The premise behind Make Room for Me is an ambitious one: highlight the work of queer and femme identifying artists from the Middle/ Near East. The scope of this ambition, however, did not overwhelm curator Sarah Trad. Trad managed to cull the works down to a succinct and challenging bunch – a range that highlights video, installation, photography, performance, and zines – while maintaining the thesis of the show: visibility.

Make Room for Me features 11 artists: Yasmina Hilal, Alia Hijaab, Sholeh Asgary, Minoosh Zomorodinia, Mette Loulou von Kohl, Donia Jarrar, Kris Rumman, Nishat Hossain, Noorann Matties, Samar Ziadat, and Sarah Alfarhan. The works are spread over Little Berlin’s industrial-feeling space, with photographs hung on walls, installations tucked into corners, and videos presented on screens of various sizes and types. This range gives the gallery a freshness as you move through it, and the works are spaced in such a way that you have the required area to inspect and appreciate each artist’s group of works. For a show of this range and theme (the title is, after all, Make Room for Me), this space is essential, and I was excited to see it present. Surprisingly, this contemplative space was even there on the crowded opening night.

I most appreciated this open quality when I spent time with Ahia Hijaab’s video – to me, the star of the exhibition. “Al Ghorba” (2018, 6:07) is presented on a very small screen, with a single set of headphones. This creates an intimate experience between viewer and video. The brief artwork tells a story of a woman moving from Syria to an unknown Western city (perhaps inspired by the artist’s own journey from Syria to Vancouver). It is a beautifully animated video, composed of vibrant colors that bring the illustrations to vivid life. The hypnotic voiceover gives a great sense of rhythm to the work for those of us who do not know Arabic (the words are also illustrated on-screen), and, I would assume the voice is comforting still to those who do. The video tells a familiar story of moving away from home and family, but of course has the added layer of the anxiety of international moving, guilt of leaving one’s loved-ones, and anxiety regarding the safety of the home nation. Ultimately, the work is a moving and thought-provoking story of immigration and family, delivered in an elegant and visually satisfying package.

Across the gallery, Minoosh Zomorodinia’s videos (“Sensation III” and “Resist”) are similarly compelling. “Sensation III” takes a more meditative bent, showing someone on a hilltop, their figure covered with a silver heat blanket held against their body by the wind. There is a kind of sublimeness to the work: the covered person is only identifiable as a woman by the faint outline of breasts beneath the blanket; she is alone with the wind. Importantly, the heat blanket is also commonly known as an “emergency blanket” or “survival blanket” – nomenclature which adds a layer to the work by reemphasizing the solitude and vulnerability of the female body in this open space. It is quite meditative to experience, and leaves you with an imagined sense of the wind blowing against your own (gendered) body.

Nearby, a selection of photographs from Nooran Matties cannot help but attract viewers. They have a grungy feel about them, as though the camera lens was dusty, or the photos were developed under imperfect circumstances. This patina is alluring, and, coupled with the focus on banality (applying makeup, bending over, a sleeve of tattoos…), is enchanting. Perhaps the exposed quality of the works is what is so reminiscent of another female photographer, Deana Lawson. I was particularly drawn to the vulnerability of “Untitled III,” which depicts the artist bending over, hair hanging toward the floor, back and neck exposed, all set within a clothing-cluttered room. The relatability of the image is fantastic – viewers may imagine themselves in their own rooms, drying their hair after a shower, a connection made all the easier by the lack of a face.

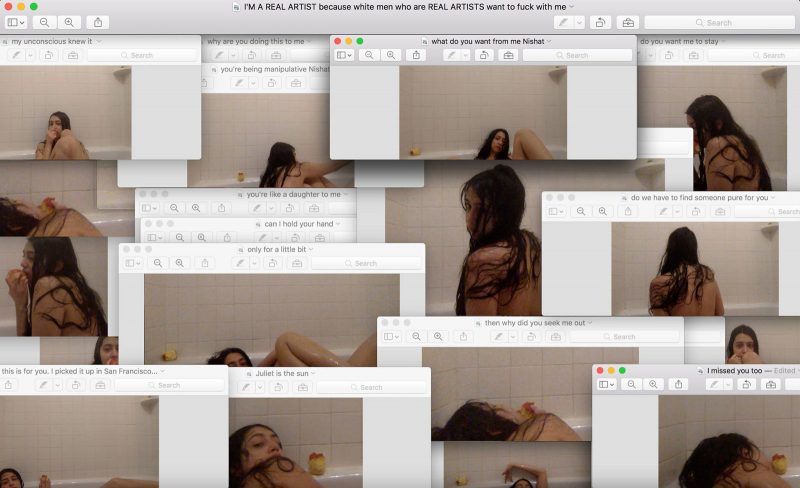

This facelessness was a common theme in the show, running across the works of Zomorodinia, Matties, Asgary, Rumman, and – at times – the performance from von Kohl. In such an identity-focused show, this was an interesting choice. Perhaps the idea was to make the works relatable, or to comment on the loss of individuality that comes with stereotypes of gender and exoticism. Regardless, it is an effective choice that still gets at the overarching idea of vulnerability. Of course some works broke this mold, such as the screenshots made of layered photos from Nishat Hossain, which feature her face repeatedly.

The performance by Mette Loulou von Kohl (at the opening on June 8) straddled this facial in/visibility. In “No one likes an ugly revolutionary,” the artist transitioned between covering and uncovering her face in a punchy performance that was both poetic and balletic, urgent and reflective. In her exploration of generational storytelling, identity formation, and the sexualization of brown female bodies (such as Palestinian plane hijacker Leila Khaled, and others) von Kohl delivered an energy that left the audience silent at the end of the performance. It was unclear whether this silence was due to anticipation or digestion – or, most likely, a mix of both. This thoughtfulness characterizes the show as a whole, an exhibition which demands a slow pace and thoughtful consumption, and rewards those who undergo this process.

“Make Room for Me,” Little Berlin, June 8 – 29, 2019

Note: Little Berlin Gallery is only open on Sundays from noon to 4 PM

More Photos