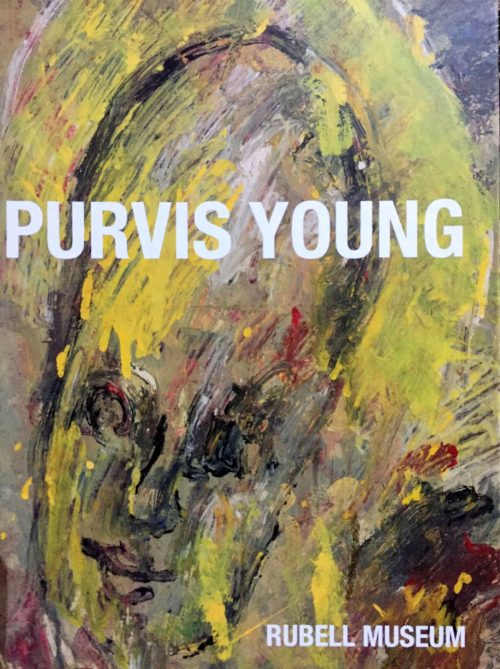

Purvis Young (Rubell Family Collection/Contemporary Arts Foundation, Miami: 2018) ISBN 978-0-9911770-5-9

This handsome and copiously-illustrated survey of the paintings of Purvis Young (1943-2010) will be an excellent introduction for readers who don’t know his work as well as a useful resource for those who do. His subjects reflected the life around him in Overtown, an historically-Black neighborhood of Miami and his work was created from materials scavenged from the streets and donated by neighbors and supporters. Young’s art grew out of protest, and he developed a distinctive personal style to depict drug use, refugees, insect infestation, slavery and political demonstrations, as well as a group of subjects to which he attached personal, allegorical meaning, such as pregnant women, horses and angels.

Young had a singular career for a self-trained artist in that his work circulated within his own, inner-city neighborhood as well as in the larger art world, where he had gallery and museum exhibitions as well as several public commissions. His large output included paintings and books – often abandoned ledgers – into which he pasted his own drawings. Several years before the artist’s death the Rubell Family Collection/Contemporary Arts Foundation purchased the large quantity of work the artist had retained. It has worked to catalog it, disseminate it to other museums, and to make it more broadly known. This catalog to an exhibition is an excellent means of doing so. It includes an interview with Hans Ulbrich Obrist that addresses Young’s artistic development and influences, critical essays by Gean Moreno and Franklin Sirmans, essays by early supporters who witnessed and contributed to the artist’s self-education and development and a selected exhibition history and list of public collections that own his work.

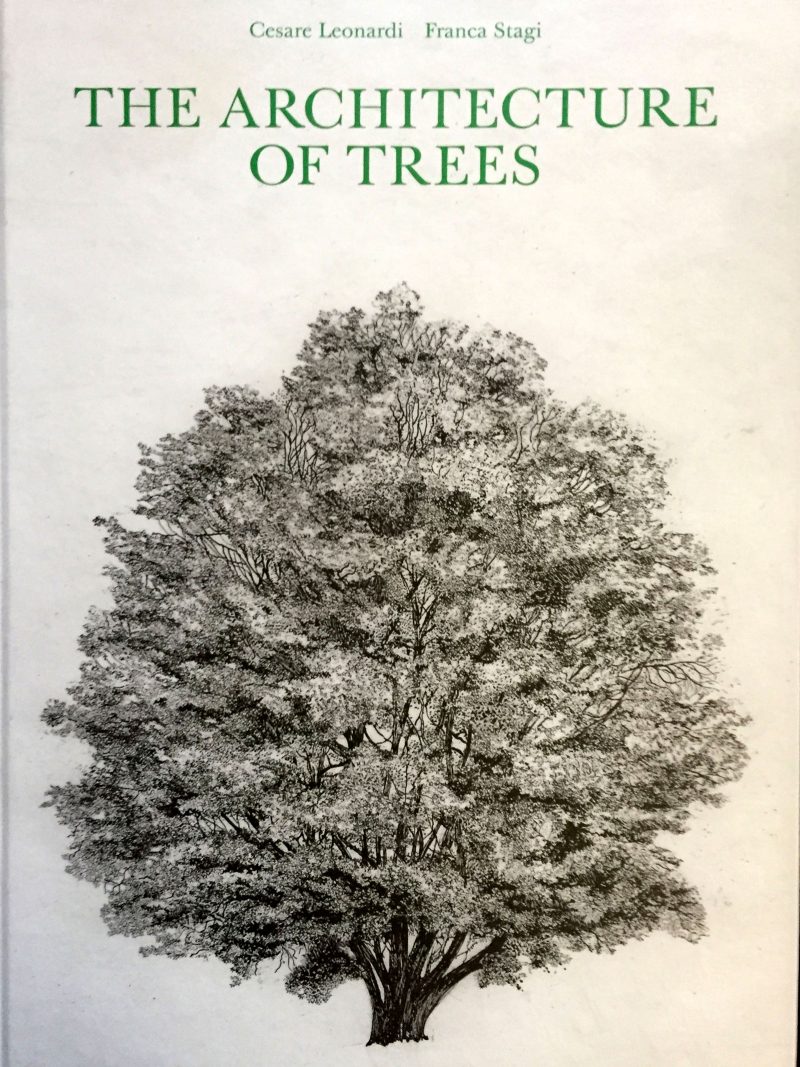

Cesare Lombardi and Franca Stagi The Architecture of Trees (Princeton Architectural Press, New York: 2019) ISBN 987-1-61689-806-9

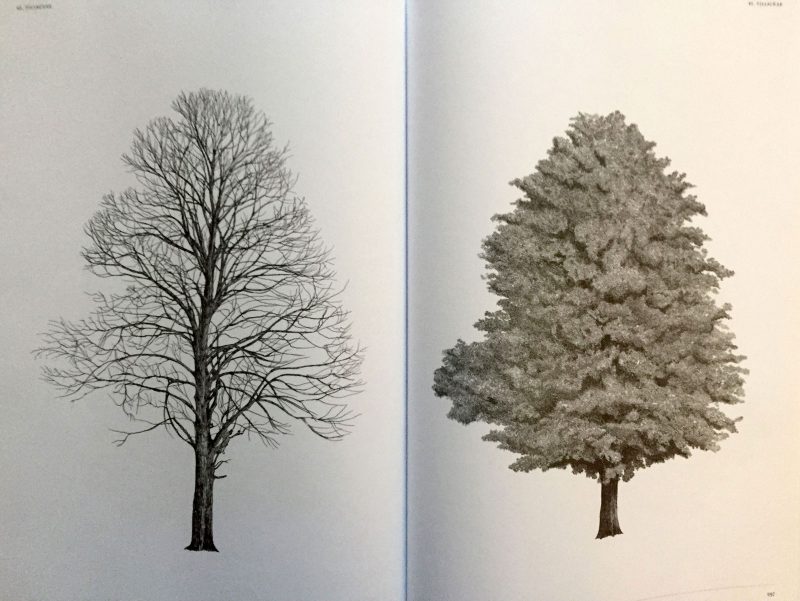

This giant and beautifully-produced book illustrating the structure of 212 tree species will appeal to fanciers of detailed, representational drawing as well as to horticulturalists and landscape designers, for whom it was written. It is the first English edition of an Italian classic from 1982 by two architect/designers with a particular interest in urbanism. It was intended to be a practical guide for would-be designers of parks, which Lombardi and Stagi thought should be designed to the scale of trees, and was described as a “labor of love and obsession.”

The drawings celebrate the beauty and abundance of natural forms, and artists may want to put the volume on the shelf besides Darcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1917) as a source of design inspiration. The illustrations of deciduous trees include them with leaves and with bare branches, with further details of seeds, cones, fruit, flowers and leaves, analyses of the shade which trees cast and charts of their colors over the seasons. The book also includes Stagi’s writing on the significance of urban trees, articles on the history of botanical illustration, and appendixes of everything from the era in which trees were introduced into Europe to the etymology of genera, as well as a bibliography.

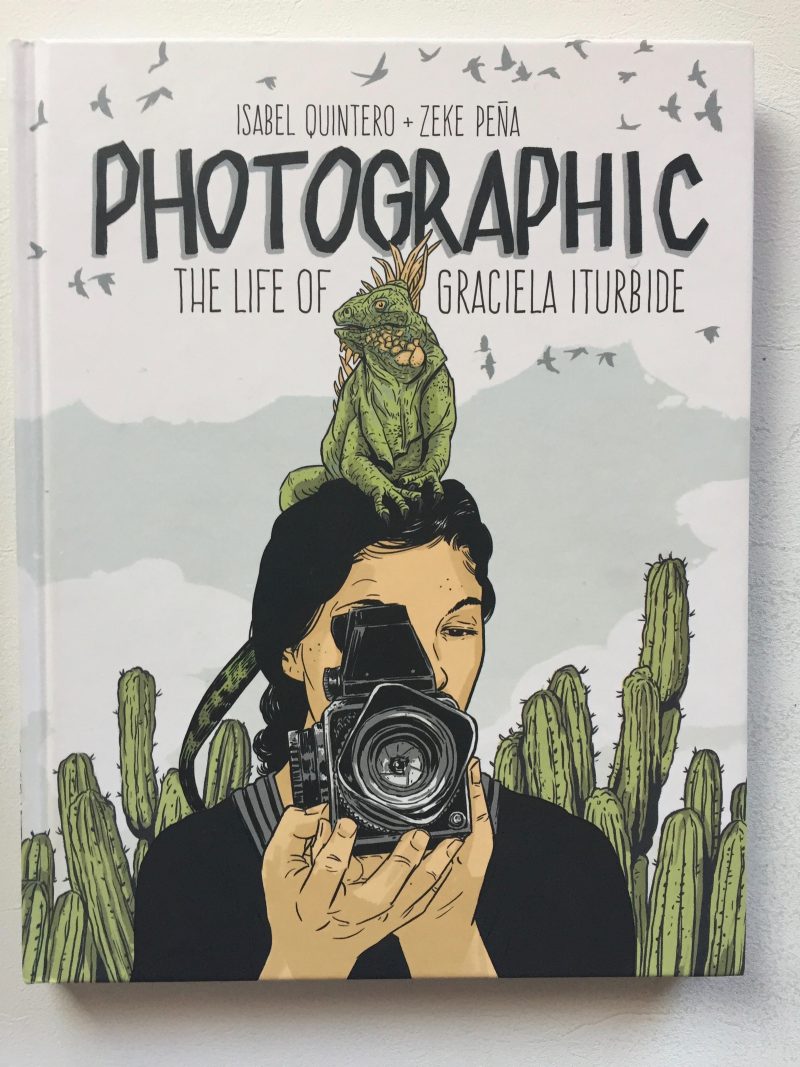

Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña, “Photographic; The Life of Graciela Iturbide” (Getty Publications, Los Angeles: 2018) ISBN 978-1-947440-00-5

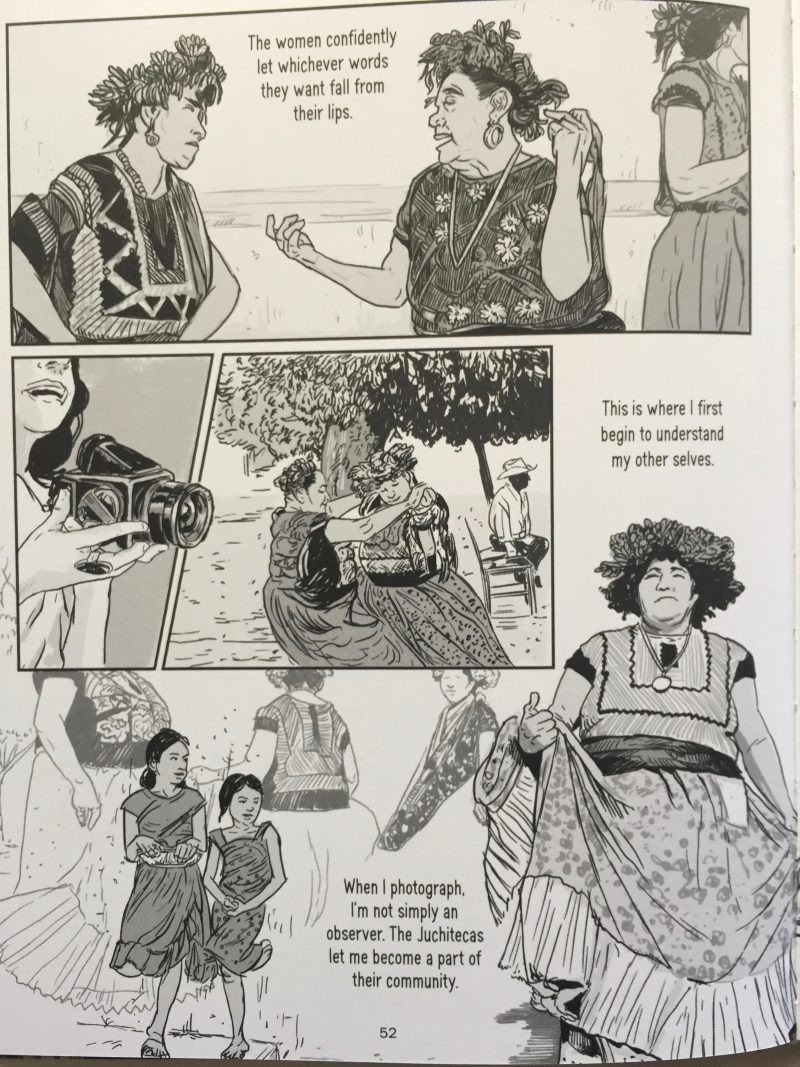

I have never seen a format such as this biography of the major, Mexican photographer, Graciela Iturbide. It is part graphic non-fiction; but it is also illustrated with Iturbe’s own photographs and was produced with her cooperation. I suspect it was intended for young readers, but nothing of its language speaks down to them, and given the adult interest in graphic narrative and the ongoing interest in reclaiming women’s histories, it will likely find a much broader interest – and it should. The illustrations intentionally cite much of the photographer’s own work, so that together with the actual examples it gives a reasonable survey of her subjects and approach.

Iturbide (b. 1942) belongs to a generation of Mexican artists that have received relatively little attention North of the border, although the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, presented a large survey of Iturbide’s work earlier this year – the first in the East Coast. The book begins with her decision to reject the domestic life her well-to-do family expected and become a photographer. It explores her two major mentors: the photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo and the Zapotec painter, sculptor and printmaker, Francesco Toledo. While Iturbide is best known for her photographs of indigenous peoples and country landscapes, she insists on a contemporary point of view, exemplified by her image of a traditionally-dressed, Seri woman walking through the desert carrying a transistor radio.