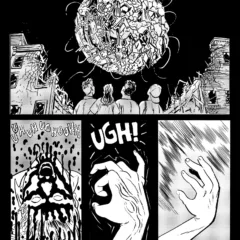

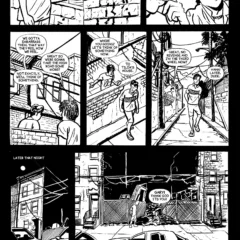

As the lights dimmed and shadows wrapped around the audience for Scribe Video Center’s showing of Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, imbuing the small venue with a sense of immersion, the perfect setting was cast for the strange images that make up the core of the film. Directed by Xavier Neal-Burgin, and co-written by Danielle Burrows and Ashlee Blackwell, the later of whom was in attendance, Horror Noire tells the story of the African-American experience in horror films with a rare, lively depth. The documentary’s framing device saw former genre actors and directors seated in a movie theater discussing not only their roles in iconic horror films, but the genre and cinema in general and its impact on the black presence in Hollywood. Among the interviewees were Rachel True (The Craft), Ernest R Dickerson (dir. Tales From the Crypt: Demon Knight, episodes of The Walking Dead), and Tony Todd (Candyman), along with scholars and genre aficionados like sci-fi and horror/fantasy writer Tananarive Due, the founders of archival site blackhorrormovies.com, and Robin R Means Coleman, the author of the book Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present, a tome that the documentary is based on.

Horror Noire’s biggest success as a documentary is its ability to draw correlation between monumental shifts in what is perceived as the progression of black life in the United States (and often the West in general) and what was shown — or not shown — on movie screens. The film starts with an examination of Birth of a Nation, a film regarded as the first full-length cinematic feature, positing that Birth— with its depiction of the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic and necessary force against encroaching black liberation, with its use of blackface in lieu of an actual African-American actor to play the lascivious “villain”– is, in fact a horror film: it shows the abject horror white Americans felt towards people of color, and that black people gaining autonomy and empowered humanity could mean that white people were losing theirs.

The film winds through the precipitous journey of horror’s dodgy, racialized past, the genre’s trajectory often mirroring the lives of black people in the social sphere. The discussion of Night of the Living Dead leads several of the subjects to ponder if director George Romero, en route to his producers’ office with the film in cans in the trunk of his car and hearing the news of Martin Luther King’s assassination over the radio “knew what he had”– a prescient document of a horror film finished days earlier, a film whose black heroic lead actor defends a small community against ghoulish zombies only to be mistaken for one and killed by an all-white hunting party.

It’s no secret that, despite the seeming glut of horror-esque films of the blaxploitation era, that as the genre grew, black people were reduced to on-screen cannon fodder. Horror Noire’s thoughtful ruminations don’t simply stop at the tried and true tropes like “the black guy always dies first” however. Horror Noire takes its time and pulls its analysis from a rich well of different types of horror and the way those horror films negatively treat black people — as servants, as background characters; as characters like Scatman Crother’s Halloran in The Shining — who seem to exist as magic props for the white hero. Horror Noire also gives space to discuss films that highlight black heroics in films like Eve’s Bayou, Attack the Block, and People Under the Stairs. There’s a deep, rich love for the genre in Horror Noire, and it’s fun seeing actors fondly remember their contributions to the genre. It’s this enthusiasm that speaks to the need for Black people to not only be seen as heroes, but as vulnerable, as witness to strange phenomena and even as victims of emotional crisis, or as Blackwell put it during the Q&A, “characters who are human, whole and muti-dimensional.” Black people want the fantasy of being scared, even when African-American realities often provide true, lived horrors — what better way to imagine oneself as empowered to withstand and triumph despite those horrors?

And of course, there is considerable screen-time given to Get Out, with director Jordan Peele giving generously to a documentary already replete with black horror cognoscenti. Get Out’s place in the horror narrative seems to be as important signifier with regard to black participation and visibility. It’s a film whose politics and allegory speak, finally, to the black experience and not to white fears. The documentary sees Peele’s film as a culmination of both the lived paranoia that being black in America can conjure, as well as a glorious return to heroic roles for black people in genre film, where the stories of people of color are centered and not relegated to the background.

The Q&A provided a platform for Blackwell to discuss not only her involvement in the film, but some of the conclusions she’s come to about horror inclusion in general. Blackwell implored audiences and by proxy producers and directors to “mine spaces that look at other artists’ work,” further stating that “you’ll hear no all the time” but that “we should come together and support, even if Blumhouse says “no”, keep pushing.”

[Ed. Note: Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror is now available to stream at Shudder, and elsewhere online.]

More Photos