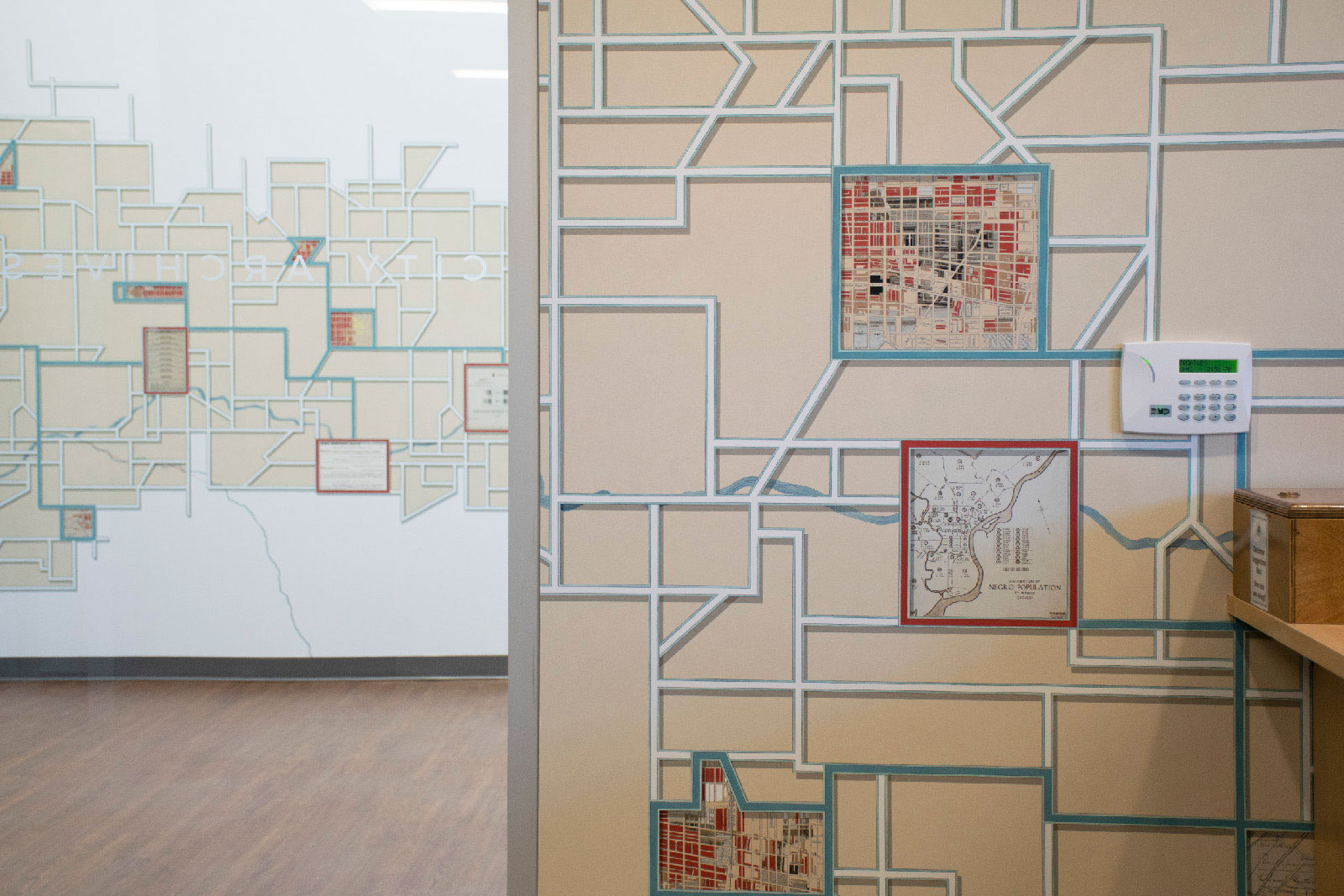

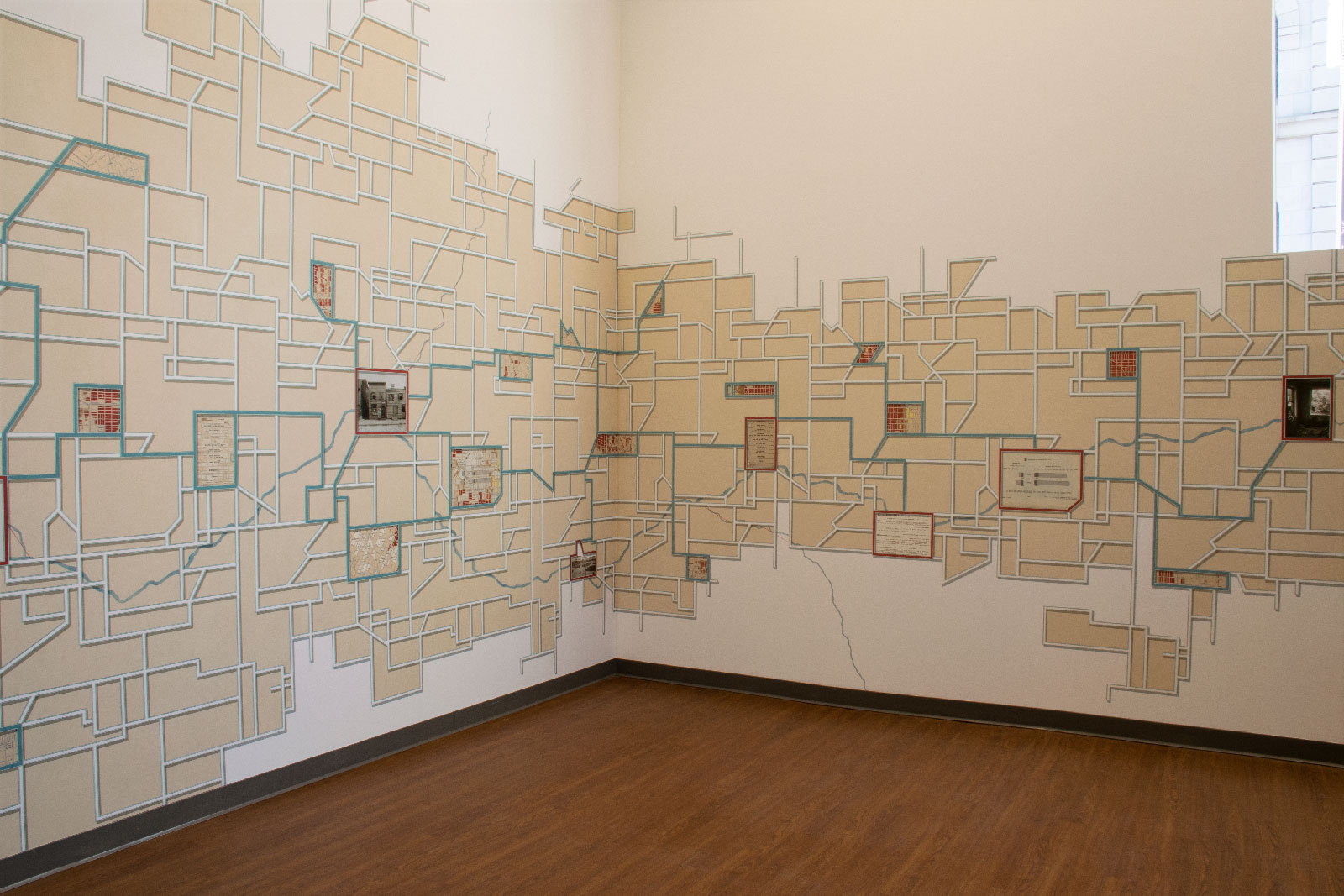

The Philadelphia City Archives sits on the corner of 6th and Spring Garden Streets, next to the Yards Brewery. Artist Talia Eve Greene’s “interactive mural,” Charting a Path to Resistance, occupies the foyer of the building and a long wall in the reading room just beyond the foyer. At first glance, the mural appears to be a grid map of the City. It is “interactive” because the mural, which is painted, digitized, and ultimately printed on wallpaper, includes a series of documents that function as hotspots which can be scanned by computer tablets that the Archives provides. Once scanned, the tablet displays a chapter of information which augments the document embedded in the mural. Each of the chapters relates to the history of African Americans in Philadelphia through the lens of two topics: housing discrimination and slavery.

In fact, the grid that appears to be the backbone of the mural is not literally a redlining map or a map of City grids. Rather, it’s the artist’s “abstract meditation” upon various archival maps she discovered in the Archives, primarily a redlining map in the City’s possession. Redlining, of course, refers to discriminatory practices by which banks, insurance companies, and other institutions including federal and state governments, tracked the racial composition of various neighborhoods and limited the availability of credit in those areas, effectively ensuring the deterioration of housing in those areas. The mural also was inspired by other maps the artist found in the Archives which were related to the evolution of the City’s street grid — for instance, one which tracked the conversion of natural waterways to sewers.

There is an audio feature of the tablets which is set automatically to read the text to the viewer. No headphones are provided for the tablets, so the audio is broadcast in the space. The audio can be disabled, so that you can silently read the text, however, it has to be disabled every time you move to a new chapter. Moreover, when more than one visitor is listening to the text, the audio is quite distracting. [ ED. NOTE: There are headphones to listen quietly to the audio on the tablets. Be sure to ask for them when you get a tablet.]

Although the text presented on the tablets is fascinating, and important, the connections between the text and the mural too often are hard to discern. At some point then, there is an inclination to give up on the mural and sit and read the text.

Narratives documenting discrimination

Narratives, archival documents, and photographs are employed on the tablets to illustrate various, oftentimes institutional, manifestations of discrimination, and to examine the subtle and unexpected ways that the African American community sometimes resisted such discrimination. One important phenomenon addressed is housing discrimination which was fostered, among other things, by redlining. The hotspot on the mural relating to this topic presents a confidential letter, dated January 4, 1944, to the City from a contractor who “recently completed a Racial Map for the City of Philadelphia, showing those blocks on which there exists Colored occupancy.” The City and various private institutions used this type of information to further discriminatory practices related to housing.

Resistance in the African American community

On the resistance side, one chapter on the tablet features a number of lending institutions owned by African Americans which sought to assist African Americans in acquiring property in areas from which they might otherwise have been excluded. There also is a chapter related to the role of now defunct Black newspapers which reported on injustice and poor housing conditions and provided a platform for citizens to express themselves and galvanize community support. In a section on abolition, there is the inspiring tale of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, formed by an interracial group of women who were excluded from leadership roles in the national abolition society. This includes a profile of Sarah Mapps Douglass, who helped to start the Female Literacy Society and went on to become the headmaster of the Institute for Colored Youth (now Cheyney University.) She was a leader in her own right, and also helped to educate a generation of leaders including Octavius Catto.

The effectiveness of the exhibit

While the text included in the project can be reviewed in any order, there is an introductory plaque and an introductory hotspot in the foyer of the Archives, which focuses upon the present day, and, as the visitor moves forward from the foyer through the reading room, the content moves back in time. Unfortunately, this is not explained up front to the viewer, which creates confusion about the organization of the mural. Moreover, many viewers may be overwhelmed with information because the scope of the exhibition is so ambitious and attempts to capture such a broad swath of African American history.*

As noted above, the mural is an “abstract meditation,” whose illustrations are subjective. Unfortunately, because this is not explained to the viewer, it can be bewildering to try to figure out what exactly is being portrayed. The grid-based design is intended to focus upon various themes gleaned from the artist’s research of the maps and other documents housed in the Archives – specifically themes relating to layering, time, networks, and connections, as those themes are reflected in both the natural geography and the development of the City over time. Because of the disconnect between the mural and the text, however, the viewer is not likely to appreciate the richness of these subtleties as they are expressed visually in the mural.

There may, however, be a quick fix to this problem, in the form of clear explanatory information about the exhibit, which could be presented in text on the wall, and to which visitors could be directed before venturing through the exhibit. Indeed, with even a small amount of further explication, the mural itself might come to life in ways that the viewer, confused about what is being portrayed, might otherwise fail to appreciate.

There is no question that the educational value of the content presented through the tablets is enormous. Indeed, the artist has been working with the School District of Philadelphia to develop a curriculum related to the material presented, and to encourage classes to visit the exhibit. Because the mural does not stand on its own, while the content recorded on the tablets does, I wonder whether the project would be more effective in a text-based publication, whether in book form or digitally through a website or blog.

Finally, the question should at least be asked — whether there is something objectionable about a project focused upon African American history in Philadelphia which has been created by a white artist. I don’t think so. In fact, I did not realize that Ms. Greene was white until after I saw the exhibit. I assumed she was African American, and that assumption was directly related to the content presented. I accordingly would be surprised if members of the African American community would find any part of the project objectionable. Indeed, to the contrary.

In addition to the installation images presented here, there is a short YouTube video which documents the project. There also are apps, under the name Resistance: Philadelphia, which include all of the content of the project, and can be downloaded through the Apple app store or through the Google play.

We’ve written about the work of Talia Greene before, most recently about her installation at Glen Foerd on the Delaware. The current exhibition, Charting a Path to Resistance: An interactive mural at the Philadelphia City Archives, was commissioned by the City of Philadelphia’s Percent for Art Program and Department of Records. The Archives are located at 548 Spring Garden Street and the exhibition will be on permanent display at the Archives.

* To give some context to the ambitiousness of the project, the content of the exhibition as presented on the tablets is divided into the following sections: — Early Activism in Philadelphia, the Ganges Africans, Leadership in the Free Black Community, Social Activism and Religion, Vigilance as Resistance, Education as Resistance, The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, 19th Century Violence and Intimidation, Philadelphia and the Underground Railroad, Knowledge is Power, the Great Migration I, 20th Century Violence and Intimidation, Black Banking, Redlining, Poor Housing Conditions Lead to Action, Public Housing, Working within the System, Integrated Neighborhoods, Changing Neighborhoods — 1940 – 1964.