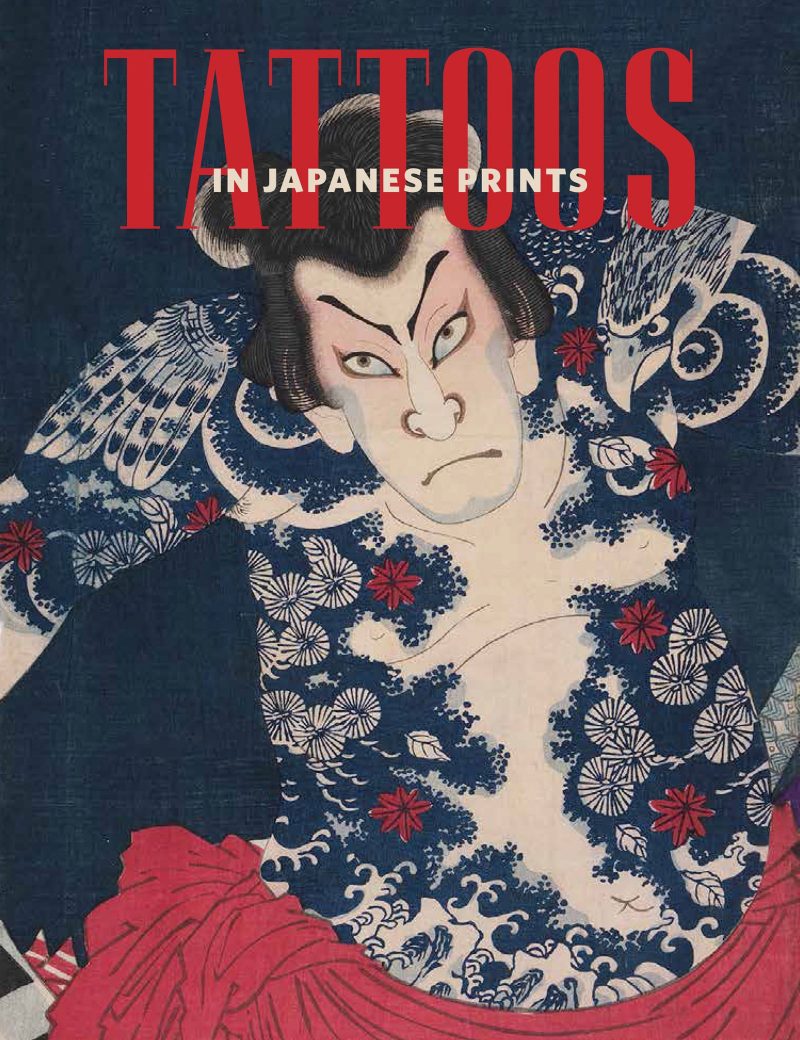

Sarah E. Thompson, Tattoos in Japanese Prints (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 2017)

This delightful book will entertain fans of Japanese prints and provide a wealth of information and ideas to anyone interested in tattoos. Many consider Japanese tattoos to be the greatest examples of the craft and when the country re-opened to foreign travelers under the Meiji in 1868, numerous Western visitors returned with them, including the future King of England, George V and the future Czar Nicholas II of Russia. These are a few of the tidbits that Sarah Thompson reveals in her introduction to the book, which is illustrated with prints from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA).

With respect to tattooing in Japan, it is unclear whether art copied life or life, art. In the late 1820s Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1789-1861) created a series of woodblock prints of Chinese warrior-heroes, many of whom he depicted with tattoos which had not been mentioned in the texts from which he drew his images. The prints became best-sellers and extensive pictorial tattoos were all the rage. Tattoos in Japanese Prints begins with a late 18th century print by Kitagawa Utamaro of a courtesan tattooing her name on her lover’s arm, and proceeds with numerous images by Kuniyoshi and later artists — the majority of which illustrate actors in various guises. The final print depicts Japanese soldiers during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05 wearing modern, Western uniforms with tattooed porters in traditional garb. Thompson’s entries for each image cover a broad range of subjects from legends, history and social customs to clothing.

Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool (Nasher Museum of Art and Duke University Press, Durham: 2008)

Anyone who has seen a painting by Barkley Hendricks (1945-2017) is unlikely to forget it, and this handsome and well-organized catalog for a 2008 exhibition (organized by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University) is the only monograph available on his work. The artist is best known for life-sized, full-length portraits, begun in the 1960s, of street-smart African Americans who were rarely seen in the grand format of large oil paintings. These subjects were artists in their own self-presentation and the paintings read as collaborations between Hendricks and his sitters. They have attitude – and clearly don’t give a damn what we, the viewers, think of them.

Hendricks was ahead of his time – or more properly, timeless. His paintings can be dated by clothing styles, but otherwise look as though they might have been done last year. The exhibition of ten years ago was certainly ahead of its time – which is why this reprint of the catalog is especially welcome. In 2008 Hendricks’ work had not been given its due, but changing art world interests mean that his paintings are essential to many contemporary artists; the work of Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas is unthinkable without Hendricks’ precedent. The fully color-illustrated volume, as cool and classy as its subject, contains essays on the work and its importance to younger artists (by Schoonmaker, Richard J. Powell and Franklin Sirmans) and an interview with Hendricks by Thelma Golden. It also includes the artist’s notes on the works in the exhibition, which concentrated on his portraits but incorporated three early abstractions and a small number of his late landscape paintings.

Timothy Hyman, The World Made New: Figurative Painting in the Twentieth Century (Thames and Hudson, London: 2016)

This is a counter-narrative to most histories of twentieth-century painting that privilege abstraction, written by a highly-articulate British painter. It will interest readers who know more as well as those who know less about the orthodox accounts. Hyman reveals his catholic tastes in the book’s introduction: “It might seem a violation to construct any common cause out of such wayward individuals as Max Beckman and R.B. Kitaj, Charlotte Salomon and Philip Guston, Alice Neel and Ken Kiff, Baltus and Bhupen Khakhar, Leon Golub and Stanley Spencer, yet in their different contexts each was linked by their ‘resistance.’” The artists Hyman addresses were aware of the formalist focus of their contemporaries but chose to concentrate on different concerns – primarily man’s psychic and social lives. That some of them, including Kiff, Khakar and Spencer from the above list, have rarely or never been seen by American audiences should only add to the book’s interest.

Hyman is not suggesting that his account is definitive – rather that many artists, some of whom worked far from centers of artistic activity and debate, created compelling work that should be part of a more inclusive story of art in the Twentieth Century. He writes from a position of someone personally engaged with his material and quotes other artists throughout. His examples of modern figuration were nowhere to be seen in textbooks when he was an art student in the 1960s, and both painters and their audiences will be grateful.

Marjan Unger and Suzanne Van Leeuwen, Jewelry Matters (Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and nai010 Publishers, Rotterdam: 2017)**

Amazon

**Publisher is currently sold out of this title.

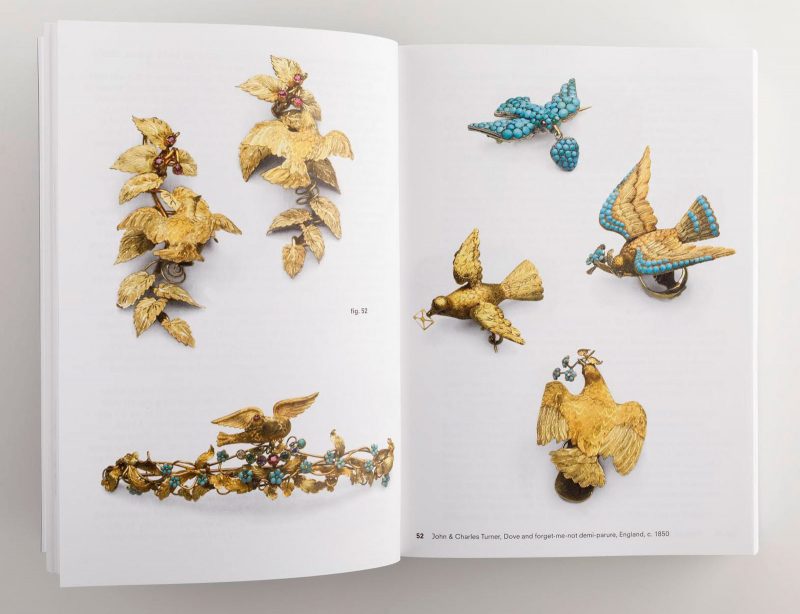

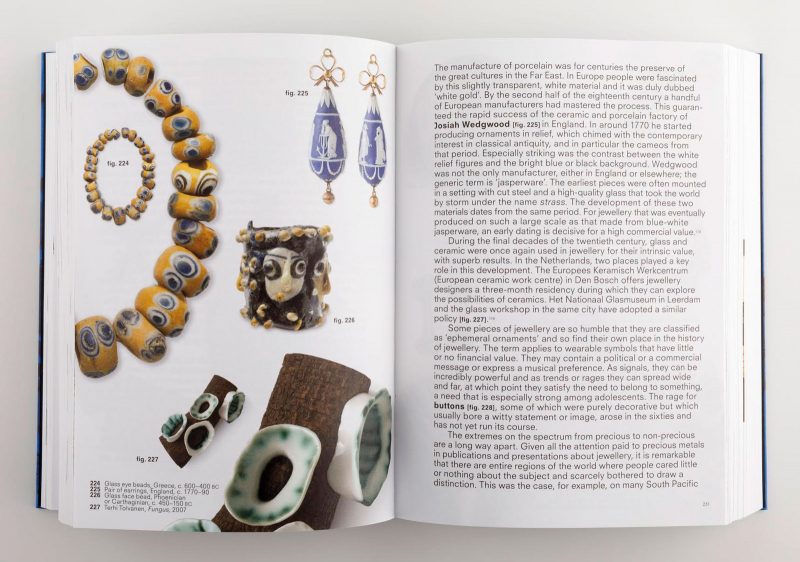

This little jewel of a book, designed like a hymnal to fit comfortably in the hands, illustrates a history of jewelry largely from the Rijksmuseum collection but supplemented with work in other collections — all shown at true size. Jewelry functions in relation to our bodies, and the book design by Irma Boom Office mirrors it’s subject: the title, printed in metallic silver, catches the eye while the blind stamped binding engages the fingers. Unlike the coffee table books that have come out of too many museums’ costume and jewelry departments, the text is not nominal. Rather, this handbook attempts to address the most basic of questions: What is jewelry? Why do people wear jewelry? What do they value about it?

Written in clear and jargon-free language by an art historian and design expert who is also a jewelry collector and by the museum’s curator and conservator of jewelry, the book addresses jewelry as material objects in a social context – drawing approaches from art history, fashion theory and anthropology. The 563 works illustrated reflect the museum’s collection with an understandable emphasis on Dutch material. There is wonderful Renaissance jewelry as well as a strong selection of modern pieces. The book covers considerably more than gems owned by the wealthy, such as ceramic liberation brooches made to celebrate the end of the German occupation in 1945, a child’s flocked, plastic brooch of Walt Disney’s Bambi, and paper poppies worn by the British to commemorate the dead after both World Wars.