During a period when U.S. government policies are arousing so much anger, the exhibition Artists Respond: American Artists and the Vietnam War 1965-1975 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (through August 18, then traveling to Minneapolis) is extraordinarily timely. It offers an unprecedented look at fifty-eight artists united only by their opposition to the Vietnam War, which hung over a generation of Americans, particularly those of draftable age. The exhibition should be essential viewing for artists and others interested in political art, for anyone who thinks American art of the period was limited to Pop Art, Minimalism and Conceptualism, and for younger viewers who want insight into how a prior generation responded to turbulent political events. It is a loud rebuke to those who question whether art can mix with politics.

The Vietnam War continues to be contentious among historians, and curator Melissa Ho has done a masterful job, despite her acknowledgment that the subject exceeds the scope of a single exhibition. Some of the artworks have never been previously exhibited. Many other works never received critical attention. Still other works fell out of history because they were anomalous within the artists’ careers. Even the best known pieces, such as Martha Rosler’s “Bringing the War Home” (1967-72), have only recently been widely acknowledged, after decades of neglect.

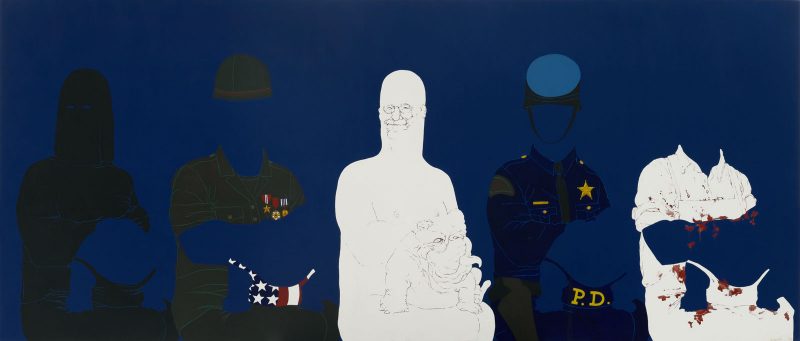

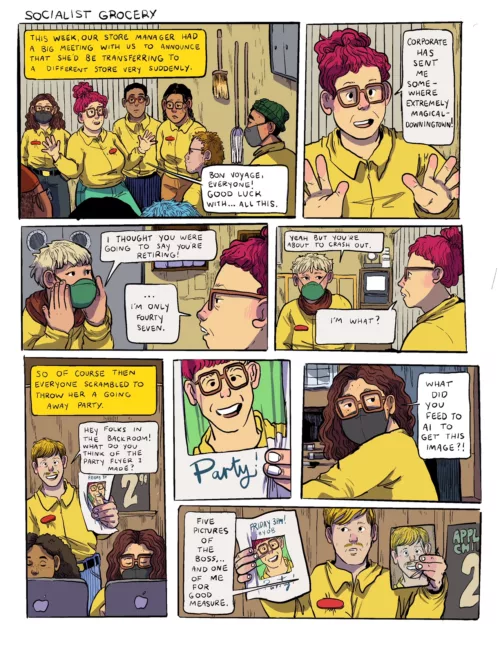

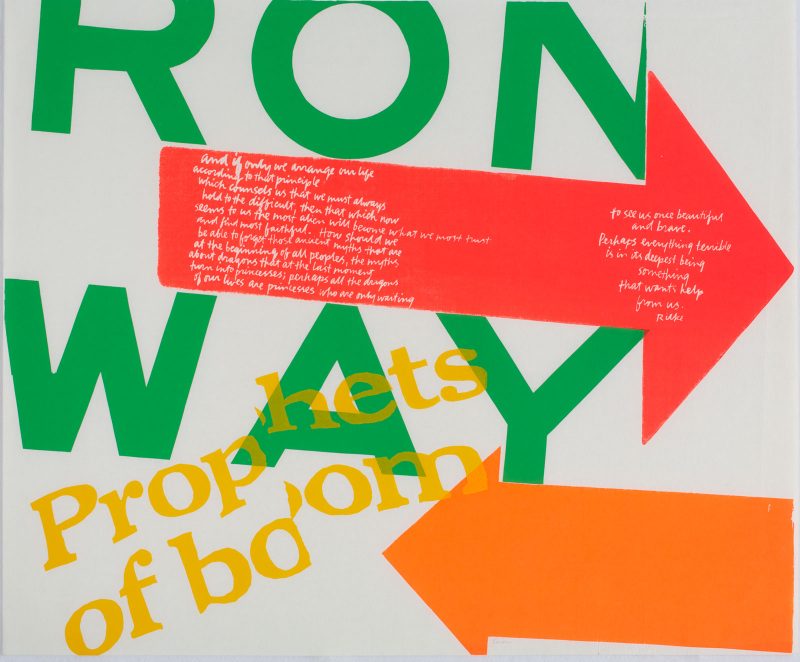

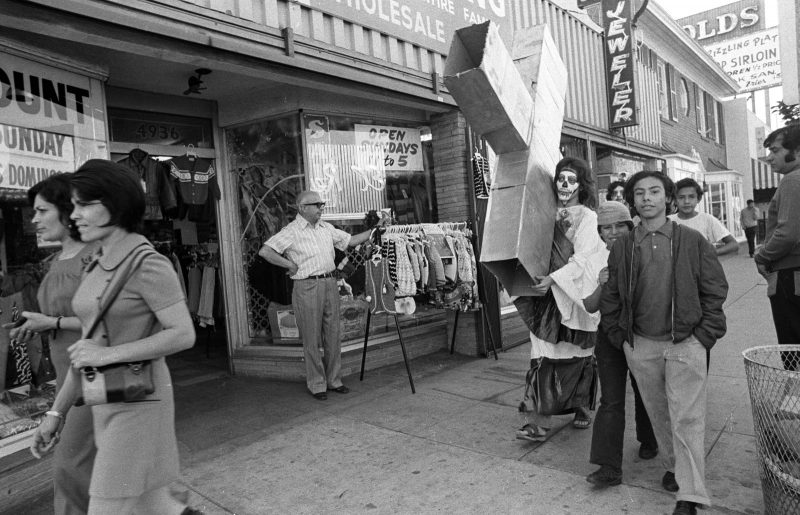

The exhibition covers all possible media: painting, sculpture, drawing, film and video, photography, posters, installations, photo books and numerous types of performance. It is equally diverse as to style, including abstraction, documentary realism, satirical representation and many forms of conceptual practice. Some of the artists and their political works are well known, including Hans Haacke, Martha Rosler, David Hammons and Leon Golub. But much of the art will be new to a museum-going audience for reasons of changing taste, such as screenprints by Corita Kent or the paintings of May Stevens, because of the limited attention given to artists of color such as Mel Casas and Faith Ringgold, as well as the inherent ephemerality of some material, such as posters by Rupert Garcia and street performances by Kim Jones and the Los Angeles collective, Asco.

Some of the artists were veterans – of WWII, Korea and Vietnam. Rupert García, speaking at the symposium following the exhibition opening, acknowledged that he had enlisted in the Vietnam War with enthusiasm and attended art school on the GI Bill; yet he never admitted his military experience to fellow art students who convinced him to join the war protests. García contributed posters for specific political events, while other works in the exhibition were made for benefit exhibitions organized in support of anti-war activities. Still other work, such as Judith Bernstein’s anger-filled paintings inspired by profane graffiti found in men’s restrooms, were entirely personal and unexhibitable at the time.

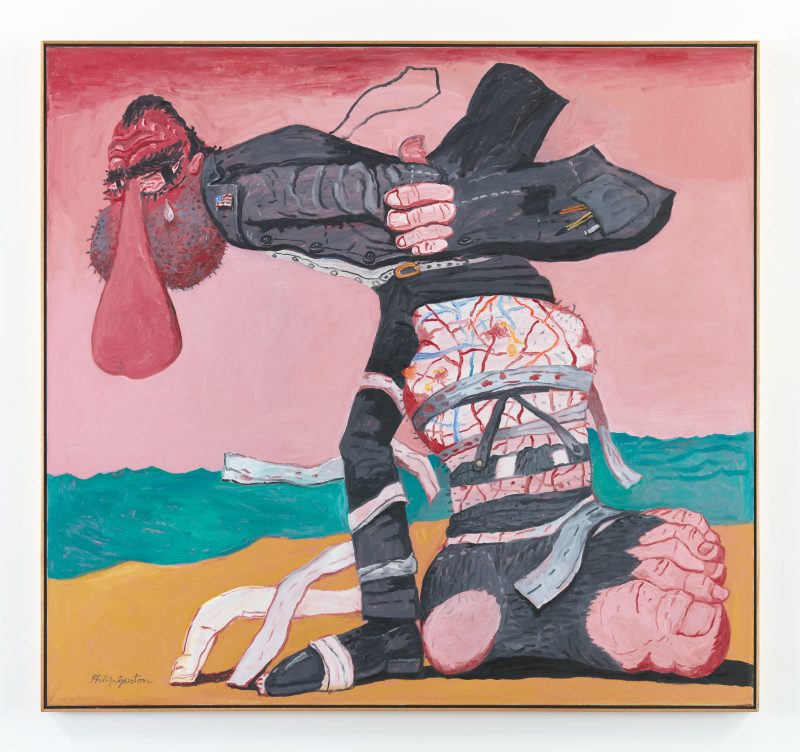

Ho takes a broad view of what constituted a response to the war, including work that made no direct reference to Vietnam or even to war. Among these are works involving danger and/or violence to the body, such as Chris Burden’s “Shoot” (1971), Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece” (1964) and Jim Nutt’s paintings of bound and dismembered bodies.

A substantial portion of the work grew out of the artists’ involvement with various marginalized communities who formed self-empowerment groups, which began with the Black Power movement of the 60s. Black, Chicano and Native American artists were cognizant that their communities contributed disproportionally to the American troops and hence the fatalities; these veterans returned to a country that continued to exclude them. For many of the women, protest of the war was an extension of their feminist activities, something Martha Rosler emphasized during the symposium. The connection is clear in works such as Liliana Porter’s screenprint of a “New York Times” photograph showing a Vietnamese woman with a gun to her head. Below the image Porter has written:“This woman is northvietnamese, southafrican, puertorican, colombian, black, argentinian, my mother, my sister, you, I.”

One subject raised by the exhibition is the suitability of abstraction to political content. Viewers of Dan Flavin’s “monument 4 those who have been killed in ambush (to P.K. who reminded me about death)” (1966) might well miss any war reference unless they pondered the title. But the political content of Barnett Newman’s “Lace curtain for Major Daily” (1968) is clearly conveyed by the use of barbed wire for the otherwise spare and geometric sculpture that rebukes the Chicago mayor who called on National Guard troops to confront antiwar protesters.

Two films by Carolee Schneeman, “Viet Flakes” (1962-67) and “Snows” (1967), are situated in the center of the exhibition and several of the artists who spoke at the symposium emphasized Schneemann’s central influence, as well as her absence – she had died the week before the exhibition’s opening. “Viet Flakes” is based upon newspaper images of the Vietnam War, and was one of several films that Schneemann presented within a kinetic theater performance, “Snows,” that was part of Angry Arts Week (January-February, 1967), an artist’s protest against the war.

The exhibition is accompanied by a particularly heavy and handsome catalog, Melissa Ho, ed., Artists Respond: American Artists and the Vietnam War 1965-1975 (Smithsonian American Art Museum and Princeton University Press, Washington and Princeton: 2019) ISBN 978 0 691 19118 8, that will make a significant contribution long beyond the exhibition. It includes short essays on each of the artists, a chronology of the Vietnam War, an introductory essay by Ho and further essays by Thomas Crow on the anti-war art of a group of California artists as bearing witness, Erica Levin on the relationship of experimental film to the television war coverage, Mignon Nixon on feminist politics in relationship to the war, and Martha Rosler on the relationship between her anti-war protest activity and her art.

“Artists Respond: American Artists and the Vietnam War 1965-1975” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, March 15, 2019 – August 18, 2019.

More Photos