Homecoming. I see it in the trees in Shanghai, with shapes that feel rounder, more stout and dear than the wild, scraggly heart of Pennsylvanian woods. I feel it in the air. This homecoming is like osmosis. I breathe it in, and it permeates my being like a sense memory — or is that just the humidity of July by the sea? This is the place where my parents grew up, and these streets are painted so thickly with stories that I wonder if I’m really seeing anything at all. Which street was it, where my mom skipped school to buy a little paper bag of popcorn with a stolen nickel? As she tells it, this traveling street vendor was the only man in Shanghai with a popcorn machine. The line took all morning, but the prize was worth the wait.

She recounts the whole tale with a joy she reserves for this kind of stuff, all the way through getting walloped by her teacher in the afternoon. I’m not even within an hour’s bus ride of the right neighborhood—it’s none of these streets, yet somehow all of them. This romance survives the entire trip from the airport to my grandmother’s apartment in Waitan, the district across the river from Pudong. For anyone unfamiliar with Shanghai’s layout, Pudong is the part of town on the first page of a Google image search. It looks a bit like Blade Runner 2049 with less lipgloss and brand loyalty—an architect’s playground. Though I’ve been here before, the sight remains shocking. My nostalgia begins to fray over the next two weeks. Little incidents pull at the threads: a combination of my poor Mandarin and a Chinese face causes a lot of miscommunication, particularly in a country where getting on the subway requires a minor security checkpoint. Like a lot of children of immigrants, my relationship to the place my parents are from is several decades behind the times.

The difficulties of navigating language and space lead me, ironically, to spend most of my free time in museums—the only architecture in China where I really feel at home. Though loaded with complicated histories and objects and labels I can’t read, museums everywhere seem to request similar contracts of their viewers: pay for a ticket, follow the map, look at stuff, and you can’t get too lost if you don’t leave the building. My mom, my brother, and I spend most of the trip with extended family in Shanghai, but we take a 4-day detour to Xi’an, a city in central China with a rich history: it’s been the capital of multiple dynasties, and the terracotta warriors are just an hour outside the city limits.

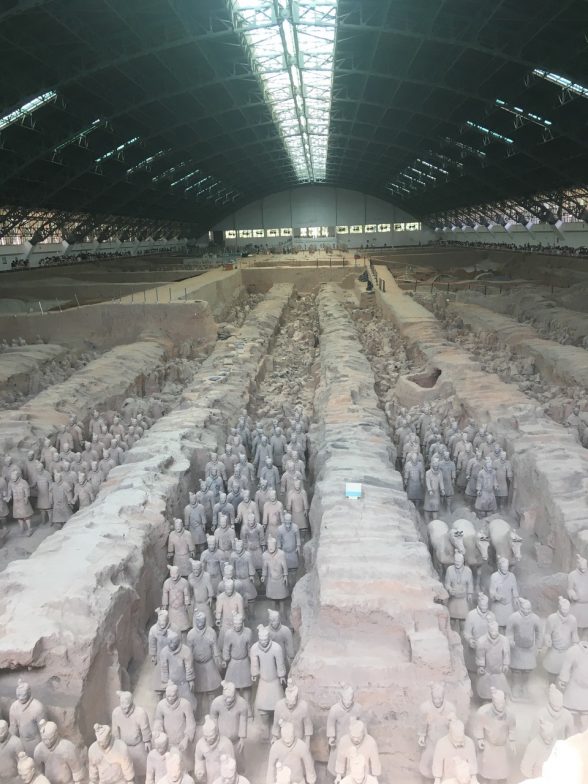

Terracotta Army at the Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang

The first day, we head to the Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang to see the Terracotta Army. If you’re traveling with someone who can read Chinese, it’s possible to take advantage of incredibly inexpensive public transit: the bus to the Terracotta Warriors Museum takes over an hour, but we pay about a dollar for a seat. Through the window, there’s architecture that feels like science fiction. Gargantuan condominiums are erected in open fields and arranged in identical rows. It’s strange to pass by such new things on the way to this incredibly old site. It’s TARDIS whiplash.

The terracotta warriors were created as funerary art for the tomb complex of Qin Shi Huang (259 BCE — 210 BCE), the first emperor of a unified China, previously comprised of numerous small states and locked in over two hundred years of warfare. The mausoleum itself has never been excavated due to conservation concerns, and many artifacts remain buried—but hundreds of figures have been restored and arranged in phalanxes. Each of the three main excavation sites is housed inside massive, cavernous buildings scattered throughout a park with rambling walkways. The buildings are like vast, steel, barrel-vaulted tents above the artifacts. I love that the objects are still living in same plot of earth, that there remains something tomb-like to this place. There are tons of people, and it’s really difficult to shove my way to the front of the crowd—but it’s worth it. The figures are the result of a sophisticated molding and casting process, but looking closely reveals subtle differences in each face.

The figures stand stoically, but there is consistent, almost-imperceptible sloping in the shoulders, and roundness in the shape of the armor. They are abstracted with softness, and although it’s subtle, perhaps these sculptures foretell the wild abstraction of the Han dynasty to follow, where figures of dancers are sculpted like ribbons of water. Here, this softness feels at odds with these stiff military ranks, and it’s a poignant thing.

The main excavation pit is designed so that museum visitors can walk around the building’s perimeter. The site is actively undergoing excavation, so the front half of the room is full of restored statuary, whereas the back is full of fragments, carts, equipment, and clay bodies, half-pieced together and bound with cloth. I love that I can see bits of the messy process of archaeological restoration—it’s an experience I’ve never had in an American museum, where conservation labs often serve a dual role in educating the public. Those are performative spaces. There’s something incredibly unpretentious about this room full of bits of clay, and dusty plastic bins.

Banpo Neolithic Village

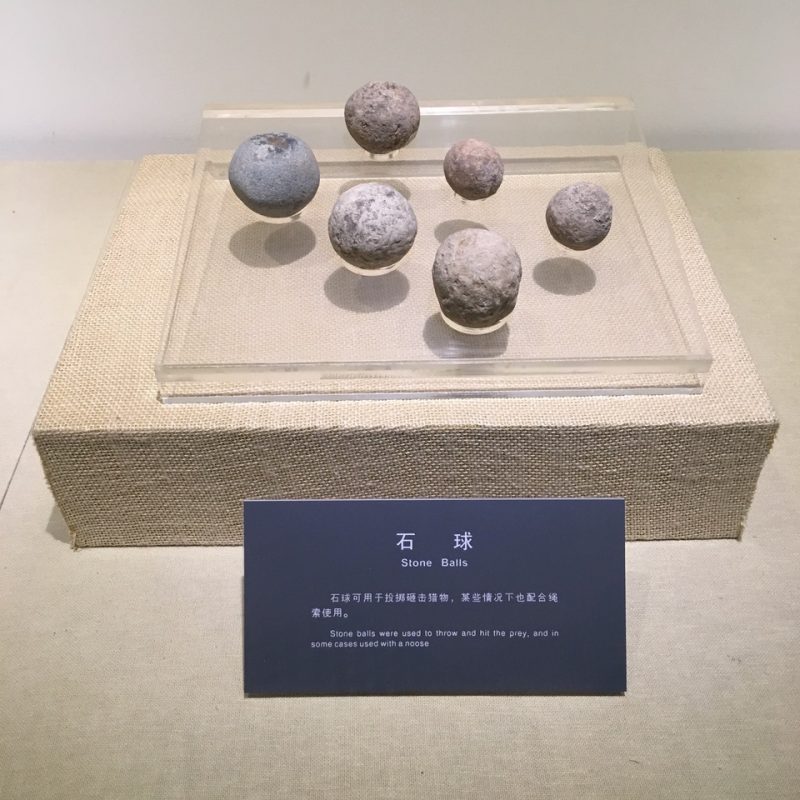

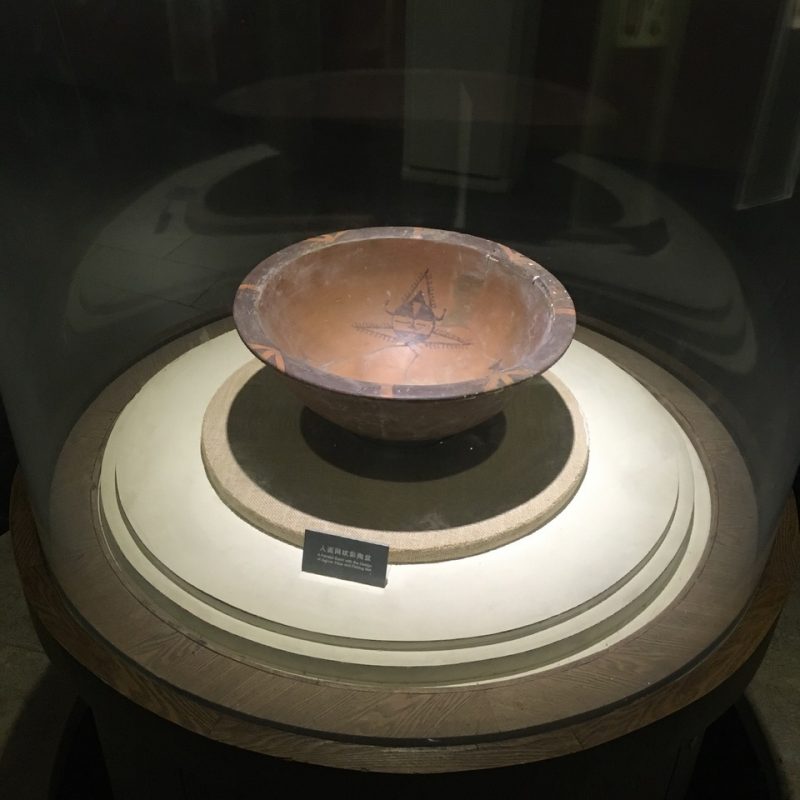

Xi’an is also the home of the Banpo Neolithic Village, one of the oldest archaeological sites in the country at 6000 years before present. When my mom and I get to Banpo, there’s barely anyone else there. It’s a far cry from the one million people who see the Terracotta Warriors each year. Banpo was my favorite stop on our trip, by far: full of humble stuff like stone axe heads and spheres used for throwing (displayed in a clear tray like cosmic orbs), the museum also contains the most gorgeous and awkward ceramics. There’s everything from pinch pots to sophisticated jugs, not unlike amphora. The desire to decorate utilitarian things is so wonderfully human. All the ceramics make me think about the joy of material discovery. A bowl has beautiful and simple geometric patterns. There’s a sculpture of a bird’s head — crude and covered in carved pits, the curve of the beak looks remarkably life-like. A pot is covered in a pattern made with someone’s fingernails. I can’t help but imagine pushing my fingers into the wet clay. I’m standing where the pot’s maker would have stood. I’m in this space with these objects, and it’s a strange intimacy we share. Time is the only thing between us.

For more Artblog posts on China, see Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia’s 2012 2-part feature on the contemporary art scene in Beijing,(Part 1) and Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou (Part 2); and their 2008 post from Shanghai.