The conventional wisdom about art in America is that New York is where the art gets made, and then it’s sold in California—in places like Los Angeles. The City of Angels is a city with a large population of wealthy art collectors and a rich cultural history of its own that has never included a particular school or coterie of defining visual artists. Perhaps in response to Los Angeles’s lack of specific painting tradition, Narrative Painting in Los Angeles, currently on view in Santa Monica’s Craig Krull Gallery, aims to shine a light on local contemporary artists whose work chronicles the particularities and peculiarities of the city I still call home.

Narrative Painting in Los Angeles could be categorized as a show of history, allegory, and personal mythos, although many works fit into more than one of those categories. While the compositions are largely grounded in reality, there are welcome deviations from the purely literal as well. Figurative artists usually, although not always, paint narrative works (or, maybe better said, narrative painters are usually figure painters). There is a long tradition of narrative figurative painting in art’s history. The exhibition text points to the Italian tradition of history painting of, for example, the 15th Century Genovese artist and architect Leon Battista, and suggests that tradition is reflected in the paintings of real-life moments in Los Angeles history appearing in this exhibit.

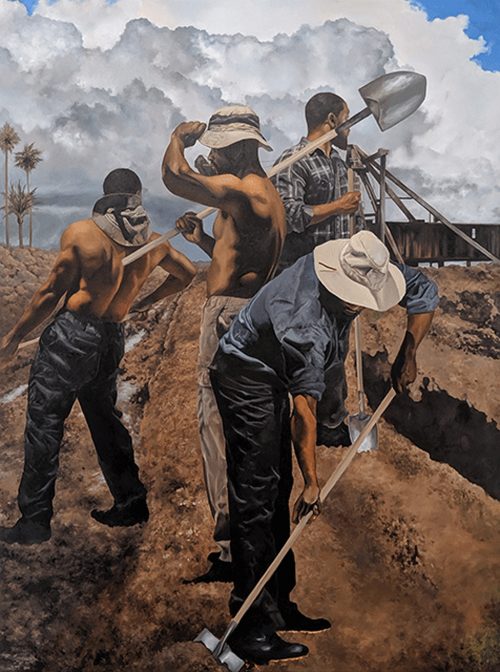

Shawn Michael Warren pays tribute to the black workers who built the famous canals of Venice, California in “Abbot’s Waterway,” where a group of men at work in construction is depicted in monumental fashion against a brilliant blue-and-white sky. Warren marries the grandeur of Diego Rivera’s Social Realist subjects with a George Bellows-esque of appreciation of labor and muscled male bodies.

I did not know that the neighborhood that houses the Venice Canals was racially segregated in 1910 when the Venice Canals were dug, thus these men were employed in creating a paradise they would never be allowed to inhabit. Most significantly, then, there is a deliberate distance created between viewer and the subjects of the painting, all of whom resolutely refuse to engage the spectator’s gaze with eye contact.

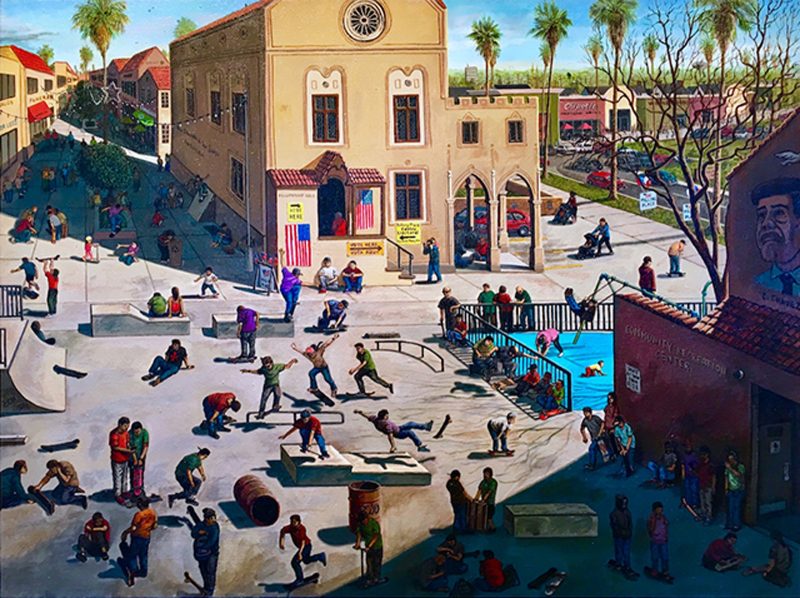

And while the title does a lot of the historically-specific heavy lifting, Sandow Birk’s “The Mid-Term Elections (Skate Park),” it’s easy to imagine Birk’s Dutch-influenced aerial view of town square marked with both polling place signs and children playing was based on something the artist himself observed. The work seems to have elements of both real life and the allegorical: the focus of the individuals in the work is not necessarily on voting, but on their own activities and one another, arguably downplaying the monumental task of democracy–particularly tense on election day in 2018.

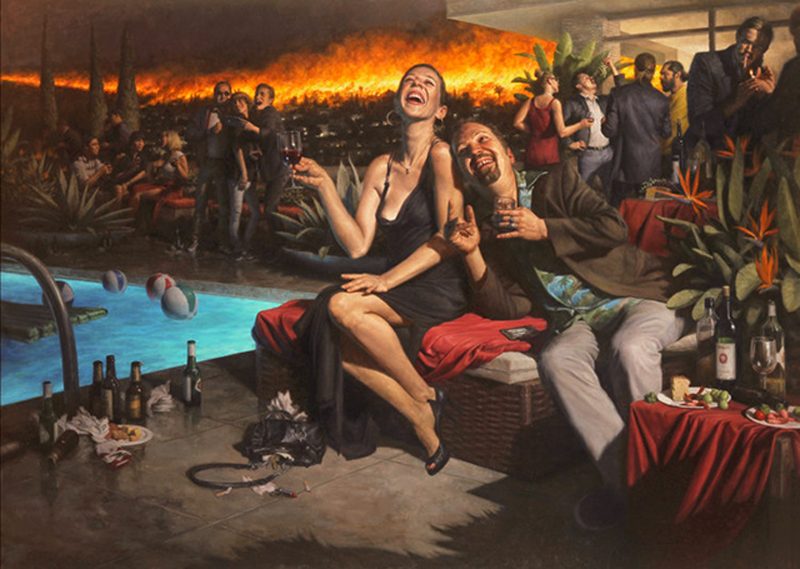

One of the standout works in Narrative Painting in Los Angeles embraces obvious apocalyptic allegory and comes away better for it, despite its eye-rolling kitsch and obvious preachiness. There is nothing subtle about Carl Dobsky’s “Birds of Paradise,” a large-scale painting that is immediately arresting and rewards patient looking. The artist, working in a realistic style, has crafted a Bonfire of the Vanities for the Beverly Hills set: a group of fancy partygoers cavort poolside while a wildfire rages in the background. It’s quite exciting to pick apart the painting and identify the nods to classic art historical themes: there are traces of vanitas still life painting in one corner, where a jumble of grapes and shellfish sits beside a glasses and bottles of wine, theatrically illuminated for purely dramatic effect. The occupants of this painting drink, smoke, and laugh, either blithely ignoring the deadly fire slicing across the black sky or (perhaps more likely), knowing that it won’t touch them. Indeed, several of the figures in the background are depicted taking a selfie with the fire behind them. Even if their fancy hillside mansion burns down, they will always be able to relocate and rebuild and begin the same cycle all over again.

The moral judgement we as the audience are encouraged to render to the occupants of “Birds of Paradise” is clear, raising a fascinating conundrum: this work is on display in a commercial gallery in Los Angeles. Ostensibly, it is for sale, and will likely be sold to someone with the disposable income to buy such a large painting, so do the figures in their hillside estate tittering and partying as the world burns down also represent the inevitable buyer(s) of “Birds of Paradise?” If so, what a neat trick for Carl Dobsky.

Meanwhile, several works draw upon the artist’s own psyche in exploration of larger social issues, all of which can be interpreted to have especially salient messages in Los Angeles. Ja’Rie Gray’s several lovely paintings are all forms of self-portrait: two small-scale head-and-shoulders images, and one large work in which she paints herself three times, seated in a single space like a group portrait. In the two small portraits form the diptych “What if I Was…?” two Ja’Ries face one another, dressed in identical shirts and headscarves, but in the work on the left, Ja’Rie Gray has painted herself with her skin drastically lightened, imagining what she would look like with a skin color deemed more desirable and societally valuable. While it’s not explicitly discussed here, it’s easy to connect Gray’s paintings with issues of colorism and beauty standards to Los Angeles and Hollywood, where people of color with darker skin tones continue to face struggles in casting to this day.

In a similar vein, Lola Gil’s paintings on display are also personal and deeply symbolic, using the motifs of masks and cameras to indict Los Angeles’s camera-ready, artificially smiley atmosphere. Her thoroughly creepy style can best be described as Mexican surrealist painter Leonora Carrington (1917-2011)-meets-Balthus (1907-2001), painter of erotically-charged narratives involving young girls. In “The Memory Room,” Gil depicts a female figure riding on the back of a male figure, in an interior setting, both holding cameras, as a cabinet of faces leers around the corner.

And while it doesn’t depict any sort of human figure explicitly, James Doolin’s “Highway Patrol” also has an emotional, human-centered point of entry. Painted in flat, smooth strokes from the point of view of a driver on an endless road of red and white car lights, “Highway Patrol’s” mood is melancholy, aptly capturing the stultifying loneliness of hours spent in traffic on the 405 Freeway, hoping against hope that you’ll get somewhere you want to be.

If your only associations with Los Angeles involve Hollywood and palm trees, Narrative Painting in Los Angeles will provide a welcome corrective. Narrowing its focus to one category, figurative painting, the show expertly displays a wide range of concerns and approaches. The good and the bad of the city and its history are on display; every work is authentically, indisputably grounded in the often painful love many of us Angelenos feel for our city.

Narrative Painting in Los Angeles, Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, CA, July 20 – August 31, 2019