When attending a conference in Taiwan in November 2018 I saw a large exhibition of pan-Pacific indigenous art – part of the Pulima Art Festival in Taipei– and indigenous artists featured prominently in the 2018 Taiwan Biennial at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiching. This shamed me into realizing how little I knew of contemporary Native American art, an ignorance that obviously extends beyond the personal. Institutions such as the National Museum of the American Indian obviously cover this territory and I have benefited from its exhibitions of contemporary artists, one of which I reviewed.

There have been a few, small signs of progress in mainstream museums: a group exhibition at the Whitney, “Pacha Llaqta Wasichay,” that dealt with the legacy of the Indigenous cultures of South America on Latinex artists – although it did not make clear whether the artists were themselves of Indigenous background, Jeffrey Gibson‘s work at the New Museum, Kent Monkman currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists” opening at the Renwick Gallery on Feb. 21.

The following books offer recent scholarship on Indigenous art.

Philip J. Deloria, “Becoming Mary Sully; Toward an American Indian abstract” (Seattle, University of Washington Press: 2019) ISBN 978-0-295-74504-6

The historian Philip Deloria inherited a fascinating and complex body of artwork and with it, an art historical puzzle. What did the work mean, and how does this entirely unknown group of drawings fit within the art of its period? It was the lifelong project of his great aunt, Susan Deloria: 134 works on paper – each in the same format of three, stacked images on paper of varying sizes. Making her art under the name of Mary Sully, she called the triptychs “Personality Prints”; they are predominantly abstract and are drawings, not prints, executed with colored pencils and occasional highlights of gouache. Most of them represent celebrities from the worlds of sports, entertainment, popular culture and politics, including Amelia Earhart, Thomas Edison, Fred Astair and Shirley Temple, as well as public figures, hardly famous, who had an influence on the artist’s life. A handful represent concepts rather than people, and two of these are central to Deloria’s research: “Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present,” and “The Indian Church.”

Susan Deloria/ Mary Sully (1896-1964) was Dakota Sioux on the paternal side, but no unitary marker of identity could characterize her. Of mixed blood, born on an Indian reservation and the daughter of a minister of the Sioux Episcopal Church, she was peripatetic and lived in numerous places both on and off reservations. These were urban as well as rural, including extended stints in New York City, and while her formal art education was slight, she lived with a sister who worked with the leading anthropologists of the day and was involved in forefront research on personality and culture. As to Mary Sully’s intent – beyond her titles, all we know is that she hoped her work would be widely exhibited – which inherently meant exposure beyond the Native American community – and would sell, producing income. In this she failed entirely.

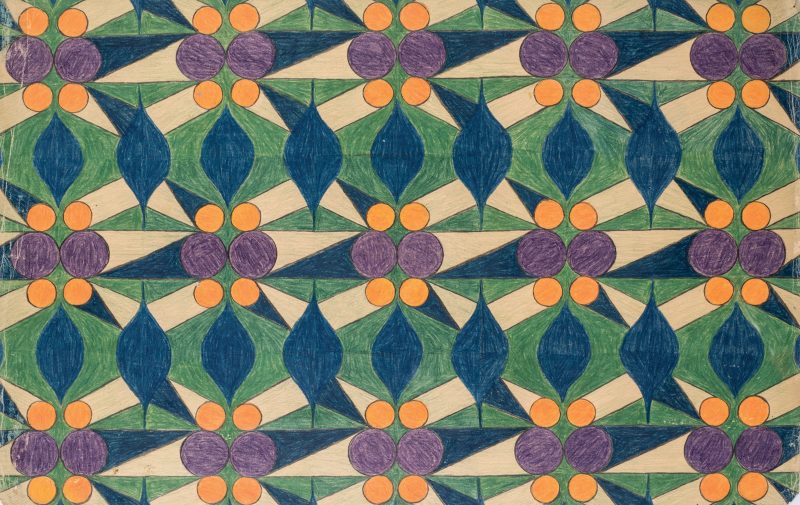

The format of the Personality Prints has no obvious precedent. Many of Mary Sully’s designs are visually striking and play with figure/ground relationships and images that shift between double readings (of the two profiles or a candlestick? variety). The top sheets were created on the largest scale and sometimes portray recognizable scenes such as landscapes, individuals and crowds. The upper and lower drawings are bi-laterally symmetric, which distinguishes them significantly from Western Modernist abstraction. Colors, imagery and shapes from the top sheet are modified in the two below it. The middle sheets are primarily repeat patterns of geometric character – often highly detailed. The images bleed to the margins of both the upper and middle sheets, giving the latter a formal resemblance to fabric or wallpaper patterns. The lowest sheets are on an intermediate scale; they adapt forms from the sheet above and have borders, sometimes patterned, so that they assume the format of Native American or Middle Eastern carpets.

It is clear that every aspect of Mary Sully’s work had meaning, and Deloria is systematic about teasing out what he can. He examines her family and personal histories and the place of Native Americans within the larger national history. He looks at the art of Mary Sully’s Modernist contemporaries; in the 1920s abstract portraits became something of a fashion among artists of the circle around Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and early dealer of modernist art. It is plausible, but by no means certain that the artist saw any of these, and notable that Sully’s celebrities included writers, musicians and actors but no visual artists. Deloria investigates Native American visual traditions that Mary Sully would have known. He studies her knowledge of forefront discussions about psychology, personality and how they function within cultural groups. I suspect that Sully may have learned some of her visual language and ideas about Modernist art via its absorption in popular art forms such as magazine, book illustrations and comics. Comic artists of the 30s such as Frank King and George Herriman employed the sort of visual illusions that Sully used and their work contains explicit references to Modernist art and art history. In the end it is Deloria’s insight that positions Sully’s work as a nexus of Modernist and Native American visual art.

In his introduction Deloria asks:

“How do we make sense of a body of work by a Native artist that seems so radically out of the received traditions of American Indian art of the mid-twentieth century– and so much not a part of the received traditions of modernism, even at their most capacious? In what ways might this art change our understanding of both Native arts and American modernism itself?”

“Becoming Mary Sully” introduces the stunning and original work of a heretofore unknown artist. It also establishes one model for approaching other bodies of work that were isolated or kept apart from the mainstream art world, such as Hilda Auf Klimt’s abstract, spiritual paintings, Henry Darger’s personal narratives, and possibly even entirely anonymous work, such as that of the Philadelphia Wireman. How we weave them into the history of art will be up to us.

Part 2 continues the look at recent writing on Indigenous art.