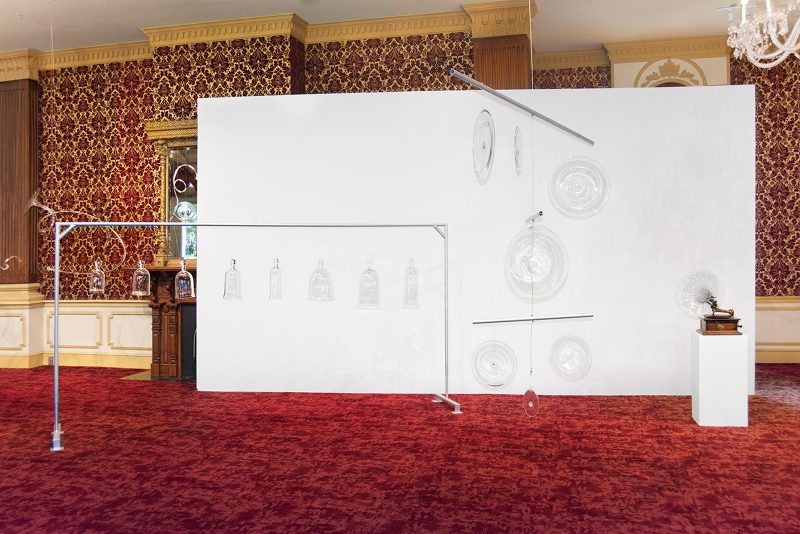

“Phantom Frequencies,” a visual-art installation and mini-opera by performance-artist Martha McDonald and composer and musician Laura Baird, activates the vast and boldly decorated entrance lobby of Wheaton Art Center’s Museum of American Glass in Millville, NJ. The piece, with blown glass plates and bell-jars dangling from ropes attached to armatures, sits atop the lobby’s plush red carpeting and serves as a gateway to Emanation 2019, the Center’s third biennial exhibition, up through December, 2019.

The artists invited to exhibit by independent curator Julie Courtney—Jesse Krimes, Tristin Lowe, Karyn Olivier, Richard Torchia, Allan Wexler, Jo Yarrington, along with McDonald and Baird—drew inspiration for their site-specific works from Wheaton’s permanent collection of thousands of works in glass made over centuries, and made use of the Center’s remarkable resources: a working glassmaking studio and its master glassmakers.

The museum’s lobby packs a visual wallop. Seventy feet wide, 40 feet deep, and 15 feet high, it’s 42,000 cubic-feet of flocked wallpaper dizzyingly patterned in deepest gold and claret, red wall-to-wall carpeting with a swirling texture, chandeliers with octopus arms from which countless crystal beads dangle…and much, much more. The lobby is meant to evoke a Victorian parlor circa 1888—the year Wheaton Industries, which grew into an international maker of glassware, was founded—but its aesthetic speaks strongly of the late 1960s and ‘70s, when the faux-Victorian Wheaton Village was conceived and built.

This mash-up of 19th- and 20th-century decorative excess wasn’t the only anachronism that struck McDonald, who recalls, “As soon as I walked in, I was like, ‘This is a Victorian parlor, but it’s really a brothel.’” Both parlor and brothel echo in the independent yet intertwined interior and oratorio imagined by McDonald and Baird and realized with the help of Wheaton’s glass masters. Hands-on costume-making has been central to McDonald’s practice since its beginnings in the 1990s. For Phantom Frequencies’ costumes, she explains, “I wanted to play up the intimacy of the parlor. With all of the red in the space at Wheaton—it’s a pretty sassy parlor…more of a bordello. So, I thought, ‘Let’s wear undergarments.’”

For their adventures in Wheaton’s wonderland, McDonald and Baird traverse Phantom Frequencies’ dreamscape in corset-shaped “chemises” and wide-legged, below-the-knee “drawers” with a flaring shape that, suitably, suggests vintage ‘70s culottes. Typically made in white or otherwise neutral cotton, McDonald’s chemises and drawers are made in satin and in shades inspired by the peacock feathers prized by Victorians and the era’s riotous use of colors, made possible by newly discovered aniline dyes.

Appearing in her parlor in underwear would have been beyond unimaginable for a “proper” lady of that era. The parlor was a semi-public space in a private home where the family presented their best, most cultured and refined selves—complemented by their finest furnishings, art, and objects, including musical instruments—to visitors. Are McDonald and Baird’s characters improper, then? “There’s a suggestion that we’re ‘women of ill-repute,’” McDonald acknowledges, “but we don’t care! We’re making our own music and we’re going to own it.”

McDonald begins the performance of “Phantom Frequencies” by cranking the handle of a gramophone to set spinning a recording of the song “I Found a Rose in the Devil’s Garden.”* Both the gramophone and the record were found in Wheaton’s attic. The lyrics are contrary to “Phantom Frequencies’” celebration of autonomous womanhood; they are the patronizing words of a man describing how he “saved” a vulnerable young woman from the perils of the big city:

I found a rose, in the devil’s garden

Wand’ring alone, little lonesome rose…

Playing the game, of the Moth and Flame

Beneath the powder and paint,

Maybe the heart of a saint

This moment is bittersweet, for the gramophone struck the death-knell for “parlor-music,” specifically, and family-style, homemade music-making, generally. Baird and McDonald reclaim music-making from the mechanized Victrola in a way Baird describes as “really simple and kind of ritualistic”—creating ringing tones by running their fingers round the tops of wine-glasses and singing lyrics inspired by Carl Sandburg’s 1904 essay “Millville”:

Day and night, fires burn both red and bright. Fires burn and bid the sand let in the light.

Wheaton’s lobby is the antithesis of a white-cube gallery space. That, along with the strength of McDonald and Baird’s vision, allows it to read as a home’s parlor despite the complete absence of furniture. With its wood case, the gramophone is closest to a piece of domestic furnishing. But McDonald and Baird have transformed even it into something both spectral and futuristic by recreating its sound-horn in glass. The contrast between the worn wood case and the gleaming glass is arresting in a steampunky way, as is a similarly solid and transparent ukulele played by Baird.

A characteristically Victorian shelf of bric-a-brac is reimagined supersized and bearing horns of varying shapes made in glass. A mobile holds glass horns—which Baird toots—elegantly stretched and contorted into curlicue shapes as long as 14 feet, inspired by the “whimsies” created by glassmakers in their downtime.

A squat, pillowy cone hanging on wire from the ceiling holds the supporting structure for a hoop-skirt: a series of rings that increase in size as they go from waist-height to floor, suspended on sturdy strips of fabric. From each hoop hang dozens of glass vials identical to those in which were packaged the cure-all “Dr. Wheaton’s Wafers for the Blood, Carbuncles and Other Gatherings.” In a movement titled “Fever Dream” with lyrics inspired by advertisements for the wafers—Monkshood, mercury, foxglove, strychnine tree, you’ll feel fantastic, homeopathic, quality remedies—McDonald proceeds to dance across the exhibition, releasing trickles as well as cascades of tones from the click-clacking vials. She has created and is “playing” a garment as art-object-as-musical-instrument.

A video recording of McDonald and Baird’s performance in and of “Phantom Frequencies” plays on continuous loop on a monitor in the installation. Live and on video, their characters fascinate but don’t play to the audience. They make music for themselves and one another, sharing knowing glances and affectionate smiles. “It’s very much like people are observing us,” Baird says. “In the field of psychoacoustics,” Baird explains, “a ‘phantom frequency’ is a pitch that is perceived while not actually being physically present.” McDonald and Baird’s shared “phantom frequency” is a study, display, and meditation on the alchemical nature—transforming and transformative—of glass, music, and friendship.

*Willie Raskin and Fred Fisher, 1921.

McDonald and Baird will perform Phantom Frequencies live in November (date and time to be determined). Visit wheatonarts.org.