“Girlhood” marks that special moment in the life of a female person when her symbolic potency and (imagined) reproductive value to society are at their zenith while her authority in the world and autonomy in her own life are at an all-time low.

More than a mere solo show, Suzanne Bocanegra’s Poorly Watched Girls stages girlhood’s complex interplay of time, gender and vulnerability in four distinct, immersive environments that swell the Fabric Workshop and Museum. Indebted as much to the world of theater as they are to anything happening in contemporary art, these environments share a refreshingly promiscuous attitude towards medium, combining textile-based craft with film projection and elements of sculpture, performance, lighting and sound. Bocanegra synthesizes high and low, familiar and obscure source materials, and draws inspiration from (among other things): a classical ballet, a cult B-film, a modern opera, an out-of-print recruitment guide for the Catholic Sisterhood of the United States, an indie pop diva and her own complicated family history.

Playing dress up, a cautionary tale about nostalgia

The exhibition’s opening scene, perched high up in the 8th floor gallery, is a speculative restaging of the 1789 ballet La Fille mal gardée (the poorly watched girl). Set in an idealized French countryside (for the benefit of urban ballet-goers), La Fille... tells the story of a young farm girl whose powerlessness in choosing a mate is comedically offset by her widowed mother’s inability to monitor her romantic exploits.

Bocanegra interprets this source material through a series of costumes installed on mannequins, which straddle the line between the absurd and the wearable. Collaged together from discarded Metropolitan Ballet costumes, photographs, lengths of twine, synthetic daffodils, sod, tulle, farm equipment, ribbon and any number of other materials, these costumes have a madcap milkmaid quality to them that shows Bocanegra at her most playful and unrestrained.

Accompanying the mannequins, which dot the gallery like scarecrows in a field, is a large wood-framed theatrical backdrop to which Bocanegra has affixed a sparse “field” of wilted flowers made from hand painted and embroidered fabrics. If this all sounds a bit too precious, too removed from the world of contemporary experience to be of use, that’s because it is — at least in and of itself. What “La Fille” establishes is a kind of thematic ground for the rest of the show — introducing girlhood as historically and culturally contingent and pointing to the slippages between a script or score and how a performance sits on a body. It also highlights a key tension in Bocanagra’s practice between a love for the handmade and a healthy mistrust of nostalgia.

Uncanny valley, a poignant re-enactment of vulnerability and failure

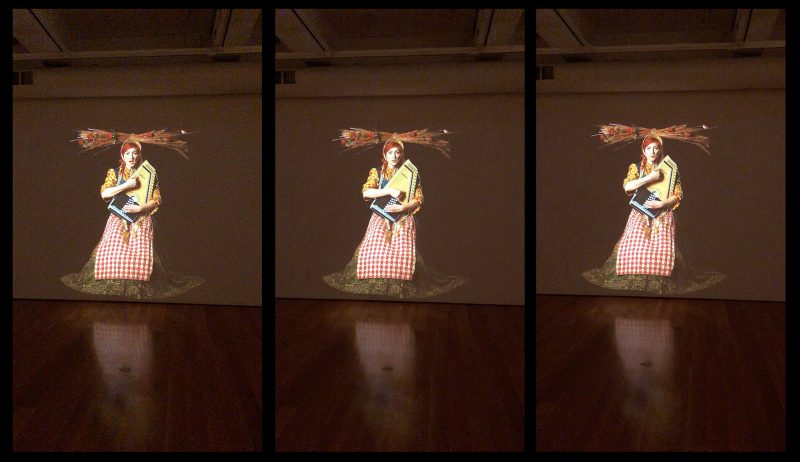

The undeniable highlight of Poorly Watched Girls is “Valley,” a spellbinding video installation which meticulously recreates rarely-seen footage from Judy Garland’s wardrobe test for the 1967 schlock film, Valley of the Dolls (based on the Jacqueline Susann novel of the same title). Though Garland was originally set to appear in the film, which tells the story of aspiring actresses who fall prey to the lure of drugs, her volatility and real-life drug addiction led to her being terminated before shooting even began. Occupying the entire second floor gallery, “Valley” refracts the single surviving wardrobe reel through the prism of Bocanegra’s fertile imagination, enlisting some of the most powerful women in the arts to play the part of the notoriously troubled and fragile Garland. Carrie Mae Weems, Joan Jonas, poet Anne Carson, choreographer Deborah Hay, actor Kate Valk, ballerina Wendy Whelan, singer Alicia Hall Moran and author Tanya Selvaratnam appear in eight perfectly-synched projections which fill the entire space of the gallery (four-to-a-wall) — creating a veritable hall of Judies.

Garland, who was performing on stage from the time she could walk, shot to superstardom at the tender age of 16 playing a pre-pubescent Dorothy Gale in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz — a part for which her body was famously bound and corseted to make it appear less developed. As an adult well into her 30s, she was repeatedly cast in roles that highlighted her childlike qualities, despite the darker realities of her off-camera life.

Appearing in Bocanegra’s “Valley” as an aging Garland anxious to make a showbiz comeback, Weems, Jonas and the others twirl and fidget girlishly in front of the camera in a series of caftans and monochromatic skirt suits.* What comes across in this chorus of gestures is the nervous charisma of the woman behind them — a woman whose compulsion to be seen was yoked to a paralyzing insecurity about being watched. Yet somehow the strength and care that these performers bring to “Valley” grant Garland, at long last, the right kind of attention.

A space for meditation

The first floor is dedicated to two distinct works which offer a meditative conclusion to this ambitious show. “Lemonade, Roses, Satchel,” is a video in which My Brightest Diamond lead singer, Shara Nova appears, in full peasant costume, singing and strumming an autoharp. For this piece, she has turned the fragmented speech patterns of Bocanegra’s own grandmother (who suffered from dementia) into a looped folk song with no distinct verse or chorus.

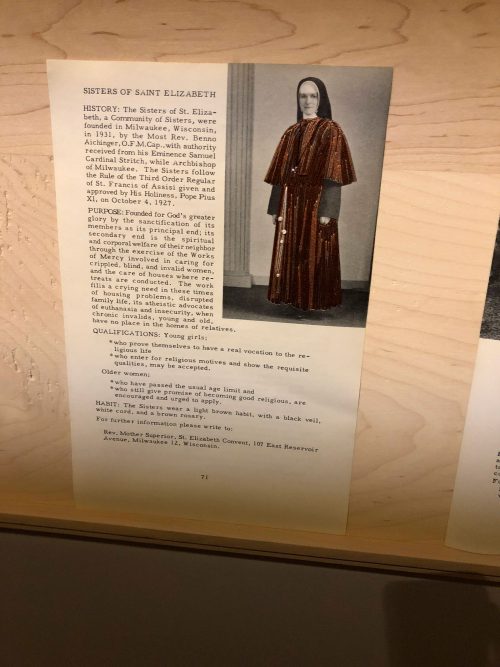

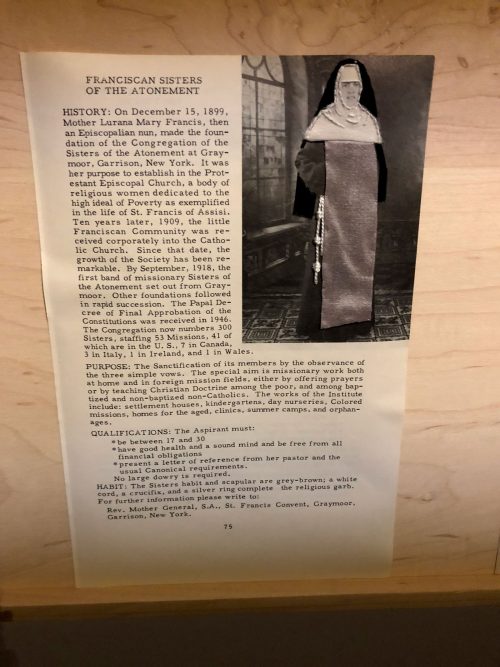

Through a nearby door, in a dimly lit room at the very back of the museum, sits “Dialogue of the Carmelites.” Named for a modern opera in which a convent of nuns is slaughtered by French Revolutionaries, this installation features a disarticulated copy of the 1953 Guide to the the Catholic Sisterhoods in the United States. Each page (comprised of a single image of a nun and a description of the qualifications and duties of her order) has been separated at the spine, hand-embroidered and installed in a row along a single wooden shelf that encircles the gallery. Pages are lit individually from above and at close range such that they appear to glow from within. Strains of an original aria, composed by Bocanegra’s husband, David Lang (Pulitzer Prize winning composer and author of “Symphony for a Broken Orchestra” performed in Philadelphia in 2017), and sung by classical musician Caroline Shaw, waft unobtrusively in the background. In contrast to the grand theatricality of other works in the show, the intimate scale of “Dialogue” calls the viewer into a very private, contemplative experience — one which mirrors the quiet isolation of convent life itself. The youth of the women pictured (most orders at this time only accepted recruits up to the age of 30) is a final reminder of girlhood’s paradoxical role in the maintenance of (even the highest) power.

“Poorly Watched Girls” is on view October 5, 2018 through February 17, 2019 at the Fabric Workshop and Museum. For the full slate of related events, visit the museum website. The Fabric Workshop and Museum is located at 1214 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107; gallery hours are Mon-Fri 10-6 and Sat-Sun 12-6.

*Much of the textile work which appears in Poorly Watched Girls, from the costumes in “Valley” to the embroidered pages of the “Dialogue of the Carmelites” was done by the Fabric Workshop team.

More Photos