When I attended “White Feminist” at The Skinner Studio, a third-floor performance space at Plays and Players, I sat in the back row next to the entrance steps and placed my notebook against the banister while the room filled up with eager patrons. As seats ran out, a crew member placed two more chairs directly in front of me and said, “Sorry, we’re going to trap you in.” Now completely unable to exit and slightly exasperated I thought, well, depending on how the show goes, this might be a fitting anecdote to share.

“White Feminist” was one of two shows I saw during the Fringe Festival as part of my inquiry into feminism and theater. The second show was “The F Word” hosted at Asian Arts Initiative. “White Feminist” was a one-woman performance starring Lee Minora as Becky, a cheery tv talk show host who aims to be a feminist hero but, as the name implies, exemplifies the harmful qualities of white feminism (exclusivity, privilege, e.g.). “The F Word” is a musical from Radiant Bloom Productions and features five women—Demetria Bailey, Erica Cochran, Heeya Kim, Kalyn West, and Meredith Beck—who combine pop and historical music to chronicle feminism in America.

“White Feminist” and white privilege

Can a white person make fun of their whiteness in front of white people in a way that’s productive and not self indulgent? Before seeing “White Feminist” I would have said no. It’s fair to say the piece had an uphill battle to win me over, and for a brief moment I thought it could. This was in large part due to Lee Minora’s skilled improvisational performance as Becky. Early on in the show — in which audience was addressed as if they were the audience of Becky’s talk show — Becky conducted an audience survey of sorts asking, “Who voted? Who Instagrammed that they voted? Who texted ‘resist’ to a bot this year?” Becky/Minora teased out honest answers from her audience and made every question a set-up for the punchline.

Unfortunately, there was not much criticality on the other end of the laughter. Early in the performance Becky had the audience repeat the slogan of her show, “Today, we’re all Becky!” which everyone did with great enthusiasm. In this space Becky supported the audience’s shortcomings and needed their support in return. She prompted the audience to give her compliments and had people constantly reassure her that she was a good person and was doing a good job on her television show. It was impossible to tell if audience members were playing the role of a supportive studio audience for the sake of “staying in character” or if they genuinely believed she was well intentioned and deserved constant reassurance.

“White Feminist” reached a climax when Becky was forced to read a “live tweet feed” of criticisms of her talk show. Here her character’s privilege was addressed head on. Becky responded by going on a long tearful tirade of apologies. She apologized for being exclusive, and for the cis white women taking up too much space at the 2017 Women’s March. She said she keeps apologizing and doesn’t even know for what anymore.

After the tears and the apologies, Becky told a traumatic story of being sexually assaulted by her CEO. It was a moving and honest monologue that explained the intricacies and confusion a person faces in an abusive situation. When she finished the story, she looked back at the live Twitter feed and saw now that everyone was back on her side and calling her a hero. The show ended with her feeling triumphant once again.

It is not fair and it is not right for a white woman to use a story of sexual assault to get off the hook for harmful behavior. I have serious concerns about how this moment was used to ensure Becky was back in favor with her real and imagined audience.

Inclusivity and “The F Word”

“We are braver and wiser because they existed, those strong women and strong men. We are who we are because they were who they were. It’s wise to know where you come from, who called your name.” -Maya Angelou

This quote from Maya Angelou’s apparent final interview appeared with great significance in “The F Word.” It was essentially the premise for the entire show. “The F Word,” a lecture-cum-musical was performed by a group of diverse voices. The five women who starred took turns leading songs and enacting feminist history from The Suffragettes, to World War II, to The Civil Rights Movement, to Second Wave Feminism and beyond. Text and image wall projections, run by lighting designer Sarah Gafgen, provided names, dates, and visual context.

Bailey, Cochran, Kim, West, and Beck lent their impressive voices on a range of songs including, “I am Woman Hear Me Roar,” “Respect,” “Sisters Are Doin’ It for Themselves,” “You Don’t Own Me,” and “Me And A Gun.” Miche Braden, the Music Director and Arranger, carried the score with expert piano playing that came right out of the black church. Braden was accompanied by Ryan McCurdy and Jacob Shipley on guitar and percussion. The two men also were players in “The F Word,” taking turns as various white men in history. Sometimes they were antagonistic historical figures or buffoonish husbands. In other scenes they were allies and protesters themselves.

Many voices, some sidelined til the end

The show was a testament to how simplicity and honesty in art can connect us more than abstraction and cynicism. Because of the range of racial and ethnic identities present in the cast, “The F Word” contains a story made up of many, and often clashing, histories. In particular, the struggle between white feminists and black and brown women came up repeatedly, reminding the audience that middle class white women were able to make progress by purposefully excluding others who were not like them.

Sadly, “The F Word” left indigenous, LGBQ+, trans, and disability narratives until the very end, when the cast addressed their lack of mainstream representation in a kind of open forum conversation. While I appreciated the earnest attempt to bring the discrimination these folks face to light and the specificity with which this discrimination was explained, it felt somewhat contradictory to omit these overlooked narratives until the very end, like an afterthought, and then criticize mainstream feminist culture for leaving them out as well.

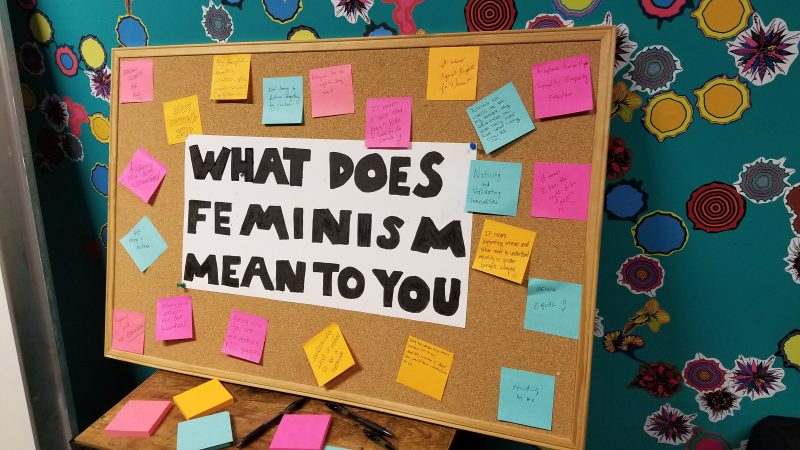

Director Lauren Widner and Writer Irene Molloy created a show that explored the complexity of feminism, past and present, without trying to define it. In fact, outside the theater, a board bearing the prompt, “What does feminism mean to you?” invited audience members to fill it up with sticky notes of their own ideas. The deficiencies and triumphs of feminism in America have always existed side by side. “The F Word” is not only about feminism, but seems interested in doing the work feminists need to constantly do: learn their history, self reflect, listen to others, and build strength in coming together.

“White Feminist” ran September 12-16 at Skinner Studio at Plays & Players Theatre, 1714 Delancey Place, 3rd Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19103. “The F Word” ran September 15-18 at Asian Arts Initiative, 1219 Vine Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107.

Links to people mentioned in this article:

Lee Minora

Demetria Bailey

Erica Cochran

Kalyn West

Meredith Beck

Maya Angelou’s Final Interview

Sarah Gafgen

Ryan McCurdy

Jacob Shipley

Lauren Widner

Irene Molloy