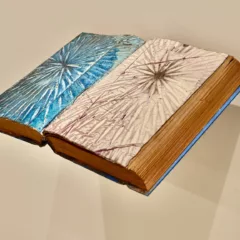

Whitten kept extraordinary notebooks. In them he laid out his artistic thinking on a daily basis — the problems he set himself and his ongoing articulation of meaning in abstraction. Odyssey:; Jack Whitten Sculpture includes pages from these notebooks along with various studio tools and photographs of his bulletin board filled with those artistic and personal images that he chose as company within his working space.

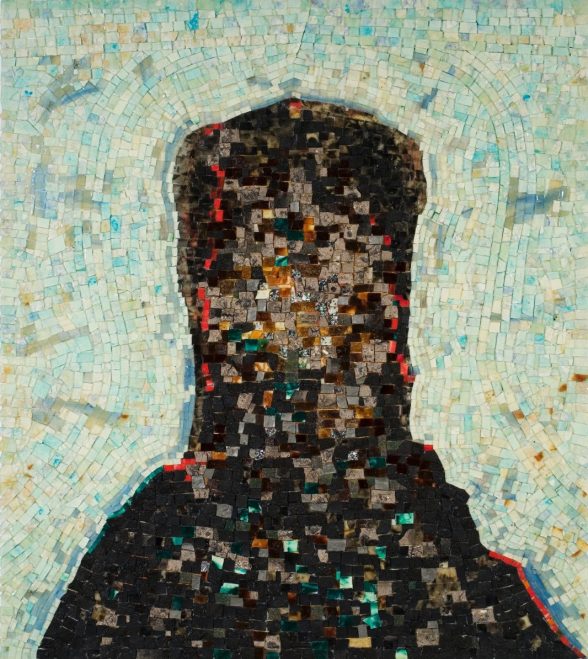

Black Memorials on Canvas

The Black Monoliths, inspired in part by a huge stone outcropping that sits above his home in Crete, is a series of large canvases – one more than 20 feet long – for which Whitten created his own, original technique. He first made small tiles by pouring acrylic paint mixtures into molds, then set them (and occasionally other materials) on the densely-textured black surface of his canvases, creating patterns in the manner of tile work. The accretion of small parts within a larger composition paralleled his sculptural practice. Each painting is dedicated to an African-American public figure, many of them artists and musicians. These personal yet monumental works are Whitten’s answer to the challenge of making abstract memorials — something Maya Lin demonstrated was truly possible.

This stunning exhibition should be fairly accessible to audiences, with or without knowledge of the many artistic issues that Whitten addressed. It was organized with help from the artist, but his death last year has turned it into a memorial exhibition. It is a fitting tribute.

Siegel, Katy, ed. Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1963-2017 (Baltimore Museum of Art and Gregory R. Miller & Co., Baltimore and NYC, 2018) [Amazon]

The exhibition catalog is beautifully illustrated and designed. In addition to essays by curators Katy Siegel and Kelly Baum it includes catalog entries on each exhibited work and an interview with the artist. It also includes Whitten’s essay “Why Do I Carve Wood?,” in which he identifies his years of carving as the single most important influence on his paintings. There are further essays by four other scholars and a chronology by the artist.

Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1963-2017; on view April 22-July 29, 2018 at the Baltimore Museum of Art and September 6 – December 2, 2018 at the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10021