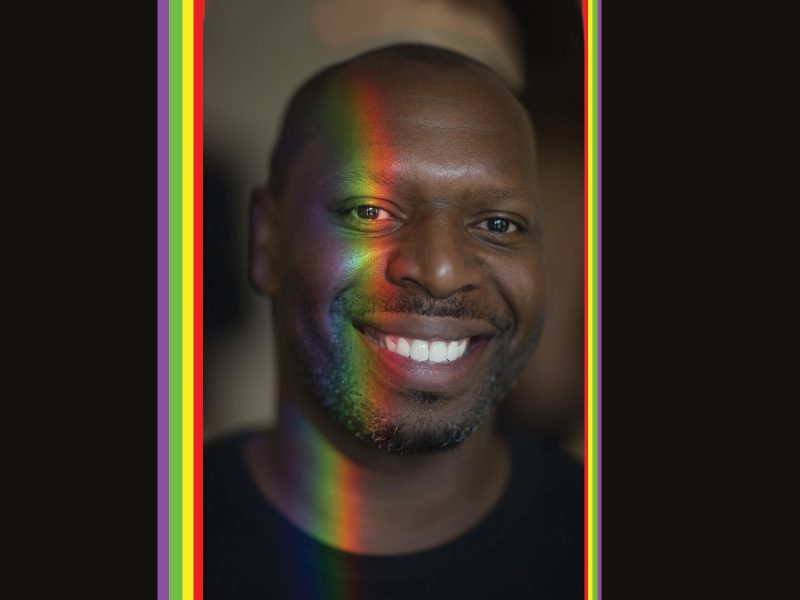

In this 27-minute episode of Artblog Radio, Wit has a conversation with multidisciplinary artist Rashaad Newsome about his creative experience “Black Magic,” which is currently in residence in Philadelphia at the Crane Arts Building. Rashaad shares how he builds multidimensional collages and assemblage, and how these pieces connect to the experience of queerness and the African diaspora. The work explores the importance of vogue and ballroom in the Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ communities, while also weaving together cultural iconography from throughout Black American and West/Central African art and performance.

Thank you to Philadelphia Photo Arts Center for allowing Artblog to record this podcast in their gallery.

Wit López: Hello and welcome to another episode of Artblog radio. I’m your host for today Wit Lopez. I’m super excited to be sitting in the gallery at Philadelphia Photo Arts Center with Rashaad Newsome, who has a really amazing show that’s here in the gallery, but it’s also a three part, uh, art experience.

Um, this beautiful show is called To Be Real, and it includes really amazing collages as well as sculpture. So welcome to the show, Rashad,

Rashaad Newsome: Thanks for having me.

Wit López: Oh, thank you. This is really beautiful. Thank you for bringing your work to Philadelphia. So, can you tell us a little bit more about, uh what you put in this gallery?

Rashaad Newsome: So, um, to be real is the exhibition component of Black Magic. And in a lot of ways, it’s sort of an amalgamation of a lot of ideas I’ve been thinking through over the past… Well, really- yeah, I would say decade. And, um, a lot of the works in the show are really centered around, uh, sort of the importance of…the imagination as a way for, um, marginal people to kind of, sort of free themselves from subjugation. You know, just kind of thinking a lot about, uh, how oftentimes we have these frames that are projected on us, um, particularly as black people and as queer people, and how we’re always trying to sort of expand or escape that frame that’s put on us. That’s sort of why the frames are very prominent in the exhibition because there’s sort of a visual representation of that.

And so every work in the show is engaged in its own form of resistance to either escape, um, or expand the frame. The one work that has made it out of the frame, um, would be “Ansister” the sculpture here on the floor.

Wit López: Which is absolutely gorgeous.

Rashaad Newsome: Thank you. Um, and so, and then sort of like the anchor of the exhibition is “Being” the first generation of my art, uh, LACMA art and technology prize project and “Being” for me represents, um. Really being free being has not only escaped the frame, but they, because they are an AI, they exist in completely in the realm of the imagination. And so they can be anywhere at any time and they can be anything. And so, uh,

Wit López: wow.

Rashaad Newsome: That’s sort of what I was thinking about for this show.

Wit López: That is amazing. Mind is blown. I really love it. Like this is, it’s gorgeous. So I also noticed that a couple of the frames have chains on them as well. Um, and I mean, from like a jewelry perspective, the chain shapes are also like jewelry chain shapes.

Um, they’re very common chains that are used within like jewelry making. But do they represent anything else or do they represent anything at all?

Rashaad Newsome:Yeah, they do. Um, when I first started my collage work, it kind of came out of me looking at heraldry, um, which is, you know, essentially an image made of images that represent rank, position and status within popular culture.

And initially I was thinking about, so like, what would be the images that represent this distorted notion of power today? And I was looking at sort of like, you know, as being from New Orleans, like bling culture, you know, kind of looking at advertising and popular culture and pulling images that sort of participate in the culture of domination that teaches us that we need things to have value. And kind of using those images to construct pictures that, um, critique the culture of domination.

And so very early on, rather than drawing a line, I was using images to create a line. And so the chain became my kind of mark making tool, which eventually, you know. entered the frames and into the videos and everything else. So it’s like a, an image that I go back to, but I think also it’s an elaborate allegory about, um, sort of how sometimes we can be caught in a paradigm where we feel that we need, these things have value. But if you’re in a position where in an inequitable society, you don’t have the same position to acquire those things so you’re kind of caught in this paradigm of constantly trying to get something that you can’t have, which then means that you don’t have value if your value is based on that. And so the chains also represent that kind of like bondage and as a representation of how we need to constantly, you know, do the work to decolonize our minds.

Wit López: That’s real. That’s real. Wow. Yeah. I feel that. I feel that. Um, and for me, like I’m from Brooklyn, New York originally. And so bling culture is definitely also a huge part of just existing as a black person or as a Latinx person, as a queer person, in New York city. So this resonates a lot, a lot with me too. So I appreciate you having that as part of your work and also connecting it to blackness, queerness, uh, together.

So I also noticed in your work, it’s like this, iconography not just a bling, right? Like you have folks with fronts on their teeth, but then also you have African sculptures that look like West African or portions of West African sculptures collaged into your work as well. Um, are there reasons why you chose those specifically in your work?

Rashaad Newsome: In regards to the mouths with the grills? That’s something that I’ve been doing for a while and there’s several ways in which that came in. One is, um, I love the movie, uh, little shop of horrors.

Wit López: (laughter) Me too.

Rashaad Newsome: And so, you know, when I started to bring flowers in the work, (I’m so bummed I never got to see it when it was on Broadway). But like, um, so the mouth being in the bud of the flower honestly was inspired by Audrey. And so, but, um, so that’s just kind of like a fun reference, but at the, at the same time, it really is in the context of these, um floral pieces. They’re very much engaged in like the history of Dutch still life, which was a lot about, sort of the, um, about vanitas.

And you know, a lot of, you know, during that, when that kind of movement started, you know, there were a lot of painters, like the people who could get portraits painted where people who are very wealthy

Wit López: Who could afford it. Exactly.

Rashaad Newsome: And so what Dutch still life did is kind of like equalize, um. That whole idea because it was sort of about.. you know, the one thing that unifies poor people enrich people as the promise of death. And so a lot of that’s why you’re often depicting, um, flowers and fruits and like perishable things to kind of remind us of the promise of death. But for me, I’m kind of flipping that in this piece because the flowers in this work are not organic flowers. They’re all jeweled flowers. So they will never die. They will exist forever. And so those mouths that are in the flowers are really the mouths of, um, black queer people.

And for me, that whole kind of re-imagining of, you know, the promise of death is sort of thinking about, um, the promise of, of immortality. The voice that will never end, that’s always going to speak out against dehumanization.

Wit López: Wow. That’s a lot. I appreciate that though. Like I really do appreciate that. And even just the mention of the promise of death, um, but also like this promise of immortality is, that’s, that’s beautiful. That’s beautiful. Um, so you did mention a little shop of horrors, and so is there any commentary in this piece that we’re looking at about consumption?

Rashaad Newsome: Well, yeah. I mean, I think that runs through all of the work, just through the use of the imagery that constructs the picture. You know, it’s all images of, you know, consumable, um, things, which actually brings me back to your question about, you know, the use of the, um, the African sculptures that really came from me, you know, kind of thinking about, uh, how my work was always, uh, in conversation with surrealism and cubism and how we often understand that as being this kind of Western idea, when in fact, it really comes from-

Wit López: Yup…. it’s not!

Rashaad Newsome: you know, European artists going to Africa and looking at the sculptural practices of African people and applying that to the painting surface.

It was, you know, I was thinking, what does it mean for me to kind of reclaim those images and try to make something contemporary and new? And so I see, you know, this work right here really as sort of a, um, Neo-cubist work where, you know, because when you’re looking at a Cubist image, you’re looking at it from several vantage points at once on several different planes.

And so I photograph, um, different, um, dancers that I’ve work with. In the round and then kind of collage those images together to create this kind of Neo-cubist form.

Wit López: It’s amazing.

Rashaad Newsome:And then the face is cut from several different masks from Western central Africa

Wit López: No, It definitely is. I love it. I love it. It’s gorgeous. It’s absolutely amazing. And I also love how you added around the inside of the frame are these geometric 3D shapes around surrounding the image of the body and the masks. That’s really, that is gorgeous. That’s really amazing.

Rashaad Newsome: Those are references to Cubism. Like more formal references.

I’ve looked at, um, the painting Les Demoiselle D’Avignon and, um, mapped out the way those surfaces were treated. And then uh, rendered them in a 3D program and then had them printed and chromed. And so the whole mirrorized environment that the figure existence is also sort of a way to kind of, uh, implicate the viewer.

So like, you know, I was thinking a lot about how, like the problems of trying to make counter-hegemonic work in hegemonic spaces. And so the limitations of that, and so by, you know, sort of implicating the viewer, you know, this, this whole effort to try to make this work that is trying to free itself, right? But it’s still existing within a certain paradigm being the gallery. Right? And so by having the viewer… be there.. You know, it kind of implicates the viewer on the ways in which they are participating in this figure… Um, not being able to be free.

You know, the, the piece is called “It Do Take Nerve” from the line in Paris is Burning when the guy says, um, “Give him a round of applause because, with y’all vicious motherfuckers, it do take nerve.”

So it do take nerve to try to make transgressive work in hegemonic spaces.

Wit López: That’s Real. That’s real. No, I, I, I appreciate that so much and it’s true. It does take nerve. It does take nerve.

Rashaad Newsome: And shoutout to Jack Mizrahi who was just here, hosted my ball here.. and um, he made a song called “It Do Take Nerve.” So shout out to Jack. He was happy to see this piece.

Wit López: That’s amazing. That’s amazing. Um, so you mentioned like freedom and not being free as like two themes kind of that are embodied within this piece that we’re sitting right next to.

And so with the piece that’s on the floor, the sculpture that you said had the opportunity to escape, to actually escape from the work and just to be, right. You mentioned it was called “To Be,” right?

Rashaad Newsome: Well, the sculpture is called “Ansister” and the AI is called “Being.”

Wit López: Okay. Okay. Gotcha, gotcha. Okay, so sorry, I mixed that up. Apologies. Um, but that piece on the floor, can you talk a little bit more about the freedom that it’s experiencing? And also I noticed that it’s doing a dip (laughter) very amazingly, and I love that it’s doing it, but also kind of frozen in time since it’s a sculpture.

Rashaad Newsome: Yeah, I, with that piece, I was really thinking about how to kind of, you know, that whole idea of expanding or escaping the frame. And for me, I wanted the figures that exist in my work to actually escape the frame and be in the space and the three-dimensional, um, way. And so, uh. When I started to think about that, you know, like those figures in the work are usually a synthesis of, you know, African sculptures, but then also the bodies of, um, women who work in the urban model industry.

And so, um, I was thinking, how could I render that three-dimensionally and also have it be, uh, you know, a form of collage where I’m working with things that exist in the world.

Wit López: Amazing.

Rashaad Newsome: And so, um, you know, to kind of have, that wood veneer kind of hit against, you know, like a flesh-like material. And so I started with the bust and I, um, went to Ghana to do research for the show. And I had a master Carver carve that bust, and it’s based on the female full mass of the, um, Chokwe people of the Congo. And that mass kind of represents, um-and we, it’s, it’s a matriarchal society. And so I was thinking about, you know, like, agency around marginal bodies and how that, you know, how could I incorporate that conversation into the figure, um, particularly within the diaspora- and so the top part kind of represents that conversation.

But then when I was thinking originally like, Oh, I needed to have the like, flesh like legs, and how could I, you know get something in the world that already exists to do that. And so I thought, Oh, the sex doll, it was really kind of practical solution to have that kind of skin like material and neat wood. But the odd thing about it is that when I bought the sex doll, when I got it, the skin for the black sex doll looked a bit weird. It was kind of…

Wit López: Ashy? (laughter)

Rashaad Newsome: Ashy….. gray. (laughter) It wasn’t really black, it wasn’t really Brown.

Wit López: Always… always… (laughter)

Rashaad Newsome: So they hadn’t really perfected that. So. Um, but the great thing about is that, you know, it’s still allowed the work to kind of exist in like collage. So it’s much more assemble assemblage, which is kind of analogous to collage. And so rather than show the flesh, I kind of put tights on it.But the great thing about it was it allowed me to kind of create that perfect dip form.

And, um, and then the, the dress that it’s wearing was a a kente that I acquired in um, the… Bonyere region of Ghana, and it’s a vintage kente that tells the story of colonialism So I had dress kind of made of that material and then stoned it as kind of like, to kind of make references to kind of like drag and like queer culture, which is also a part of the conversation.

So, yeah, it’s, um, they represent the ability to actually escape the frame and the pose of them being in a dip. It’s kind of like in this kind of pose where they kind of, it’s kind of bringing the figure down to the ground and grounding themselves, right? And caught into like a certain, um, form of ecstasy.

Wit López: Yeah. I love that. That’s amazing. So I also noticed that you have them in a pair of Red Bottoms or Louboutin, which is a type of shoe that looks like a, that people tend to really like and really enjoy, um, or kind of uphold amongst shoes. Like they’re treasured amongst all heels. Is there a reason why you chose red bottoms?

Rashaad Newsome: Yeah, I mean, I, I thought, you know, like I was thinking, I had done a collaboration with Louboutin, um, for the Killer Heels exhibition at the Brooklyn museum? And so, you know, during the time I worked on that project, part of the reason I chose to collaborate with them- besides the fact that it was an exhibition around, you know, women’s shoes and like that, uh, the effects, you know, and how that affects popular culture- I was thinking about, um, again, you know, like images that sort of participate in the culture of domination and how these shoes have become emerged as this object that, you know, you know, particularly black folk, really coveted. And they really had something that was like really important. It was like a status symbol.

Wit López: That’s real, yeah.

Rashaad Newsome: And so, um, in the context of that video, I was kind of… it became so absurd the way in which they were used as a way to kind of comment on the whole notion that you need to have those have value. But I wanted to kind of bring that back into the work. You know, again, kind of. That conversation about the culture of domination and sort of how like the figure is grounded, but this shoe is sort of-

Wit López: Elevated.

Rashaad Newsome: Held up, yeah.

Wit López: (laughter) That’s amazing. That’s amazing. Um, I, I really love it. Like it’s a, it’s a brilliant, brilliant piece and I also love that you went directly to the continent to source these things for the imagery of the piece. Um, eve, I definitely recognize like the weave in the fabric and I was like, Oh, that’s a real, that’s a real one.

Because a lot of, a lot of kente fabric that we have here in the States, and that exists kind of within like Western, Westernized spaces, um, it’s not woven anymore. Like a lot of times it’s just printed directly onto the fabric. So to see like actual weave, like that’s, that’s really amazing, you, that’s beautiful. Like I really love it.

Rashaad Newsome: Thank you. I would, for that, I was really thinking about too, like. Um, what does, you know, like luxury, look like within the diaspora because I had been playing with like consumer things and so often our ideas as African Americans around luxury come from things outside of ourselves.

Wit López: Yes.

Rashaad Newsome: I was really trying to speak to that in that work over there as well. Um, “Acosia” because, you know, she has this very like, elaborate hairstyle and I was thinking about, you know, um. The Bronner Brothers Hair Show and the legacy of that show and which is a synonymous with like really kind of, um, luxurious and elaborate hairstyles.

And then I was for “Ansister”when I was thinking about the dress like, well, when you think about couture or within a diasporic space, it’s kente, it’s artisinal, it’s made by black folk and the continent. And so it was really important that the dress be made out of that material. I kind of wish it was used a lot more, and hopefully in modeling how this can be seen as a luxurious fabric for those who don’t see it that way, hopefully it will. Inspire.

Wit López: No, that’s real. That’s real. Um, I mean, trying to acquire it, like trying to acquire authentic fabric from the continent, like here? Can definitely be very expensive. So it’s like a lot of the prints that you see here tend to be on, like tend to not cost as much as the actual fabric does when you try to get it shipped here. So it’s definitely a luxury item, but I don’t think enough people..

Rashaad Newsome: You got to know folk, you know, cause everybody, somebody’s always going home and then when they come back, you just tell them yo bring you a piece, yeah! (laughter) You know how we do, yeah.

Wit López: (laughter) Exactly. Bring me some Shea butter, too!

Rashaad Newsome: Yeah. You know, it’s Shea… kente…. all of that. You just gotta put your order in. That’s why black people be having all those bags when they come back. They’re bringing stuff back for everybody. (laughter)

Wit López: You know what someone actually taught me once? They were like, no, what you gotta do is you have to mail it back home so that way it gets there by the time that you get there too.

Rashaad Newsome: Yeah. The mailing can be a little tricky too, so it’s always good when you can, like if you know somebody who’s going. And they can put them in, bring it back for you. Cause then you never know if you actually gunna…. get it..

Wit López: See it in the mail? Right.

Rashaad Newsome: Yeah. That’s a whole other problem going on there.

Wit López: That’s real. That’s real. Um, so can you talk a little bit about the ball that was had here on Saturday, right?

Rashaad Newsome: Yeah. The ball. Um, it’s again, kind of engaging in that whole conversation around the imagination as a form of, um. Resistance. And, um, in that, in that particular project, I was thinking about how oftentimes in ballroom, um, there is, the frame that’s projected on, on folk participating is sort of- ironically- binary forms of gender, like Butch queen, femme queen and stuff like that.

And like, you know. It’s kind of strange because we’re in like this queer space, which should, which it, which- not even should- it does have room for all types of, you know, genders and gender presentations. Yet somehow there’s still a mirroring of, um, heteronormative kind of like systems or ideas of gender.

But then there’s also this kind of, um. Allegiance to capitalism too, with like labels, like, uh, categories like labels and stuff like that. And so much about what you can acquire. So like the culture of domination shows up again. And so with the ball, what I’m trying to do with that frame is completely obliterate it and put a premium on creativity.

So what does it mean for, um, someone to walk and re-imagine, you know a McLean painting on the ballroom floor, or a Marlon Riggs segment and a video on ballroom floor, or Bill T. Jones piece. So it’s really kind of asking people to, you know, use their imagination as a way rather than what you can have.And hopefully that idea will kind of continue, um, outside of ballroom.

Wit López: That’s real. That’s real. Wow. I never thought about that, but the idea of like how can you recreate a painting or a photo or an object. On the floor. That’s amazing. That sounds really great. I’m sad that I missed it. Next time, wherever there’s another one, I’m going to be there.

Rashaad Newsome: In Miami, December 4th.

Wit López: Hey, listen, if I got to get on that plane, I’m gonna be on that plane. (laughter)

Rashaad Newsome: It’s going to be the Titans ball.

Wit López: Oh my goodness.

Rashaad Newsome: Best of the best. It’s the battles that you never get to see, that you want to see.

Wit López: It sounds amazing. Ugh, I can’t wait. I can’t wait. It’s super exciting. Um, so what else do you have on the timeline besides this Titans ball that you mentioned in December 4th? Do you have any other shows that are accompanying this exhibition?

Rashaad Newsome: Well, coming up on Saturday, I’ll be doing, um, the third part of this project, which is my performance FIVE. Um, and I’m working with, um. A group of New York based, um, performers and Philadelphia as well as New York and Philadelphia based musicians.

And, um, in that piece, uh, the frame kind of re-emerges again, um, a big part of that piece is about kind of like the diasporic tradition of improvisation. And so I, um, I have this, um. Custom made motion tracking technology that I use in the performance that’s also a form of collage because it’s creative coding and different, um, video game hardware.

And during the live performance, um, there’s sort of a frame on the floor in which the dancer performs one of the five elements of Vogue family. And as they perform the dancer, I mean the musicians and the vocalists and I all imbue them with, you know, improvisational energy. We’re all just kind of playing like sort of a jazz trio.

And as they are charged with this energy, um, I’m motion track their movements and you see this form being generated on the screen above them that has kind of escaped the frame as a way to kind of talk again about kind of escaping the frame.

Wit López: That is brilliant. And it, Oh my God. Oh, the way your mind works is like brilliant. That is amazing. To create something that’s so multilayered, multidimensional, but like very representational of the collage of black culture, of queer culture, of ball culture. Thank you. Thank you. Like that… I am in the presence of greatness. (laughter) This is amazing. Oh my goodness. Wow. This is, and

Rashaad Newsome: I would say, I would say that’s coming up is, um, you know, so that performance will complete the sort of East coast, uh, presentation. But then the whole project is going to travel to the Bay area, to Fort Mason. Center for art and culture. So we’ll stage the exhibition again and um, there’ll be a performance, but this time it will be my performance “Running,” which is all about the kind of diasporic tradition of like vocal runs as well as, um, another ball.

Wit López: That’s amazing. Oh, that is so exciting. (laughter) That’s really cool. And it definitely is a diasporic, uh, vocal tradition. Yeah. And it takes so many different shapes throughout the diaspora, and so many different parts of it are valued depending on where you are and what you do. Like there’s some things that are only valued in church that are not as valued outside of Black church.

Um, but yeah, that, that sounds amazing. I might have to hop on a plane to the Bay too,

Rashaad Newsome: Yes, come on!

Wit López: Oh my goodness. Well, thank you so much. This has really been, this has been an amazing, uh, interview. Thank you for your time. Thank you for your energy. Thank you for your talent and for sharing it with the Philadelphia community.

It’s very, very appreciated. Um, for, you know, putting blackness and queerness on display in this really respectful and, uh, just kinda feels like a, it’s an honor. Thank you. Like, I, as a black queer person, I appreciate this. I really, really do. Um.

Rashaad Newsome: That means a lot to me.

Wit López: It means a lot to me! Like, this is beautiful. This is beautiful. Um, and it’s not a mockery, you know, which, which unfortunately happens way too much, I feel like. So thank you. Um, thank you for real. I really appreciate it. Um, but also, thank you for your time today. I’m deeply appreciative of this. Um, and I look forward to seeing more of your work in the future.

And I’m telling you, if I have to get on a plane to the Bay, I will! Come see your work. Oh, it’s exciting. It’s exciting. So thank you, and thank you to those of you who are listening.

If you want to listen to this, you can listen to it on Artblog’s website, on Apple podcasts, or on Spotify.

Thanks so much for tuning in and have a wonderful day. Bye y’all.

You can listen to Artblog Radio on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. HUGE Shoutout to Kyle McKay for our original Artblog Radio intro and outro.