A book, an exhibition and love for a well-known Baltimorean

It wouldn’t be going overboard to describe John Waters as one of Baltimore’s most cherished cultural icons, the personification of the city’s quirky, working-class, naughty, catholic (and naughty Catholic) demi-monde. Over the years, as the culture has caught up with the boundary-crossing audacity of his 1960’s and 70’s films, and those films themselves have crossed into the mainstream with Broadway musicals, and spin-off movies made by directors paid far more than Waters ever made in his career, the city has tightened its embrace. A major festival set in the neighborhood that was the backdrop for Hairspray, the 1988 film that launched the career of Ricki Lake, draws thousands each year to partake in a celebration of blue and pink beehive hairdos, cat-eye glasses and leopard prints.

For years an annual one-man show put on by Waters around Christmas routinely sold out Baltimore’s cavernous Lyric Theater, and recent shows at smaller venues in the city are sold out months in advance. (Typical line: “If you go home with somebody after a party and they don’t have any books in their apartment, don’t fuck ‘em.”) He’s such a common figure on the streets and in the watering holes of Baltimore that I suspect that I may be the only person in the city not to have encountered him simply walking down the sidewalk.

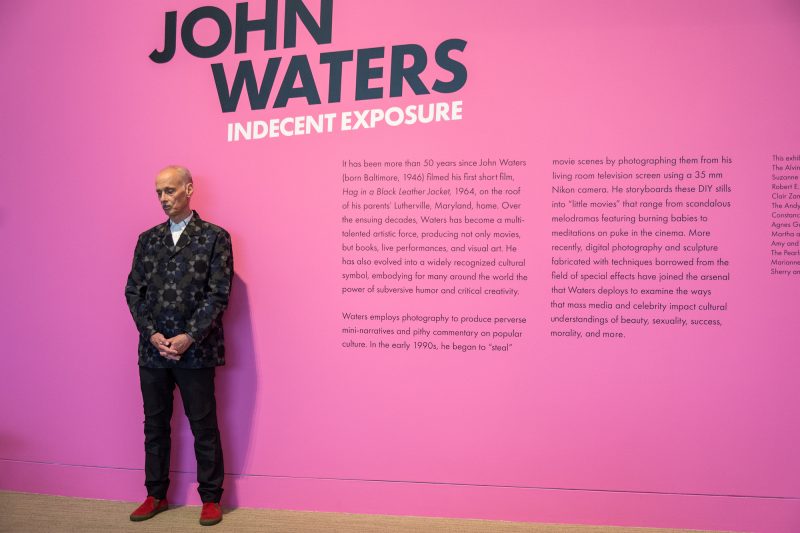

So, it’s only fitting that Waters, who over the course of the past 25 years has produced a wealth of artworks above, beyond, and behind his cinematic products, has been given a substantial solo exhibition by the Baltimore Museum of Art. Indecent Exposure, curated by the BMA’s Contemporary Curator, Kristen Hileman, presents over 150 of Waters’ works, in media ranging from still photography to sculpture. Accompanying the exhibit is a handsome catalog, appropriately covered in slightly-stained brown wrapping paper with a peep-show hole providing a view of a Waters self-portrait altered to show what he might look with extreme cosmetic surgery. Hileman provides a lucid essay placing Waters’ work in context with the appropriation art of Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince (among others), and other essays in the catalog by Waters’ colleagues and contemporaries provide more intimate insights into his art and mindset.

The best ‘splainer of his works is…him

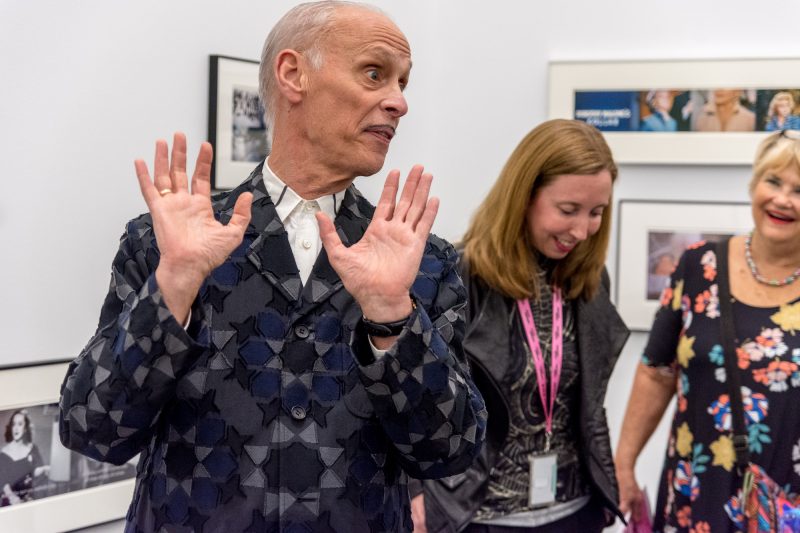

But it is Waters himself who is best at “splainen” his work. No wall flower, Waters is typically ebullient and loquacious. As Hileman points out in her essay, unlike other appropriators, Waters doesn’t borrow the tropes of celebrity and apply them as a kind of generic code to the world at large. Instead he focuses-in on celebrities themselves, exploring the peculiar way in which their almost wholly manufactured aura gives us a personal relationship that has little to do with a truth that is frequently disappointing, and sometimes sordid. But the revelations are joyous, because Waters clearly loves the notion of celebrity, the celebrities themselves, and the whole apparatus of fame and popular culture. In a pre-show media walkthrough of the exhibition, he noted various aspects of the works that weren’t mentioned in the catalog, nor the labels.

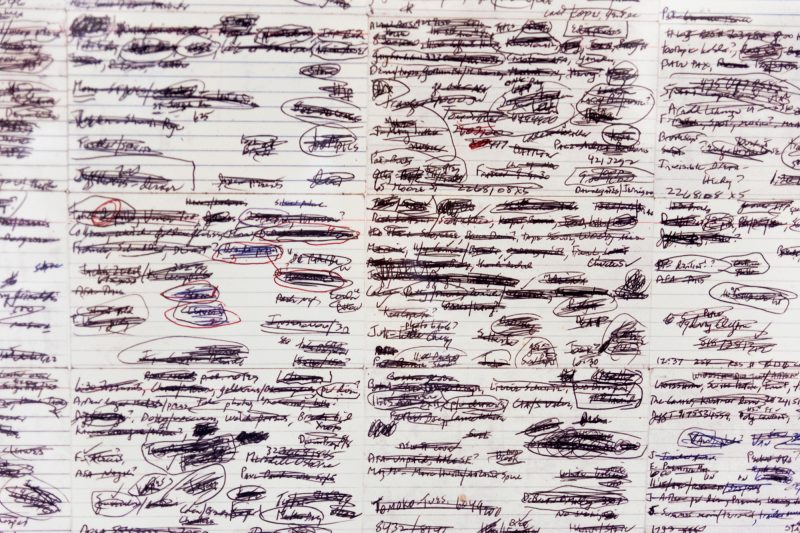

Discussing Movie Star Jesus, a photo collage in the shape of a cross composed entirely of depictions of the crucifixion of Christ from various Hollywood movies, Waters pointed out that the crucifixion scene invariably occurs about three-quarters of the way through a film, at about exactly the same time point that climax (both in terms of plot and physical action) is reached in porn films. In another piece that uses photographs shot of a television screen showing a video Waters made with Divine in the mid 1960’s re-enacting the Zapruder film of John Kennedy’s assassination, Waters explained that as the video aged and was photographed, it came to resemble the original Zapruder film ever more closely, but that Divine didn’t particularly like it, since “Divine didn’t want to be Jackie, he wanted to be Elizabeth Taylor. I wanted to be Jackie.”(Zapruder, 1995.)

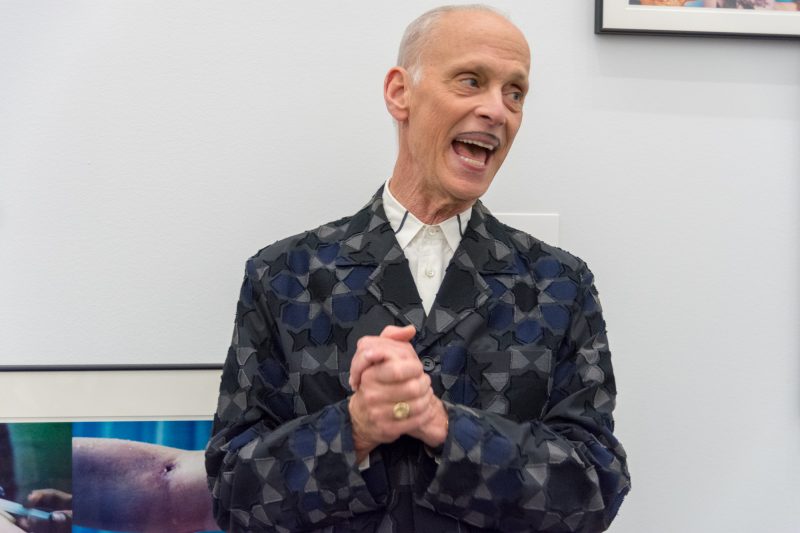

Playful, funny, dark with a touch of sweetness and optimism

A playfulness runs throughout the show, even in subjects dealing with deeply troubling issues. In Faux Video Room, from 2006, sounds of a crowd emanate from behind a black curtain that appears to be the entrance to a typical black-box video room found in many contemporary art exhibitions. But on pulling aside the curtain, one is confronted with a large sheet of plywood, painted black, on which a loudspeaker is mounted. The sounds turn out to be a recording of the Peoples Temple in Guyana, in which Jim Jones is administering the “Kool-Aide” (actually “Flavor Aid”) laced with cyanide to his disciples.

Plenty of works poke fun at the machinery of the art world, including museums. In Art Market Research,” he presents a set of forms supposedly filled out by art research focus groups, in which comments such as “It wasn’t signed on the front” are given in response to a question about what the viewer didn’t like about a Cindy Sherman photo. In the slapstick Hardy Har, a gauzy photograph of an Orchid hangs on a wall, with a taped line on the floor to warn viewers from getting too close to the work. Step over the line, and the flower squirts water in the face of the transgressor.

Perhaps the most touching piece in the show is one that Waters created as the antithesis to the vulgarity his work (the “dirty stuff,” as he might put it) paved the way for in popular culture. In a real video room, a group of elementary school kids are on screen performing a table-reading of a Bowdlerized version of Pink Flamingos, the film that most emphatically launched the careers of Waters and Divine. Perhaps, Waters noted, the most shocking aspect of the piece is its sweetness and optimism, which always lay at the center of the film.

Chuck Patch is a museum professional and teacher, aspiring amateur photographer and sometime

writer. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

Johns Waters, Indecent Exposure,

Baltimore Museum of Art, 10 Art Museum Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218-3898, through January 6, 2019

and

Wexner Center for the Arts, 1871 North High Street Columbus, Ohio 43210, February 2 – April 28 2019