Author’s Preface: On the side of an unassuming suburban road in southwest Philly’s Eastwick neighborhood lies the haunting shell of one of the city’s most impressive examples of Brutalist-style architecture, the former George Wharton Pepper Middle School. As part of this year’s Jane’s Walk, I attended the Pondering Utopia tour at Pepper Middle School, led by Director and Managing Editor of Philadelphia’s Hidden City, Michael Bixler, along with partner Kate Bixler. As we walked around the massive concrete institute, covered in graffiti with memoirs of teenage angst and artistic liberties, we pondered the fate of this now-decaying structure and fantasized about its next life as an urban agriculture center, a daycare, a market space, and even a recreation center. The possibilities were limited only to our imagination, but the reality is the fate of George Wharton Pepper Middle School seems grim. Sinking into a high-risk floodplain in a community that has suffered from ongoing environmental and socioeconomic conflict, the decaying structure is plagued with significant water damage and asbestos. I was glad to experience the story of George Wharton Pepper Middle School before it is gone forever.

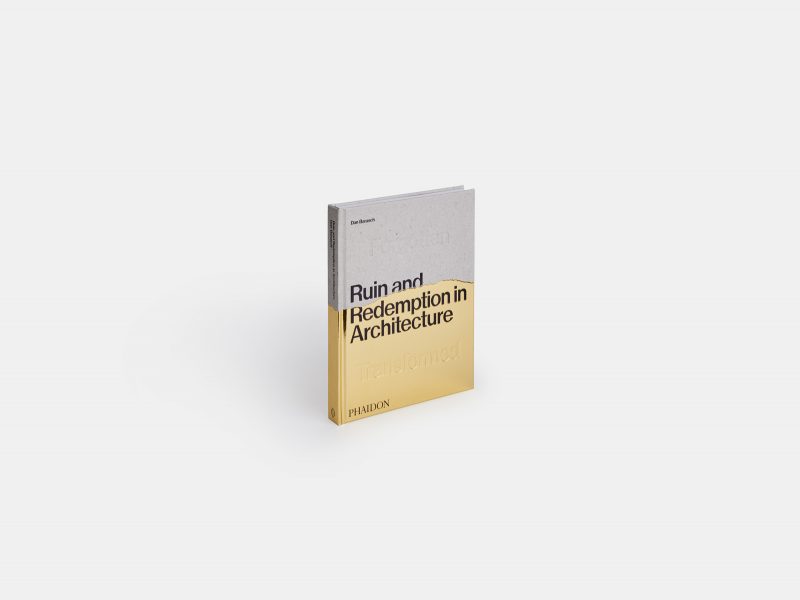

In his book, Ruin and Redemption in Architecture, Dan Barasch memorializes the triumphant revival and often inevitable casualty of once neglected structures like George Pepper. In 240 pages of rich imagery, prefaced by historical accounts and personal experiences, Barasch catalogs international examples of “Lost,” “Reimagined,” “Forgotten,” and “Transformed” architecture. Although heavily visual, this coffee table book alludes to controversial topics related to ownership, permanence, and preservation of the built environment through relevant discussion on gentrification, economics, and social equity. The captivating cover represents the book’s structured dichotomy of old/new and before/after through a juxtaposition of material: a matte, natural fibrous material ghosted with the words “Forgotten” on the front and “Lost” on the back, has been seemingly ripped away to reveal the new, a lustrous gold imprinted with the words “Transformed”, flipped to read “Reimagined.”

A foreword written by Dylan Thuras, writer and co-founder of Atlas Obscura – arguably one of the greatest resources for discovering the world’s zaniest hidden gems – shares a nostalgic account of his first love, an abandoned Flour Mill along the Mississippi River. It is an affinity that many of us share. Perhaps, it’s the thrill of trespassing in the unknown, the unexpected beauty in decay, or the exciting prospect of what could be that lures us to these structures.

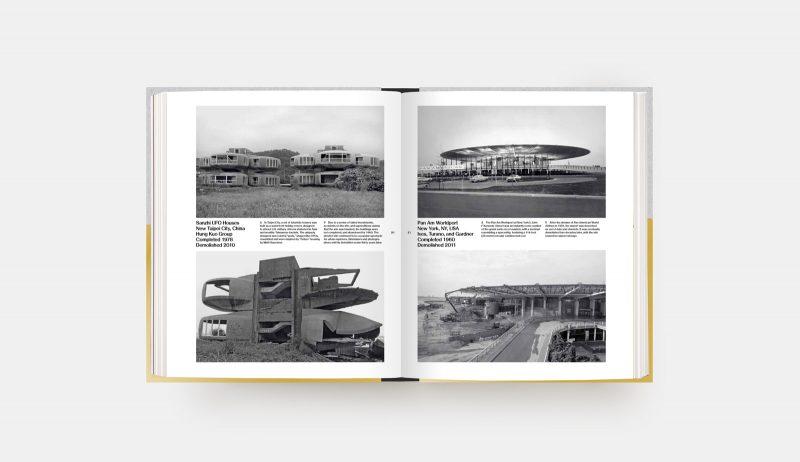

The first chapter, “Lost,” pays poetic homage to structures that fell victim to the wrecking ball due to socio-economic pressures or debatable urban renewal ambitions. Barasch quotes Joni Mitchell’s lyrics “don’t know what you got till it’s gone,” referencing the collective emotional, cultural, and social connections that we have with these structures. In the mix are the obvious “what the hell were they thinking!?” projects: the failed government housing, Pruitt-Igoe, in St. Louis, but also a few questionable demolitions like the former Singer Building in New York (one of the first masonry skyscrapers) that was replaced by a sleeker glass tower. Imagine the architectural significance and beauty that would be lost on Penn’s campus if Denise Scott Brown did not lead the defense of the Fisher Fine Arts Library from modernist demolition?

Brutalist architecture is arguably the most historically detested style and thus prone to destruction to make way for something “better.” The Gettysburg Cyclorama, designed by renowned Architect Richard Neutra in 1962, is a featured casualty. I remember visiting the battlefield during the Cyclorama’s demolition in 2013 and standing among a pile of concrete rubbish with wiry rebar sticking out from the structure. Deemed “a distraction from the integrity” of the battlefield’s surrounding nature, the iconic building was replaced by a new visitor’s center in true Disneyland fashion, mimicking a 19th-century farm.

The chapter “Forgotten” emphasizes the element of time, and the impact of evolving major events such as war, transportation advances, the Olympics, and industry. Sharing a two-page spread with Detroit’s iconic Michigan Central Station is Philly’s Beaux-Arts style PECO Delaware Station, a memorable backdrop to Penn Treaty Park on the Delaware River. Through the patina, these relics tell historical stories of tragedy, victory, and progress; they become part of our collective memory.

“It is up to us to discover the narrative of a deserted building’s past, and up to us to imagine – or even determine- its future.” Dan Barasch

Monochrome photos in these chapters offer alluring glimpses into the often-inaccessible structures, transitioning to vivid and colorful renderings in the subsequent “Reimagined” and “Transformed” chapters, more optimistic and lofty chapters of the book. “Reimagined” highlights ambitious proposals for once abandoned structures, with entrancing before and after images of building facelifts – a glass-wrapped former German war bunker given life as an office building, the concrete banks of the Los Angeles River proposed as a lush recreational park, and a former Italian distillery transformed into an epic beer garden and micro-brewery.

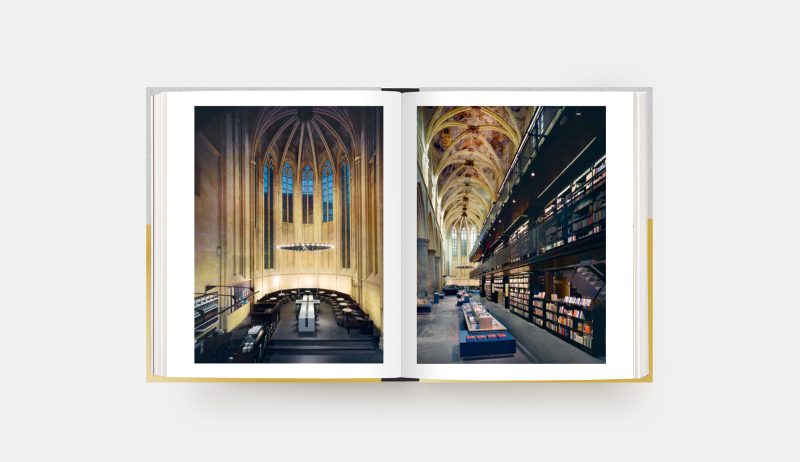

Projects that push the boundaries through a complete reinvention of form and function are noted in the “Transformed” chapter. A series of heterotopias – a former cathedral turned bookstore, steel foundry turned museum, cylindrical gasholders turned apartments – inspire us with creativity. Focusing heavily on the trend to reuse redundant infrastructure as public space, Barasch acknowledges the economic, technical, and political challenges of realizing such revival projects, citing his involvement working on the Lowline project, which seeks to transform an abandoned trolley terminal in New York’s Lower East Side, into a lush subterranean park and recreation space.

The inevitable phenomena of change is integral to the book’s context and has rightfully been a topic of ongoing debate. Barasch dances around the inescapable topic of gentrification, acknowledging the appropriation of abandoned and distraught urban space as a byproduct of urban renewal. How can we transform urban blight but ensure equitable growth? Who should get to decide what stays and what goes? There is no single straightforward answer, but as Barasch rightfully notes, the success of projects is contributed to a democratic development process that emphasizes community and resident contributions, with collaborative private-public partnerships. Particularly in legacy cities with a surplus of post-industrial remnants, such as Philadelphia, these structures, big and small, give our communities authenticity and identity – be it the former breweries of Brewerytown or the textile mills of Manayunk. Their mere existence signifies a feat of survival as ongoing conflicts between socio-historical significance and the demands of profit-driven cookie-cutter real estate development continue to rise. What would Kensington be without its iconic Harbisons Milk Bottle, LOVE park without its flying saucer, or Philadelphia without the Liberty Bell for that matter?

Barasch’s Ruin and Redemption fills us with both hope and trepidation on the future of our evolving built environment, reminding us that the built environment is our collective responsibility. We must keep fighting the good fight.

Ruin and Redemption in Architecture by Dan Barasch: 240 pages, 310 color and black & white illustrations, 81⁄8 × 10 5⁄8 inches, double-sided hardback cover, $60, published by Phaidon. Publication date: March 2019. Also available on Amazon