What artwork by Bill Viola do you remember first experiencing, or which was the first that really moved you?

This was the question that opened “Curators in Conversation: Bill Viola” at the Barnes Foundation on Tuesday July 16. During the 90-minute program, Nancy Ireson, deputy director for collections and exhibitions & Gund Family Chief Curator at the Barnes; Susan Talbott, executive director of the Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM); and Jodi Throckmorton, curator of contemporary art at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), each gave their answer to this question, using it as a way to open a dialogue about Viola’s life and the major themes of his work. The curators each named very different projects as that which most moved them. Ireson, for example, picked Viola’s 2014 video installation “Martyrs” at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Talbott spoke at length about “The Reflecting Pool” – a video from the late-70s that centers on a pool in a wooded area.

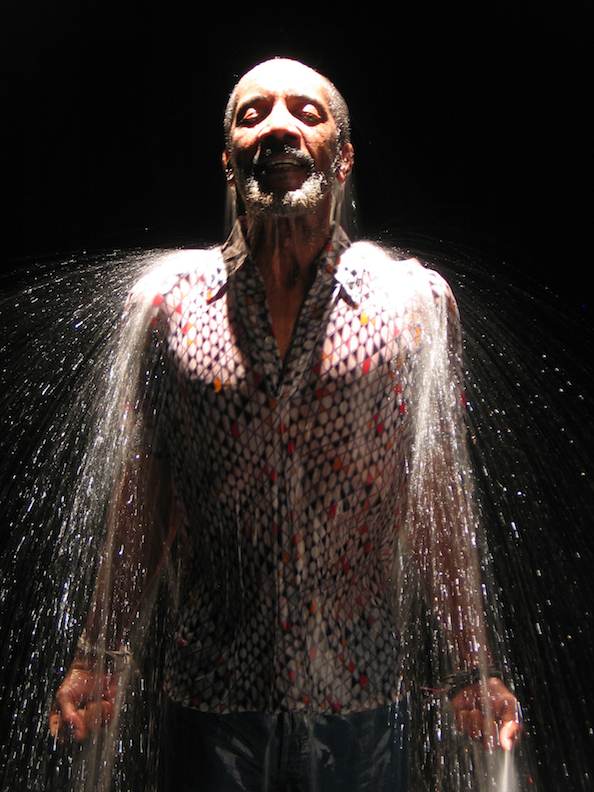

The water element of “The Reflecting Pool” alludes to a formative childhood experience: at age 6, Viola nearly drowned – he was saved at the last moment by his uncle who retrieved him from the bottom of a lake. This experience is echoed in “Ascension” – one of Viola’s most well-known works, on view at the Barnes as part of I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like. “Ascension” is, in fact, another important work for Talbott, as she has purchased it for two different institutions over the course of her esteemed career.

Many of Viola’s artworks feature water, and they often have a spirituality about them – whether because of a sense of the sublime, or through references to religion or religious art. At its core, Viola’s work is about human emotion and liminality: the space in-between, the thread separating life and death, the illusion of solidity or liquidness, the distinction of sacred versus mundane – and how people respond to each of these pairs. These themes are evident in work on view at all three panelist’s institutions this season. As Ireson put it, it is a summer of “Bill Viola in [Philadelphia] like never before.” This gave the curators plenty to discuss.

In her comments, Ireson (Barnes) often highlighted her position as a curator who does not deal with contemporary art. She spoke to the way Viola’s work echoes religious art, like in his 1995 video “The Greeting,” currently on view at the Barnes. Throckmorton (PAFA) was interested in the humanness, the diversity of Viola’s actors in his videos, and the universality of the emotions that he explores. Talbott’s interests (FWM) tied these together, as she spoke to the materiality of Viola. As an artist who works primarily in video installation, suggesting that his work has materiality was an interesting take. However, it was not an unfounded perspective. At the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Talbott is currently featuring “The Veiling” – a work created in partnership with the FWM that is projected onto and through 9 hanging pieces of fabric. Discussion of this piece and its “thingness” opened the conversation in an interesting way, and perhaps alluded once again to the liminality of Bill Viola: object or experience? Both.

The curators each talked about the installation process, and the challenges of displaying video art – especially considering how much technology has changed in the last 30 years. This led to audience questions about the preservation of video, and the concept of “originality” in new media – a rabbit hole that deserves a panel of its own. The curators applauded how the large videos have an immersive quality; and Throckmorton appreciated how Viola encourages viewers to engage with their emotions without intellectualizing the experience – something which art institutions can always use reminders of. The Barnes setting for Viola’s work also made people consider the value of mixing contemporary art with works from other places and times, and how the juxtaposition can illuminate art in new and exciting ways.

The final point made was one brought on by an attendee’s question about the “theatricality of the experience” of looking at Viola’s art. The curators considered the darkened gallery space, seating arrangement, and the viewer’s absorption in the work of art – comparing it to a meditative experience as much as a theatrical one. Ultimately, Talbott summed up the evening nicely, saying that the art of Bill Viola goes beyond theatricality or objecthood, providing a transcendent experience.

Transcendent would certainly capture the feeling that I get when I think of the work that, for me, answers the night’s central question: What artwork by Bill Viola do you remember first experiencing, or which was the first that really moved you? It was December of 2013, at the Conciergerie in Paris. Bill Viola’s 1995 installation “Hall of Whispers” was the first artwork in À Triple Tour, a show made up of 50 works from the collection of François Pinault. I remember walking down the dark hallway lined with videos of people with gags in their mouths and their eyes closed. I am still haunted by the sound of the actors whispering through their restraints. When I returned home after that trip, I began my journey into new media and installation, leading – I believe – to my current position in a contemporary art museum.

Does a claim that Bill Viola’s art is transcendent seem radical on the part of these curators? Perhaps. But for me, at least, it rings absolutely true.

“Curators in Conversation: Bill Viola” took place on July 16 from 6-7:30 pm at the Barnes

I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like

The Barnes Foundation

Until September 15, 2019

Bill Viola: The Veiling

The Fabric Workshop and Museum

June 26 – October 6, 2019

Bill Viola: Ocean Without a Shore

PAFA

June 28 – December 31, 2019