Everyone interested in public art in the U.S. during the 1980s knew the work of Siah Armajani. He lead the field with work that actively questioned what constituted the “public” and how art might best serve it. He didn’t create sculptural objects, but rather sites — some interior, such as his “Louis Kahn Lecture Room” (1982) at Fleisher Art Memorial in South Philadelphia; he also designed buildings, bridges and gardens outdoors. His work involves social interaction with spaces and makes reference to vernacular, American building forms. But he skews those forms so that viewers are forced to think about what they would otherwise perceive as ordinary spaces and everyday interactions within and around them.

If Armajani’s work has received somewhat limited attention within the art world, it is because his most important work has operated outside the gallery/museum network of art for purchase and display. So it is most welcome, as well as timely, that the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) is showing Siah Armajani: Follow This Line at the Met Breuer through June 2. In connection with the exhibition the Public Art Fund has commissioned the re-creation of “Bridge Over Tree” (1970) on the Empire Fulton Ferry Lawn at Brooklyn Bridge Park, where it has a spectacular, river-front site between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges.

Armajani, who was forced to leave Iran because of his political activities in the 1960s, has a wide-ranging interest in both Persian and Western literature and philosophy and in science. He also embodies the immigrant’s view of American culture, where nothing is taken for granted. He brings all of this to his art, resulting in a body of work that lends itself to slow contemplation rather than a view from the distance or in passing. Armajani is interested in complex, ultimately political ideas about social life and how they are variously theorized, enacted, fostered, regulated, limited, prohibited and/or represented. His work is also an ongoing search for the appropriate, artistic means to express complex ideas. It does not provide easy answers, but invites interested viewers to join the artist on the journey.

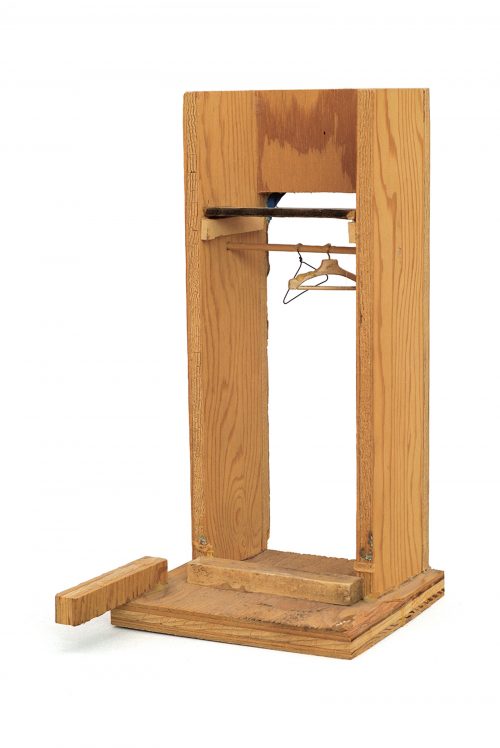

A number of Armajani’s works bear the names of historical figures, many of them involved with utopian projects that failed. He dedicated four reading rooms to the anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti – who were executed as traitors by the U.S. government; they make reference to Alexander Rodchenko’s reading room for a worker’s club, itself reflecting utopian ideas about the place of art in the early Soviet state, ideas which did not last long. The artist has made numerous works that refer to study and the dissemination of knowledge: not only the reading rooms but a study garden, a schoolhouse, bookshelves, books and dictionaries.

The form most associated with Armajani and which he has used most often is the bridge. He has made many bridge maquettes and several have been built. Some function in the manner of conventional bridges, others such as “Bridge Over Tree” are unconnected to separate masses of land – bridges that don’t bridge water or geological fissures. I suspect that bridges interest the artist because they embody the concept of contracts – mutual agreement — which is also necessary for successful social structures. After all, a bridge needs mutual agreement between the parties in charge of the land at both ends.

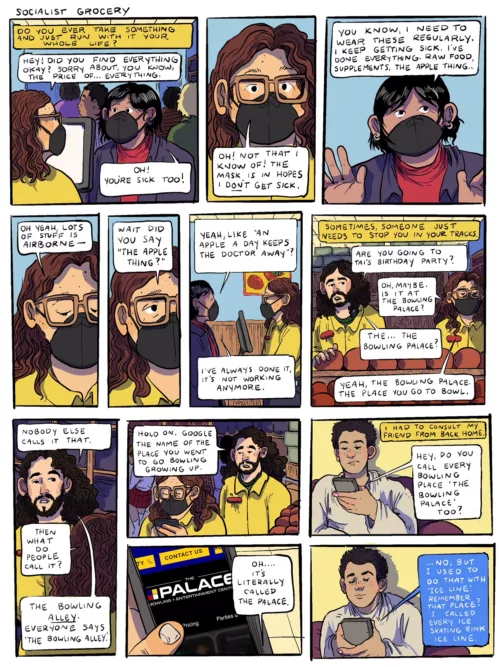

“Moon Landing” (1969), while a singular format, reflects several of Armajani’s recurring themes. It consists of a portable television set and five pages from the New York Times from the day after the U.S. landed a man on the moon; the artist has written over every single letter of the text, as if to absorb it through the act of re-inscribing it. The face of the tv tube bears the text: ”This tv has witnessed the Apollo 11 mission.” The statement goes on to say that it was turned on when the spacecraft took off and turned off eight days later, when the space capsule landed. The artist unplugged the tv set and didn’t use it again.

![Public artist of bridges and space and concerns for community, Siah Armajani at the Met Breuer 4 Siah Armajani (Iranian-American, born Tehran, 1939). Moon Landing [detail], 1969. stenciled television, lock, ink on five double-sided sheets of newspaper. 13 1/2 × 12 1/2 × 9 in. (34.3 × 31.8 × 22.9 cm) television; 23 1/8 × 14 3/16 in. (58.7 × 37.6 cm) one newspaper; 23 1/8 × 29 5/8 in. (58.7 × 75.2 cm) four newspapers. Courtesy the artist and Rossi & Rossi](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/2019/03/Artblog-Siah-Armajani-10-Landing-on-the-Moon-detail-1969-800x624.jpg)

The exhibition includes drawings, collage, paintings, film, sculpture, environments, a large number of maquettes and a slide show of public work. The superb catalog, “Siah Armajani; Follow This Line,” ISBN 9781935963196, was produced by the Walker Art Center, which organized the exhibition with the Met. It is a particularly valuable guide to the development of Armajani’s art in all its diversity. Numerous, clearly-written essays address his origins in Iran and the implications of exile, his interest in scientific developments, film work, use of American building forms and his public projects. It includes texts by the artist and by several younger artists influenced by his work, as well as the usual back matter. The sensitive design by Aryn Beitz supports the artist’s thought process, employing translucent paper so that each page hints at text on its reverse and the following page – yet it is surprisingly readable. Ideas are interconnected, as we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Siah Armajani: Follow This Line is on view at the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10021 until June 2, 2019.

More Photos

× 15 cm). Collection MAMCO, Geneva Courtesy the artist