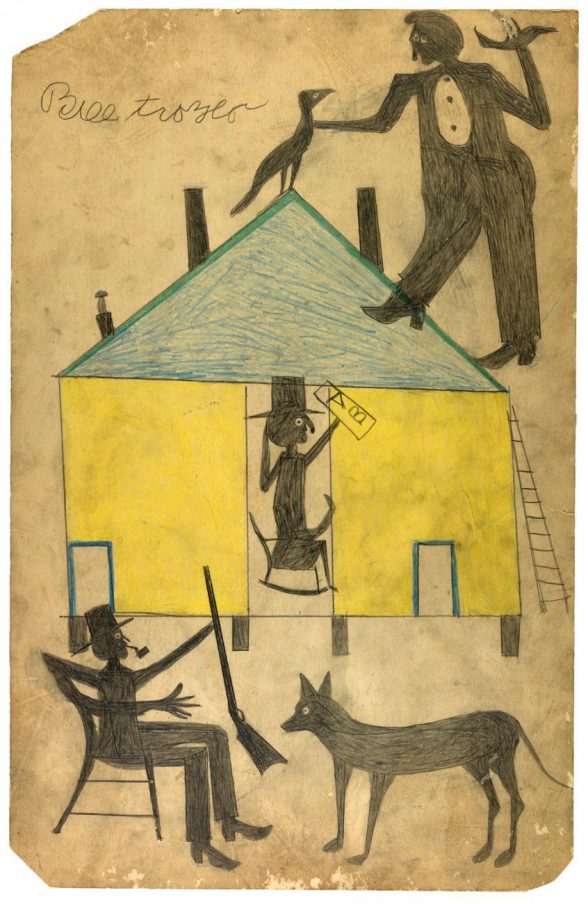

Bill Traylor’s singular art is compelling for the range of emotions with which it invests its human and animal subjects, the vividness of the activities and interactions that it depicts, and its extraordinary graphic sensibility, expressed with the most modest of materials and tools. Traylor drew on various and often irregular and re-purposed pieces of cardboard and in his best work, the spaces around the figures are every bit as interesting as the figures themselves.

The reputation of Traylor’s art will always be intertwined with his biography; Traylor (1853-1949) was born into slavery in rural Alabama and was forbidden even the most basic formal education. He did not begin to draw and paint until some time in his 80s, a decade after he had moved to Montgomery. Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through March 17, 2019, is a serious accounting of Traylor’s achievement. The exhibition, and especially the detailed and seriously-researched catalog, investigate his many references to often un-recorded African and African American religious and social practices, stories and traditions. These Traylor expresses in a coded way designed to disguise their content from the white population that first enslaved African Americans then ensured them a marginal existence, despite their supposed freedom.

The history of artists such as Traylor is marked by the inherent power and financial imbalances between the artists — often poor, rural, of color, and of limited formal education — and the dealers, collectors, curators and scholars who have addressed their work. Between Worlds is exemplary in addressing Traylor’s development as an artist, despite the relatively short period over which he worked, and the range of sources from which he drew. Curator Leslie Umberger has done a remarkable job in researching an artist for whom traditional documentary sources are lacking, largely due to the coded and orally transmitted nature of his subject matter.

The exhibition avoids treating Traylor’s art as charming, timeless or rooted in the imaginary — pointing out that the violence and conflict frequently depicted are based upon his own experiences and those of his community. Traylor worked on the streets of Montgomery and often hung his work around him for passersby to see. Although it is doubtful that he made much money from his art, he was known to sell work from time to time and it would be fascinating to know about his interactions with the segregated black community in which he lived. We do have significant documentation from the white artists in Montgomery who supported his work and bought it in quantity, ensuring the survival of his reputation.

That said, an exhibition of 153 detailed works with annotated labels only makes sense for specialists; non specialist visitors will likely be unable to see it all and should probably not try. The general public would have been better served with one third the number of works, and a few, large introductory labels to indicate that each of Traylor’s drawings deserves time to appreciate. SAAM is not alone in falling for the mistaken but very American idea that bigger is better. If the museum thought that Traylor merited a large exhibition to emphasize his importance, it has worked against the general appreciation of his artwork. The substantial catalog, however, is a major contribution to American art history.

“Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor,” on view September 28, 2018 – March 17, 2019 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 8th and F Streets, NW, Washington DC, 20004. Gallery hours, Monday-Sunday, 11:30am-7pm.