A series of brightly colored yet puzzling prints and sculptures are tidily lined up in the white cube of the Project Space at The Delaware Contemporary. Aaron Eliah Terry, who grew up in Philadelphia and recently returned after several years on the West Coast, reassembles album covers, political posters and soundbites into multi-layered screen-prints and sonic Plexiglas installations. His solo exhibition Syncopated Samizdat riffs off the rediscovery of his first records and political advertisements that he acquired as a teenager and which shape his thinking today. Echoing the sonic and literary spirit of Dada, Terry’s imagery brings together the vibe and visual language of reggae and soul, punk, blues, and minimal music, while pondering America’s political and cultural history. Without being nostalgic, his synesthetic collages and assemblages interweave momentous events in Philadelphia’s past with broader questions about truth, power distribution, social justice and humanity.

Seize the time

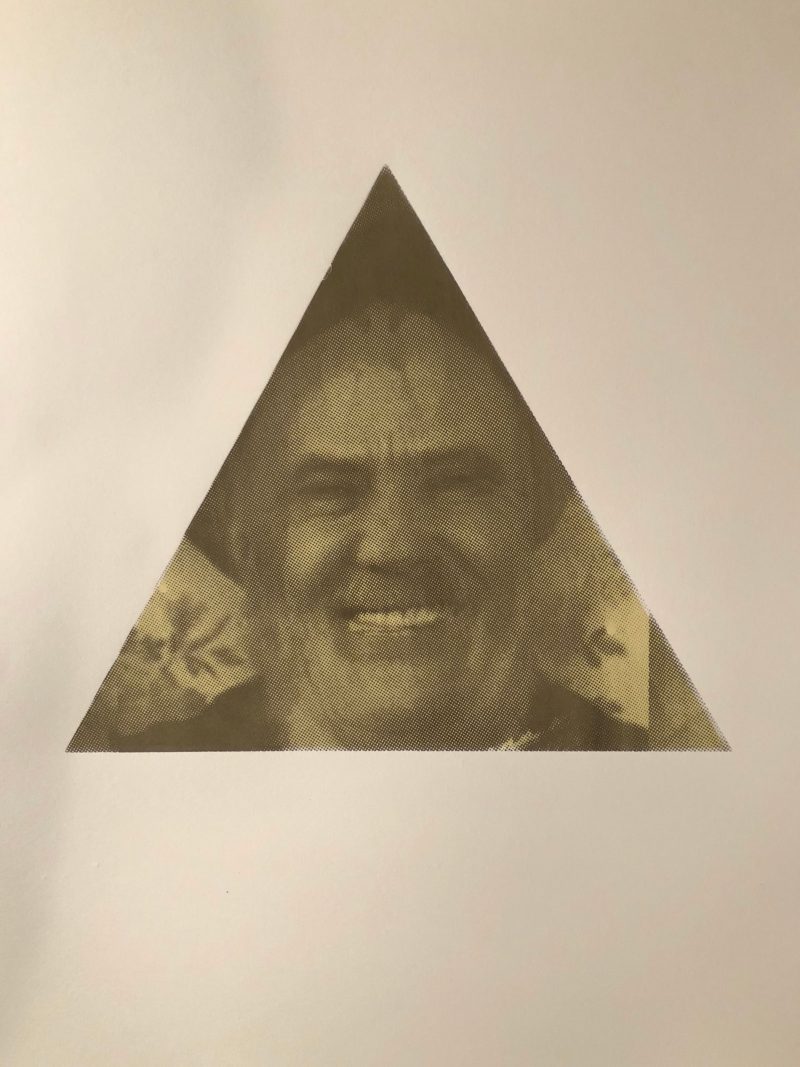

Large letters shout “Seize The Time” from a red and pink pyramidal background. The print nearest the entrance jumps right into American history, quoting former Black Panther Party chairwoman and singer-songwriter Elaine Brown’s 1969 song and album of the same name. This title is surrounded by an assemblage of album art, alternating arches of red, yellow and wood-grain ornamental stripes and more text, including the phrase “Stop the execution!” — which originated from the movement to free local activist, journalist, and MOVE* member, Mumia Abu-Jamal, who was convicted of the murder of a Philadelphia police officer in 1982 (this conviction has been hotly contested by supporters of Abu Jamal). The reproduced record cover, for “Cosa Nuestra” by Willie Colón, shows the trombonist, standing over a body, ironically “armed” with his instrument case.

Like the final verse of Elaine Brown’s song, “‘Cause you do not act / Like those who care / You’ve never even fought / For the liberty you claim to lack,” the combination of slogan, album cover and song lyrics in Terry’s work is a call to action which demands that viewers consider their own willingness to confront injustice. As much as Brown’s lyrics are still meaningful today, Terry has added a side-note near the bottom of the print that is both aspirational and ominous. The words “Live Loving” and “You’re Gonna Get Yours” seem to ask where we stand in the ongoing fight for equality in the US.

A visual revolution

On the opposite side of the entrance, pixelated but still recognizable images of outstretched hands, a fractured cassette tape (simply labelled “soul”), a broken record and a torn record sleeve populate the screen print “Shadow Free.” An enthroned member of the Black Panther party and a series of stylized, running legs frame the entire composition. The graininess of this screen print recalls the sonic and visual ethos of the black musical underground which (like the roots of soul, reggae and black punk) was always closely intertwined with the political activism of the 1960s and ’70s (and for which the textual message urged more than aesthetic concerns). Terry’s metaphorical juxtaposition of the soul and the body reminds us of the people behind political movements who find expression in the language and freedom of visual art and music.

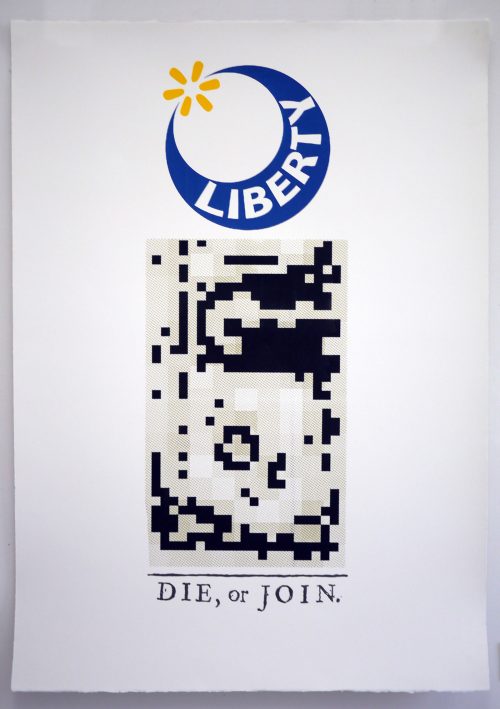

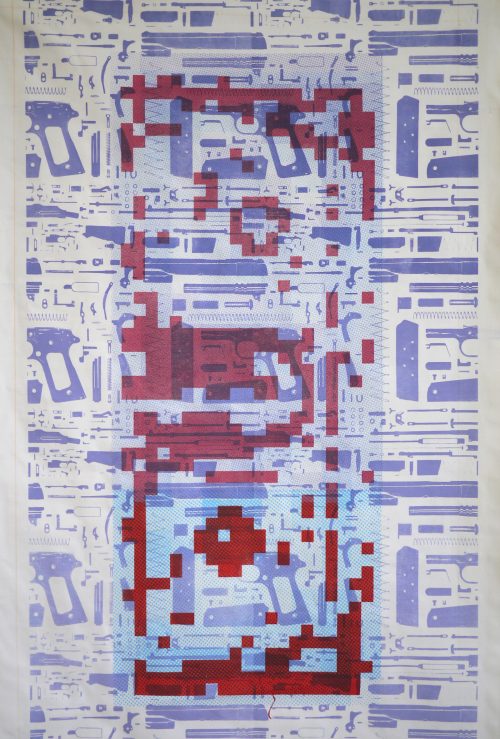

The right to bear arms

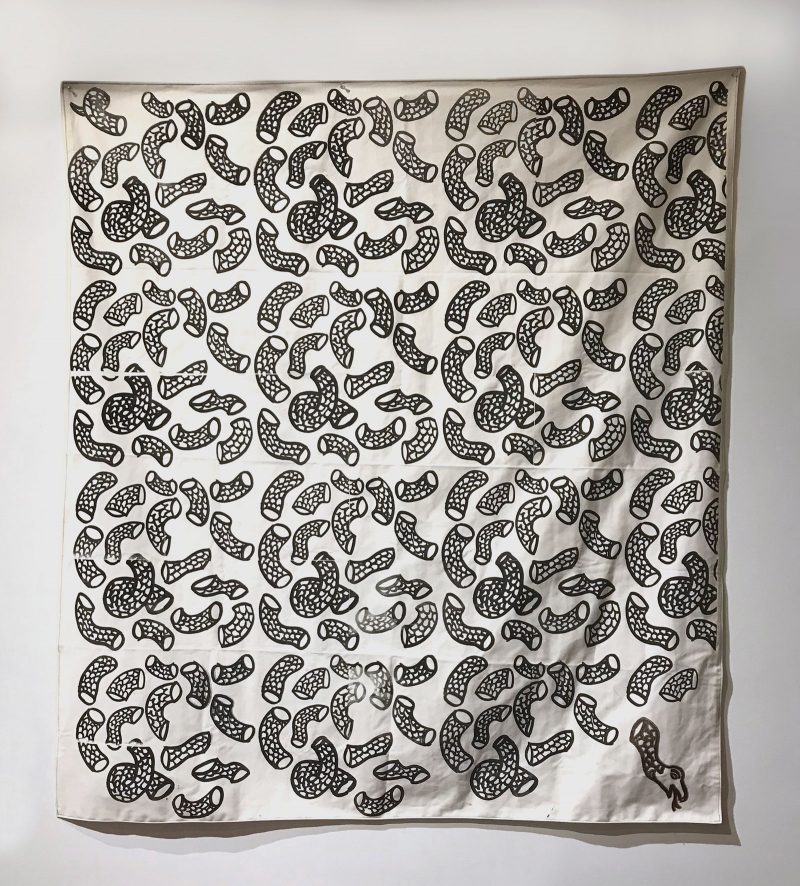

Terry’s prints appear as propositions against inequality that deploy music and verse like metaphorical guns. The motif of the gun recurs in Terry’s screen-print of the instruction manual for a 3-D-printed firearm. Despite being prohibited by US courts, the first downloadable 3-D printed firearm recently became available online for a short period of time. The artist has fractured the essential parts of the gun and laid them out, like a blueprint, in blue and red color on fabric. The fabric seems almost decorative, as if intended for a garment visually stitched together to shelter the human body. But the design unsettles this apparent comfort. The potential ease of producing this killing machine raises questions about the legitimacy of the Second Amendment and the ways it unavoidably redistributes power. Approaching the gun as a tool of human control, Terry seems to ask whether or not the unrestricted right to weapons out-balances our right to freedom of movement and self-determination.

Like fractured witnesses of the past, Aaron Eliah Terry’s screen-prints and sound sculptures revive the Eastern European communist tradition of a “Samizdat,” which utilized hand-copied reproductions of forbidden literature as the mouthpiece of resistance. On first viewing, Terry’s works seem to materialize his adolescent search for truth, justice and guidance. Yet through a process of critical analysis and deep listening into history, his collages and assemblages also ask us to reconsider who we are and what has shaped us along the way. Though the works seem to provide an unvarnished glimpse at the artist’s politics, they directly confront the viewer with their own existential questions: What inspires us? What do we support? What are we willing to do?

“Syncopated Samizdat” by Aaron Eliah Terry runs September 21, 2018 – January 10, 2019 at The Delaware Contemporary, 200 South Madison St., Wilmington, DE 19801. Gallery Hours: Tues 12-5, Wed 12-7, Thurs – Sat 10 – 5, Sun 12 -5, Closed Monday; phone: 302-656-6466

* Read Imani’s interview with theater artist Marc Bamuthi Joseph about Opera Philadelphia’s 2017 production of “We Shall Not Be Moved,” which addresses the history and legacy of the 1985 MOVE bombings.

More Photos