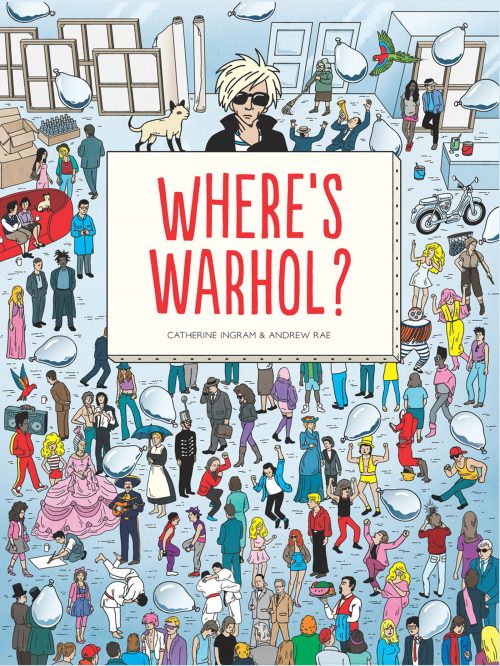

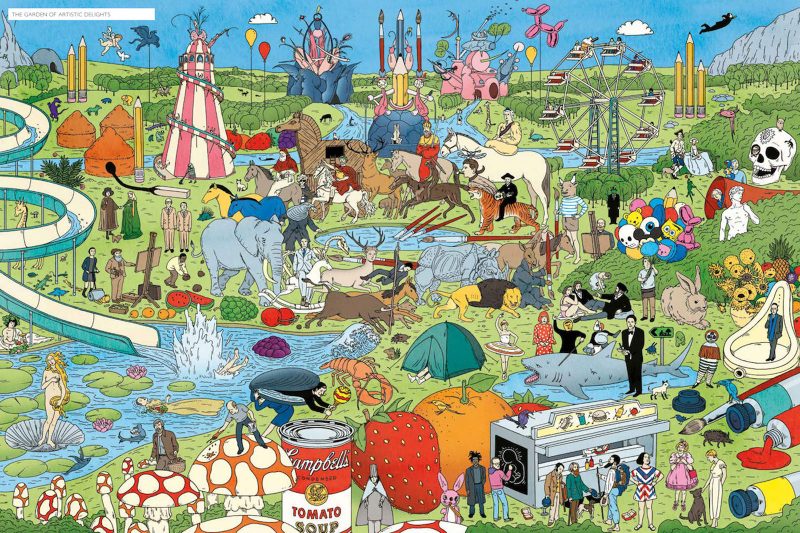

Catherine Ingram and Andrew Rae, Where’s Warhol? (Laurence King, London: 2016)

This is a fun book for adults, and the more they know about art, the better – even though I have only seen it, misfiled, in the children’s section. Yes, it is shamelessly based upon the children’s classic “Where’s Waldo?” but the authors have inserted the eponymous artist into plausible scenes from his life (such as Studio 54), as well as on a romp through history from Pompei to the 1980s. It would make a good party game for a group of art buffs who could vie to spot an Oskar Schlemmer costume, Leonardo’s Lady with an Ermine, Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife, as well as jokes such as John Cage collecting mushrooms marked with Yayoi Kusama spots.

Many, but not all the references to art and history are cited in the back, which might make it the only text and caption-free picture book ever published with endnotes. It contains information explaining the authors’ decisions to choose certain subjects – such as the fact that Andy Warhol bought works by Yves Klein, or that Sigmund Freud, Rachel Whiteread and Anthony Gormley were all fascinated with Pompei. These may sound like a string of non-sequiturs, which they and the book itself are, but the point is play, not art history. Where’s Warhol cites permission from the Warhol Foundation but there’s no mention at all of Martin Handford, author and illustrator of the “Where’s Waldo?” series.

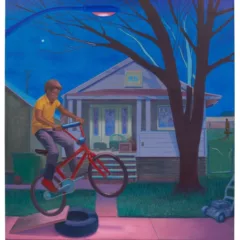

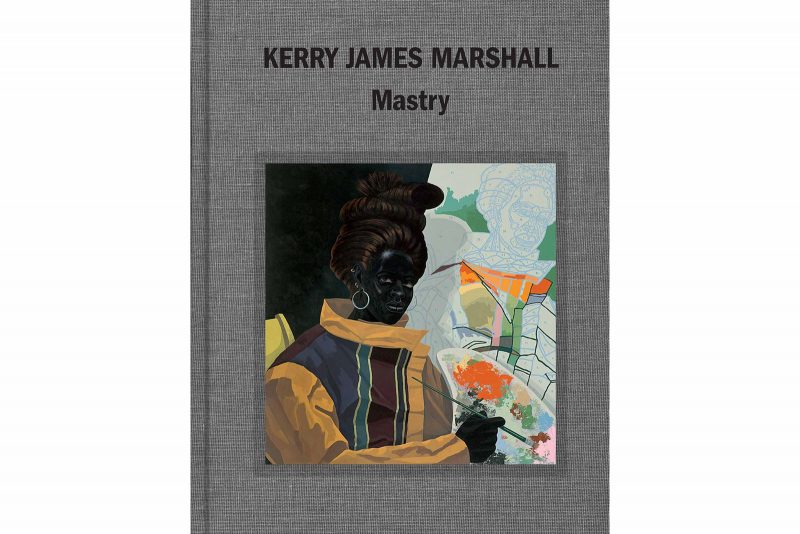

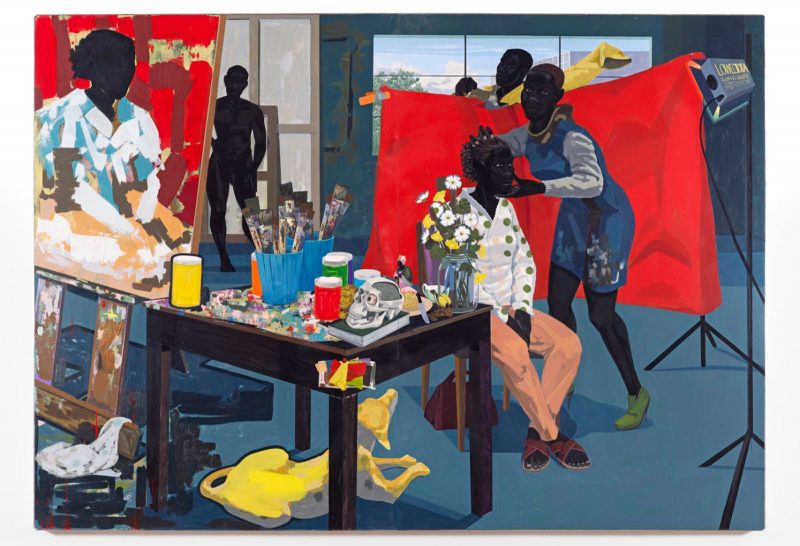

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, Helen Molesworth, ed. (Skira Rizzoli, New York: 2016)

The painter, Kerry James Marshall, has become increasingly influential, but his work has not been seen as widely as his reputation merits. This beautifully conceived and produced catalog for a 2016-17 survey organized jointly by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles is a stunning overview. Not surprisingly, it has sold out repeatedly and is on its sixth printing. Madeleine Grynsztejn’s foreword offers an excellent, short analysis of Marshall’s work, and is followed by articles discussing his education, analyzing his work and placing it within the context of art and social history.

A notable aspect of Marshall’s approach is that he paints figures in black, using relatively unadulterated black paint, rather than in realistic skin tones. Lanka Tattersall offers a valuable discussion of this use of the color by an artist who has been determined to insert black bodies into the history of art, where they have been notably missing. Helen Molesworth suggests that the artist’s determination to attack the traditional Western cannon through the medium of it’s most valued form – painting, especially large, history painting – is a form of institutional critique. The volume includes two additional essays, catalog entries, selected writings by Marshall himself, a selected bibliography and small images of a group of works from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection that Marshall selected to be exhibited in a gallery adjacent to his own work when the exhibition was in New York.

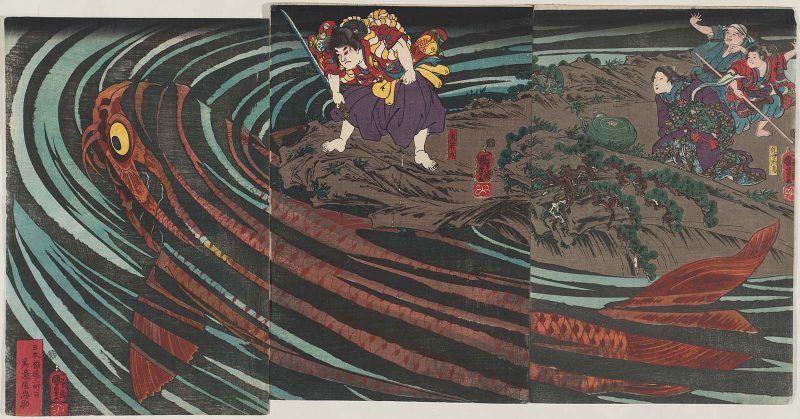

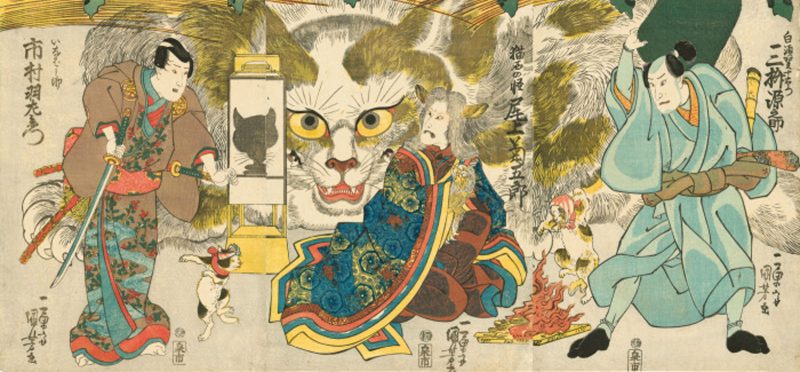

Kuniyoshi: Visionary of the Floating World, Rossella Menegazzo, ed. (Skira, Milan: 2018)

The Japanese print artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1860) was as versatile as any artist who ever lived. His subjects included warriors, ghosts, landscapes, geishas and courtesans, actors, games, jokes, cats and erotica (most of which was humorous and not included here). He could arouse terror and fear as deftly as he provoked humor and had a cinematic ability in bringing to life large scenes full of activity and with casts of hundreds, if not thousands. This elegant and beautifully-produced catalog to an Italian exhibition is a good survey of his work, which is otherwise available only in parts, according to the subject (warriors, actors, cats, etc.) or in collectors’ editions.

Manga and anime would be unthinkable without Kuniyoshi’s influence, and the popular culture associated with those genres is certainly one reason that his reputation in the greater art world is behind that of other giants of Japanese prints. Kuniyoshi overcame the size limitation inherent to Japanese printmaking – the dimensions of available cherry-wood blocks – by creating triptychs with designs flowing across them, such as the body of a giant carp, which merges with the ocean’s waves in a vortex of action overlooked by the hero. His cat prints alone demonstrate his range, and their appreciation requires no particular fondness for felines. But cat lovers will find that no one appreciated them more or was more imaginative in depicting them as heroes, villains, clowns or as parts of letter-forms.

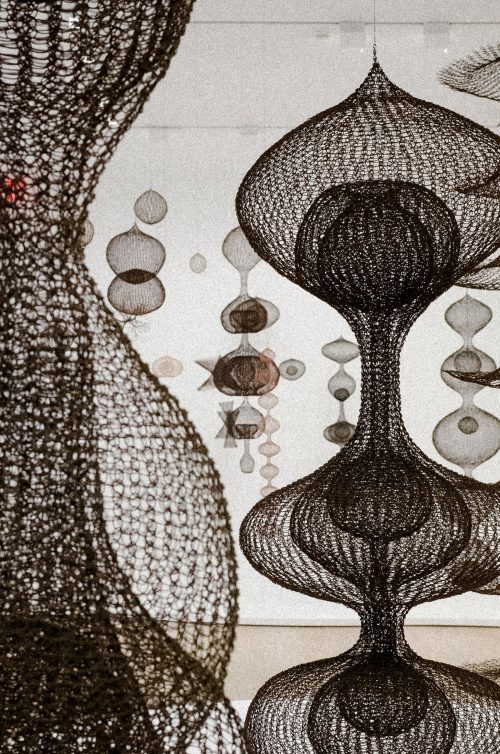

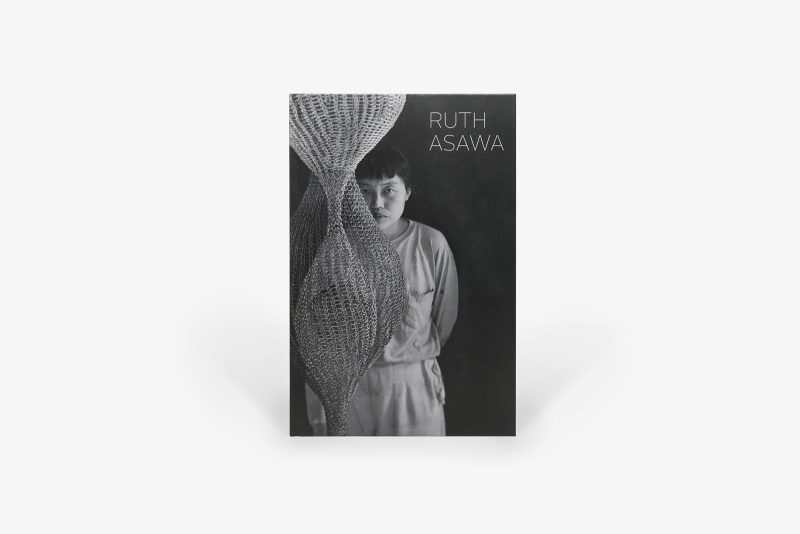

Ruth Asawa, texts by Tiffany Bell and Robert Storr (David Zwirner Books, New York: 2018)

This exquisite book is appropriate to its subject and an excellent introduction to an artist only belatedly becoming known to a larger art world. Ruth Asawa was a highly individual artist whose abstract, biomorphic sculpture and sculptural installations combined fine patterning, organic forms, rhythmic repetitions and cast shadows. She created a technique of crocheting metal wire into transparent forms that resemble basketry, which she more often than not displayed as pendant forms. The delicate but complex patterning of her work at times resembles micro-photographs of organic material.

Asawa studied at Black Mountain College and retained friendships formed there with Joseph Albers and Buckminster Fuller. She returned to her native California and her work was shown in NYC and published in national publications. During the later 1950s and 60s she exhibited nationally in group exhibitions and led a successful and respected life as a San Francisco-based artist and teacher with a regional reputation. Why it took so long for New York to “discover” or rediscover Asawa is beyond me; she died before her estate was taken on by the most fashionable dealer in the world. For readers this will not matter, but it leaves a bad taste in my mouth. I am looking at the catalog of her last, West Coast retrospective (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2010) and it takes no special insight to recognize a major and singular vision and work of universal appeal. If you don’t know Asawa already, this is a fine place to start.